It is supposed to be one of the happiest times of family life as you get ready to welcome a new baby.

But for some, pregnancy and birth can bring heart-breaking depression, mental illness and, in some cases, suicide.

Now The Courier has launched a special investigation into perinatal depression – which is depression defined as striking during pregnancy or in the first year after birth.

We heard deeply upsetting stories from mums and dads from across Tayside, Fife and across Scotland caught in this position, including one family who lost their daughter 10 years ago and who say little has changed in that time.

Campaigners also say that for too long Scotland has offered patchy and overstretched services especially for those who live away from the central belt with women in Aberdeen and the north of Scotland facing huge journeys to get the help they need.

We also discover how dads can also suffer from severe perinatal depression but are often overlooked by our health care system.

The Scottish Government have vowed to act. They have already given a £50 million cash injection to boost mental health services for families while working with health boards across the country to develop community perinatal mental health care.

Rosey Adams faced the double stigma of being a teenage mum and suffering the torment of perinatal depression.

The Perth mum grappled with dark thoughts, even considering ending her own life to escape her daily psychological battles.

Now she has transformed her life by becoming a maternal mental health campaigner fighting to help struggling mums facing the challenges of the pandemic.

The 31-year-old mum of three is now an ambassador for perinatal mental services in Tayside.

I was going through the motions but I wasn’t mentally there, I felt lonely and angry, angry at the whole situation and wanted to know why this was happening to me.

She said: “The postnatal depression I had with my daughter was the worst because I did not know what it was.

“In the first six weeks, it was especially bad. That time was really quite dark. I didn’t feel I bonded well with her, in fact I would make excuses not to be with her.

“It took me until she was about nine months old to actually go and get help from my GP. I was 19 when I had her and there was also that stigma about being a young mum.”

‘It’s so important to know that it does get better’

Rosey brought up three small children on a remote Scottish island before she moved to Perth. She said: “I was put on medication but wasn’t really given anything else due to where I was at the time and the postcode lottery of perinatal mental health.

“With my second child, it took a while for the postnatal depression to come along but I had the dark thoughts, not wanting to be around anyone and feeling really disconnected

“I had my third child and that was probably my worst experience of antenatal depression. I felt really suicidal during that pregnancy. I was only ever offered counselling and medication.

“Peer support is really beneficial because it can bridge the gap if you don’t have access to specialist care, you can speak to someone who has been there, done that and bought the t-shirt and give you the hope you need.

“It’s so important for someone to know that it does get better. You won’t always feel as low and disconnected. If you are having problems bonding with your baby, it changes and does get better – it is why I am so passionate about peer support and perinatal mental health care in general.”

‘Postcode lottery of care across Scotland’

Rosey set up her online perinatal mental health support group when she moved from Lewis to Perth four years ago to fill the gap in services.

She now runs her PND Hour on Twitter every Wednesday from 8 to 9pm where expectant mums can discuss their anxieties and experiences.

She added: “Perinatal depression is a two generational illness as it can affect the baby. It’s about making sure the mum knows that she and the baby will be okay with the right support. It has to be the whole family unit you look after.

“I was disconnected, like looking at myself through a one way mirror. I was going through the motions but I wasn’t mentally there, I felt lonely and angry, angry at the whole situation and wanted to know why this was happening to me.

“It’s such a postcode lottery of care across Scotland. There are areas that are doing fantastic work and have well established perinatal mental health teams but then you have the pockets of areas that families don’t have the support they need.

“If you think of the Highlands and islands, especially the islands, that’s where I had my kids, that remoteness and isolation you feel is multiplied with the current pandemic as you don’t have access to the same support so you feel even more isolated and makes it even harder to reach out and ask for the help you need.”

Rosey has amassed more than 17,000 followers keen to get the benefit of her wisdom which she says has made her an “expert by experience”.

In one of her tweets, Rosey emphasises the importance of trying to seek help. She wrote: “If we don’t look after the maternal mental health of our pregnant and new mothers, I believe there will be an increase in maternal deaths due to the unimaginable stress they are going through.

“Please reach out. You are not alone.”

