Firefighters reveal, for the first time, the tactics they used to battle the ferocious Morgan Academy fire, to mark its 20th anniversary.

Unheard testimonies from key firefighters, senior fire offices and control room staff disclose an insider’s view of an impossible fight, fraught with challenges.

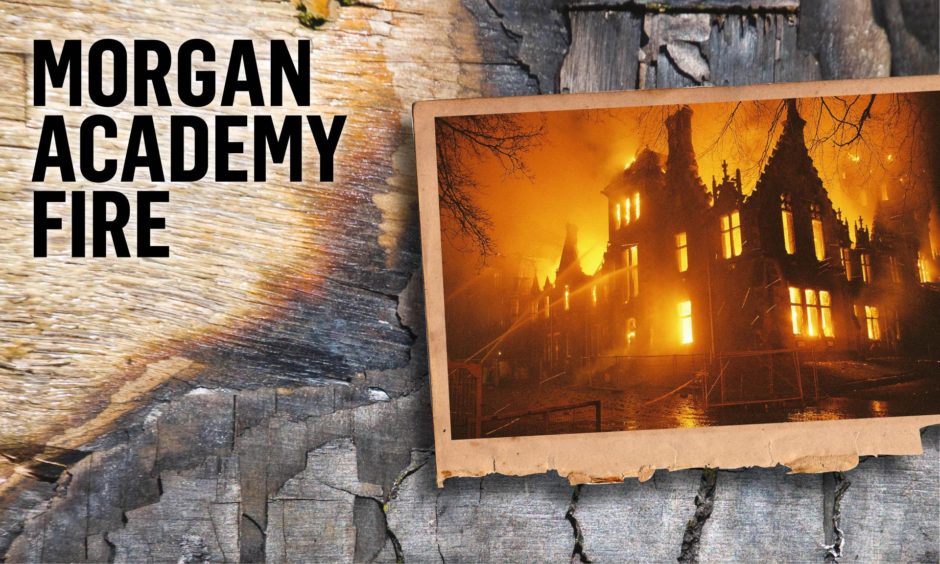

Unseen pictures taken by off-duty firefighter Ed Thomson depict a closer view of the inferno than ever before – scenes which shocked even the most experienced in the fire service.

Hear from the firefighters who went into the building and encountered a wall of flames, and from the aerial platform operators who had a unique viewpoint on one of Dundee’s most unforgettable nights.

In their own words, we bring you the story as you’ve never heard it before…

5.17pm on March 21, 2001

It was rush hour on a blustery evening when the first signs of what would become one of Dundee’s biggest fires were spotted.

Plumes of smoke billowing from the top of the science building at Morgan Academy pierced the sky – moments later it was filled with an orange glow, seen as far as Fife.

Unaware of the rapidly developing fire in the roof space above them, teachers prepped for that evening’s parents’ night, while cleaners worked busily.

Many of the pupils and staff, including then rector Alan Constable, were at DISC (Dundee International Sports Complex) watching Morgan’s hockey team take on Strathallan in the boys’ under-18s Scottish Cup.

A concerned member of the public made the first call to the former Tayside Fire and Rescue Service reporting smoke coming from the school, at 5.17pm on March 21, 2001.

Stella Rae, watch commander at the service’s command and control centre, took that first call.

She said: “I wasn’t initially expecting it to be the scale that it was, but we had nine or 10 calls in the first five minutes and that suggested it was a genuine fire.”

At 5.19pm control dispatched five appliances – three pumps (standard fire engines), an aerial ladder platform (ALP) and an emergency tender.

35 calls in 30 minutes

A further 35 calls to emergency services reporting the same incident were received by control over the next half hour, some from Newport and Tayport, in Fife.

On the ground, firefighters reached the scene at 5.23pm. On arrival they requested a further two pumps and a second ALP from control, in what is known as a make-up call.

Stella said she could hear adrenaline in firefighters’ voices, suggesting the scale of the incident.

Retired firefighter Eddie Bree, then station officer at Kingsway fire station, was one of the first to attend the scene with his blue watch crews.

Eddie, a firefighter for 30 years, said: “At the top of Kingsway, at the circle, we could see a plume of smoke and as we got further down we realised it was Morgan.