Scotland only has two mother and baby mental health units – with just 12 beds in St John’s Hospital in Livingston and the West of Scotland Mother and Baby Unit in Glasgow.

One mum faced a 350-mile round trip to get help. Lesley-Anne McDonald, 37, from Inverallochy, Aberdeenshire, lost five litres of blood and had signs of severe postnatal depression and anxiety when her daughter Lily-Anne was born five years ago.

She said: “I feel for mothers going through this during the pandemic. It is really sad there is this postcode lottery where the level of care depends on where you live.

“There is such a limited capacity. I was lucky to get the help I needed. It was a dark and scary time and I was shocked to hear that I would need to go to Livingston, hours away.

“My partner had to work so I would only see him at weekends. I feel it stole that first few months of her life. For me, unfortunately, it was so overwhelming and debilitating – I had to go to the mother and baby unit – because I was just so unwell.”

Along with her daughter Lily-Anne, she was admitted to the specialist mother and baby unit in Livingston.

‘You feel like you are actually going mad’

She said: “It’s so lonely and isolating. You feel like you’re actually going mad. That’s how I would describe it. The anxiety was so intense that I felt like I was losing my mind – it was really quite scary.

“I had to leave my partner to go down there. That was stressful in itself – without the illness and not being sure how things were going to go. It was really worrying.

“I feel it stole that first few months of her life.”

The Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland has called for better community treatment – and said huge areas such as Grampian, Fife, the Highlands and the Borders – still do not have a perinatal mental health service despite years of campaigning.

Here Dr Selena Gleadow Ware, chairwoman of the perinatal faculty at the Royal College of Psychiatrists in Scotland, discusses:

- The impact the Covid pandemic has had on new parents and families.

- Treatment for perinatal depression

- Stigma around mental health issues for mums and dads

She harked back to the days of ancient Greece to help struggling mums facing the abysmal ‘postcode lottery’ of lifesaving maternal mental health support plaguing Scotland.

Aberdeen mum Louise Dredge gave up her job as a primary school teacher to retrain to help new mums and dads.

She was horrified that many mums – especially in the north of Scotland – face travelling hundreds of miles to get access to a handful of beds at just two specialist mother and baby units.

Crusading Louise became a “doula” – a professional trained to provide emotional and physical support to women throughout pregnancy, birth and the early postpartum period.

Louise said the patchy nature of services for mums and dads added to the severe psychological strains of lockdown meant that the system was now at breaking point.

It can be a really difficult transition to go from that controlled work environment to then becoming a parent where you actually have to let go of a lot of control.”

Mum of two Louise, 34, said: “I’ve been up and running since last August. There has been a lot of anxiety that has been rising through the possibility of birthing alone, and not being able to access a lot of the services that new parents rely on.

“I had some antenatal anxiety in terms of monitoring my daughter’s movements and things. When she was born, I found parenthood utterly overwhelming. There can be a big fear factor around birth.

“Although birth can have its challenges, it’s an event. Once it is over with, it is a one off but parenting and postnatal life is the rest of your life. Once you have a child you are a parent.”

‘I felt angry that I could not control things’

The word “doula” comes from ancient Greek meaning “a woman who serves”. Doulas can assist women with births at home or in the hospital by providing pain management techniques, reassurance and advocacy.

Louise added: “Nowadays, women can have careers and we are not stay at home people any more. A lot of women in their careers are in quite high powered positions, they have a lot of control.

“It can be a really difficult transition to go from that controlled work environment to then becoming a parent where you actually have to let go of a lot of control.

“I had a lot of postnatal rage – one of the symptoms that not a lot of people know about. I was feeling really angry that I could not control things. I felt a bit helpless.

“It became all consuming. My aggression became more about being angry with myself, some self harm, some suicidal thoughts, thinking my daughter would have been better off without me.

“A voice in your head telling you that you are not doing well enough. It affects every part of your life.”

Now Louise is keen to reduce the stigma around perinatal depression. She said: “I look after mums. The transition to parenthood can be an anxious and unsure time for many and so I give emotional, practical and informational support.

“Having had my own children – now 21 months and three years old – I know how hard pregnancy and parenting can be on some people.

“Having suffered from antenatal and postnatal depression and anxiety, it made me realise that there needs to be more support for those who experience this in Aberdeen.

“My services aim to prevent people from getting to breaking point as I want to make sure that women feel heard, empowered and supported.

“I have become passionate about talking about perinatal mental health, both from my own experiences but also in the hope that I can help to bring about the end of the stigma attached to it.

“My main aims for the future are to offer group in-person classes for my hypnobirthing and postnatal planning and preparation courses, and also to spread the word on what a postnatal doula is.”

Karen McAllister died 10 years ago but her presence fills the room.

Her images line the walls, staring down with her two beloved daughters, a silver K ornament sits next to the mantelpiece and her mum even wears Karen’s favourite Marks and Spencer perfume.

In 2011, Karen begged doctors to treat her at a psychiatric unit after she started feeling paranoid and hearing voices but was told to come back later when a bed was available.

Karen then went home and seriously injured herself. She was taken to hospital but died three days later at the age of just 26.

Her mum Carol even has Karen’s name inked on her wrist, every pulse a silent and unnecessary reminder of her lost daughter.

Carol, 60, said: “It is a pain that does not go away. You never stop thinking about Karen. We were determined to fight for her.”

‘For her to just be sent home when she was so ill is just unbelievable’

Carol says struggling new mums like Karen have been utterly failed by the maternal healthcare system – a ‘postcode lottery’ patchwork with large portions of the country left without specialist services.

Massive swathes of the country – including Grampian, Tayside, Fife, the Highlands and the Borders – still do not have a perinatal mental health unit despite years of campaigning.

Karen’s tragic case may be the tip of the iceberg with the pandemic triggering a burgeoning perinatal mental health crisis.

Things could be even worse now for mums that are struggling to cope.”

We discovered that in just three months of the pandemic, at least four mums ended their own life, according to a new report.

The Mothers and Babies: Reducing Risk Through Audits and Confidential Enquiries across the UK (MBRRACE-UK) survey found that 16 women across the UK died during the perinatal period between May and August last year.

- Four died by suicide

- Ten women died with Covid or Covid-related complications

- Two died from domestic violence.

- Seven of the women were from black and minority ethnic groups.

Carol has dedicated the last decade of her life to fighting for justice for Karen, recently winning the family’s medical negligence claim.

She revealed that support services have not improved – but potentially worsened – since Karen’s tragic death in 2011.

Carol, from Glasgow, said: “For her to just be sent home when she was so ill is just unbelievable. It was not right. Now, with the pandemic, people are really struggling with their mental health and you hear of suicides all the time. Things could be even worse now for mums that are struggling to cope.”

I keep thinking if they had taken her in when she was struggling, maybe she would be here now.”

Carol says Karen was failed by doctors at the Southern General Hospital in Glasgow in February 2011. After a 10-year battle, health chiefs agreed with the family and admitted negligence.

Full-time mum Karen turned up for an appointment at the Mother and Baby Mental Health Unit at 10am on February 16 pleading to be admitted but was told to come back at 6pm when a bed would be free.

She injured herself at around 5.50pm. Her partner found her in the bathroom and she was taken by ambulance to the Southern General but died from a blood clot.

Her daughters, now 10 and 12, have been brought up with only memories of their mother. Health chiefs said they had learned lessons from Carol’s tragic case but her family remain unconvinced that things have changed for depressed mums.

Carol said: “I keep thinking if they had taken her in when she was struggling, maybe she would be here now.

“If doctors turn you away when you are ill, what chance have you got? At the time, we were told the unit only has six beds and is supposed to cover the whole of Scotland. It’s a disgrace.

“We have to keep her memory alive. She loved those children so much and would never have wanted to leave them.”

Every year on the anniversary of Karen’s birthday on November 3, the family go to a nearby beauty spot to release balloons and put on a fireworks display in her memory.

They have even got a star named after Karen so that her daughters can look into the sky and be reminded of their mum.