“We went down Pitkerro Road and saw a raging fire in the roof, towards Forfar Road. It was going well already.

“I thought ‘No way I’m home before midnight’ – the amount of smoke that was halfway down Pitkerro Road, it was quite a spectacular sight.”

Operation evacuation

The school’s smoke alarm was going off when Eddie’s crews arrived and there were teachers and staff inside the building.

He said: “I looked in the main door and there were still cleaners cleaning floors – while the smoke alarm was going off.

“There was no smoke in the building so they might not have been aware there was an actual fire but we had to get them out.”

While evacuating the school, firefighters managed to contact one of the janitors, Robert Coates, who came rushing from the hockey match to assist with a roll check.

His swift reaction raised a red flag for former head Alan Constable, who was rector at Morgan Academy for 18 years.

Alan said: “Someone in the crowd noticed smoke at Baxter Park area and someone else said they must be burning rubbish there.

“Then I saw the school’s janitor, whose son was playing hockey, on the phone and he flew off without saying a word and I realised it must have been a fire.”

Another janitor, George Anderson, who still has the role of facilities coordinator at Morgan and other schools in Dundee, was also notified.

George was on duty at Clepington School at the time and ran over to Morgan to help evacuate staff.

He said: “I went up the stairs and saw smoke coming from the turret then ran down to the bottom and looked up again and there were flames coming out of it.”

VIDEO: Watch our special documentary on the Morgan Academy fire

Race against time

Flames rapidly engulfed the school’s roof space and at 5.31pm – eight minutes after arriving at the incident – crews sent their first message to control confirming fire in the roof.

Craig Millar, a firefighter for two years at the time, arrived with Macalpine station’s blue watch in response to the first make-up call.

He was one of only four firefighters to enter the school wearing breathing apparatus and tackle the blaze from inside.

Craig, now crew commander of amber watch at Blackness fire station, said: “It was kinda strange because we went up the stairs and they were completely clear of smoke all the way.

“When we got to the top of the stairs there were two sets of doors with glass partitions and we could see an orange glow on the other side.

“When we went through the doors everything you could see was on fire.

“We went up with a hose and we were putting water out this small hose when as far as we could see was flames – we knew it was doing nothing.”

Craig says it was the biggest fire he had seen at that point and he was thinking there was “no way” firefighters could stop it spreading.

Craig says it was the biggest fire he had seen at that point and he was thinking there was “no way” firefighters could stop it spreading.

After five to 10 short minutes Craig and the other firefighters inside the building were evacuated with the emergency whistle signal.

He said: “We weren’t going any further in because there was no point but I did worry when I heard the whistle because that doesn’t happen often.

“What I could see was bad but I started to think it might be worse than what I could see. Bits of the building might have started to fall down.”

Officer Eddie decided it was not worth the risk of putting firefighters inside as the chances of the roof collapsing were “substantial”.

Firefighters evacuated

Eddie had arranged vehicles in strategic places, an ALP at either side of the building and tried to get to the fire from the top but says the slated roof presented problems.

He said: “We got up on a platform and tried to open the roof a distance away from where the fire was to tackle it from there but there was so much smoke that we couldn’t judge where access to the roof was.”

Describing the search for an alternative, Eddie said: “I went upstairs and could hear the fire roaring away, it was so loud.

“It sounded like wind rushing through a tunnel. By the time I came down the stairs the senior officer came on and took overall charge.”

That senior officer was Ali Hay – then divisional officer for Dundee, who later became the first chief fire officer for Scotland when the Scottish Fire and Rescue Service was formed.

Senior officers arrive

Ali had been driving home when he heard Eddie’s make-up message over the fire radio, asking for a total of five pumps and two ALPs.

He alerted control that he would attend, as he was required to do once fires reached that level, and was there within a minute.

Ali said: “When I turned up I could see already this was a significant fire.

“I had an understanding of Victorian buildings and knew there was a huge roof void with little to stop the spread of the fire.

“It had been there 100-plus years so the timbers were very dry and combustible and the fire was spreading rapidly. It was a very difficult fire and we were always going to have difficulty containing it in any shape or form.

“I remember going round the building to look at all angles and perspectives to assess the fire.