‘We got justice for her’

Karen’s sister Jacqueline McAlister, 30, said: “She was my best friend, we did everything together. She was really funny, just hilarious.

“Karen was a really funny, caring person. There was one time she cut all her hair off. She had long hair but had chopped it off. It was dead out of character.

“When I look back now, it was a key point in what was going on with her. That was two weeks prior to her passing away.

“Karen’s youngest daughter is very sensitive and sometimes gets upset that she is not there. Seeing her daughters growing up is a constant reminder of her but she would never be forgotten.

“I feel happy that they have admitted negligence but it’s a cheek for them to have been making us fight for so long. It’s not going to bring her back but her daughters will know she should have been helped and we got justice for her. Her girls will know she should have got help.”

Karen’s auntie Alison, 54, from Pollok, said services needed to be improved across the whole of Scotland to stop another devastating tragedy.

She said: “Karen was my best friend. In my house every weekend. She would do our nails, do the tan then go to the dancing.

“The last time I saw her she had cut off her hair. We had been arranging a surprise birthday party for my mum and then when I phoned my mum she said Karen was going to Alloa.

If this can happen to Karen, it can happen to anyone. Doctors at the hospital should have taken this seriously rather than ignoring it.”

“I said she couldn’t do that as we had arranged a special night. Karen came on the phone and she said she was going there to sort her head out.

“That was totally out of character. I told her I loved her and that was the last time I spoke to her. I was out looking for her when she went missing from the hospital.

“My house is like a shrine to her. I wear her perfume as well. She will never leave us, never. She was let down big time.

“It is just disgusting. I am pleased that they can look back and read all the paperwork and everything that we tried to do to fight for their mum.

“It is the end of an era now. In a way it is sad, when you are fighting for her, you are keeping her alive. Now, what do we do?

“If this can happen to Karen, it can happen to anyone. Doctors at the hospital should have taken this seriously rather than ignoring it.”

An NHS Greater Glasgow & Clyde spokesman said: “We would like to reiterate our sincere condolences to the family of Ms McAllister following her death in 2011.

“We recognise the family’s loss and the grief they have suffered, and we would like to apologise for that. We would like to assure the family that the organisation has learned from these tragic circumstances.”

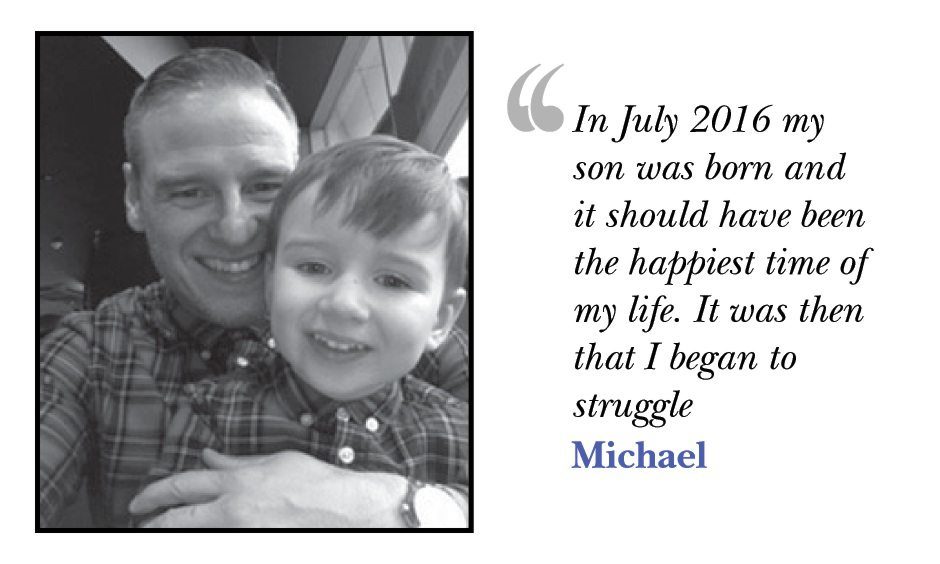

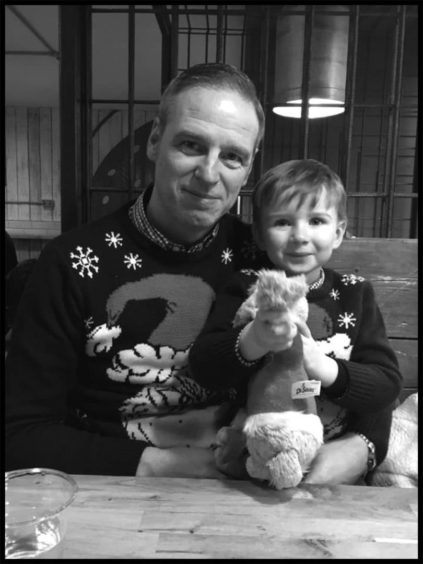

Michael was a high powered executive commanding a major organisation with millions of pounds in its budget. He should have had the world at his feet.

But he knew something was wrong when he was working more than 14 hours a day just to avoid seeing his newborn son.

Michael Byrne went from being a housing director and a new dad to teetering on the precipice of ending his life.

He nearly became part of an invisible epidemic across Scotland – one of a growing number of dads suffering perinatal depression, a condition largely overlooked by the mental health profession.

Our probe found that at a time of already terrifyingly high levels of male suicide in Scotland, there is growing concern about the severe lack of mental health services for new dads, dads-to-be and partners.

We discovered that despite the horrors of the pandemic, funding for dad-specific support has been cut.

Fathers Network Scotland have called for urgent action to stem the tide including: starting to record the number of deaths by suicide of partners during the perinatal period. Currently only mothers are recorded.

The group also wants partners’ GPs informed about the birth of a baby as currently only mothers’ GPs are notified.

Survey: More than two thirds of Scottish dads say their mental health deteriorated during second lockdown

They want better funding for men’s mental health support and suicide prevention and training for service-providers such as health visitors and midwives to recognise and ask about poor mental health in male partners as well as mums.

Michael – who says the paternal mental health care system is a “disgrace” – is a warrior lightly bearing the invisible scars of his life.

The 51-year-old said: “I have a chequered history of trauma. I was a three-year-old boy when I first witnessed violence by both my parents.

“I grew up with the narrative that ‘no-one loves you’ and ‘you will never be good enough’. It was a tough upbringing in the Gorbals and Castlemilk but there were other things such as seeing my mother stabbing my father in the head.

“I also saw him being hospitalised after she hit him in the head with a cooking pan. I also had an inability to talk about these things.

“I thought it was normal. Then my father was murdered when I was in my 20s. It happened on a Thursday night and I got up and went to work on the Friday.”

I was terrified to be with him in case I lost my temper. My wife had a difficult pregnancy and yet all the dads at one point were asked to leave the ward.”

He later suffered further mind-bending trauma when he lost twins to miscarriage, underwent a painful divorce and survived the Clutha disaster.

He said: “In July 2016 my son was born and it should have been the happiest time of my life. It was then that I began to struggle.

“I was terrified to be with him in case I lost my temper. My wife had a difficult pregnancy and yet all the dads at one point were asked to leave the ward.

“It was just the way they did things. I felt completely unsupported as a man, there was no thought given to how the dads were getting along.

“It was all geared towards the mum. I started to work excessively, that was my way of dealing with things. I would leave before 7am and not be home until well after 8pm.”

Raising awareness

Around one in ten new dads suffer from postnatal depression with up to 45 percent of dads affected by postnatal stress and anxiety.

Experts agree that if a dad’s mental health is not recognised and supported during the perinatal period, then his ability to engage supportively both as a father and as a partner may be at risk, limiting positive outcomes for his child, partner and family.

Michael’s experiences at the Clutha bar in Glasgow cast a long shadow, leading partially to a diagnosis of Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

After the helicopter crash, Michael and his pal Tam Foulis helped lift part of the bar off two customers trapped underneath, then escorted other survivors to safety.

He said: “The things I saw that night were horrendous. In the first few seconds, everything was incredibly quiet. It was like a snow globe, with all the dust falling. We ran around to the other side of the bar. That’s where the real devastation was.”

Dr Sigi Joseph of the Royal College of General Practitioners said: “The bringing home of a new dependent baby into a family can have an impact on both parents.

“The father may also feel additional pressure to support the mother and if a mother is suffering with perinatal depression, the father can also feel the impact of this.

“The financial pressures of Covid and socially isolating time with home schooling must have been additionally difficult in recent times.

“It is very important that men suffering with perinatal depression talk about it. It is important to raise awareness.

“GPs and health visitors need to be able to identify and support new fathers as well as mothers.”

OPINION: The mental health of new fathers must not be overlooked

Michael has launched a consultancy called LETs (Lived Experience Trauma Support) offering corporations advice on how to support people with mental health problems in the workplace.

He said: “In Scotland, we still believe in the stereotypes about men and we don’t talk about things and it becomes part of the narrative of our life.

“We need to get over that.”

Minister for Mental Wellbeing and Social Care Kevin Stewart said: “Looking after the health and wellbeing of new parents is vital, both for them and their children.

“That’s why we provided £50 million funding to improve mental health provision for families throughout pregnancy and during the postnatal period.

“We are working with health boards across Scotland to develop and expand specialist Community Perinatal Mental Health services in every area as a priority.

“It is crucial that perinatal and infant mental health services are led by the needs of women, young children and families, so we will continue to build on good practice and learn from experiences of current services.

“We are also working to enhance staffing in Mother and Baby Units, and to support services provided by the Third Sector, such as counselling and befriending. Women can be admitted to a Mother and Baby Unit no matter where they live in Scotland, if they are in need of this specialist service.

“We have introduced the Mother and Baby Unit Family Fund to provide support with travel costs and other expenses to ensure that women in mother and baby units can benefit from visits and support from their families.

“Our Perinatal and Infant Mental Health Fund provides annual funding of up to £1 million to help Third Sector organisations deliver vital services.”

What is perinatal depression?

Perinatal depression is wide term for a mood disorder that can occur during and after pregnancy.

Antenatal depression occurs while you are pregnant, postnatal depression occurs during roughly the first year after giving birth and perinatal depression can happen at any time from becoming pregnant to around one year after giving birth.

There is a difference between the “baby blues” and perinatal and postnatal depression.

The “baby blues” is a colloquial term for brief period of low mood, feeling emotional and tearful around three to 10 days after you give birth. You are likely to be coping with lots of new demands and getting little sleep, so it is natural to feel emotional and overwhelmed. This feeling usually only lasts for a few days.

Perinatal depression is more serious and longer term. It can be gradual or sudden and can range from being mild to very severe.

Common signs and symptoms include:

- Feeling down, upset or tearful.

- Being restless, agitated or irritable.

- Feeling empty and numb.

- Being isolated and unable to relate to other people.

- Finding no pleasure in life or things you usually enjoy.

- Feeling hostile or indifferent to your partner or baby.

- Suicidal feelings.

There are various treatments for perinatal depression. These include: talking therapies such as cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) or interpersonal therapy (IPT), medication such as antidepressants.

The mental charity Mind also recommends self-care for perinatal depression.

If you have been affected by issues discussed in this investigation or are in need of support, contact Mind’s Infoline on 0300 3231545 or visit the website to find out about support in your area.

PANDAS offers information and support for people experiencing antenatal and postnatal depression.

Maternal Mental Health Scotland is also a valuable resource.

Where possible, ask for help from those around you. Practical and emotional support from family, friends and community can be vital in helping people to cope.

If you would like to speak to our Impact investigations reporter Stephen Stewart please email stephen.stewart@dctmedia.co.uk

More from our Impact team

The Hidden Hurt

Three women… One stabbed to death. One raped. One took her own life. A special investigation into domestic abuse being suffered by young women in Scotland.

Full series

MLM: A financial saviour or an easy way to lose money?

For this investigation, we spoke to women from our area about their experiences of multi-level marketing. Many told us stories about how they lost hundreds of pounds after signing up but others say they did find success, particularly during the pandemic.

Conversation