“I was only away from the front for about five minutes and by the time I was back there were hundreds of people there.”

Evacuated staff were stood outside and a crowd had started to gather – current and former pupils and members of the community, beginning to realise the gravity of the incident.

The fire ravished the building at speed, aided by strong winds on the cold March evening, just weeks before exam season.

Pupils could do nothing but watch in heartache as flames devoured their work.

Schoolwork and valuables destroyed

Headteacher Alan tried to no avail to save 133-year-old school logbooks and a valuable original painting by James McIntosh Patrick, both of which were in his office at the front of the building.

Firefighters told him the building was unsafe for them to enter and he broke down in tears at the reality of the situation.

He said: “I was in shock and then I began to realise this wasn’t a small local fire.

“At first I thought we might lose a few classrooms, then the science block, then the fire started to spread on to the roof and work its way through the whole school.

“I was devastated. All I could do was stand and watch as the school burned down with all the valuables inside.”

Firefighters quickly picked up on the sensitivity of the incident they were dealing with, witnessing the raw emotion from onlookers.

They could hear comments regarding lost schoolwork and concerns for the history and heritage of such a significant building in the city, which so many people felt connected to.

Divisional officer Ali said: “The sheer emotion from everyone there – staff, pupils, people who came to look, former pupils – we could hear their comments and were very conscious of what this building meant to people. It was an extremely significant fire.”

The fact the blaze was in the roof – designed to keep water out – meant crews had to wait for the fire to break through to gain access to the fire.

Grave concerns for the integrity of the building, backed by the views of the city engineer who was on the scene, left firefighting tactics restricted.

Ali said: “While the fire was inside it was burning quickly and our only way of getting to it would have been to put firefighters in, but that’s a massive decision because if the roof collapses on top of them, that’s the most common reason firefighters die.

“We were very conscious of that and decided we couldn’t get firefighters into the building when the fire was developing like that and with the old construct of the building.

“The real desire was to save as much of the building as we could for pupils but this was a huge fire above the heads of the firefighters and their safety is paramount, which is why we made the decision not to send them in.”

Police put cordons in place to close streets and keep the perimeter safe.

As the blaze continued to escalate at rapid pace, yet more senior officers were called, with then deputy firemaster Jack Hutcheon arriving on scene around 10 minutes after Ali.

Jack was second in command and took overall charge until the arrival of then firemaster Stephen Hunter.

Jack said: “I could see an orange glow in the sky from quite a distance away and when I got there, there were flames coming from the roof and all the top-floor windows.

“My first priority was to ensure there was no one inside the building and once that was confirmed then we were able to concentrate on the firefighting.”

The scale of the fire at Morgan meant the firefighting needed to be divided up into sectors and lower level officers took control of battling the blaze in their section.

Divisional officer Ali then took on the role of communication between these section officers and deputy firemaster Jack.

Water everywhere but not a drop with pressure

Jack’s immediate concern was sourcing enough water to give crews any chance of gaining control of the flames.

He said: “I’d done a quick recce of the site and knew by the number of jets we had there at the time that we needed considerably more water than we had.

“The water mains around the school were sufficient for the properties there but we were overdrawing it so we needed a larger supply.”

The possibility of emptying Swanny Ponds, on Clepington Road, using a relay of hoses to direct the water on to the fire was considered.

That idea was quickly ruled out as crews calculated it would only provide around 20 minutes of water.

Jack sought help from the water authority to increase pressure in the area at 5.44pm.

But a stronger source was still required to feed the platforms, which distribute around 2,000 gallons of water per minute.

Firefighters were tasked with finding stronger hydrants and Jack made a second make-up call to control requesting three more pumps at 5.50pm.

Eight pumps and two aerial platforms on scene

The timing at this point was significant, as 6pm was shift changeover for fire crews and control staff.

There were around 70 firefighters on the scene tackling the ferocious fire – all of whom were due to finish their 12-hour shift.

Night shift crews were arriving at stations and being shuttled to the scene in minibuses.

Deputy firemaster Jack said: “We had to manage numbers and crews and allocate them (night shift crews) to relieve the day shift crews while continuing to fight the fire.

“We had about 70 firefighters there, then another 70 came to take over, so at one point we have around 140 firefighters there and had to organise changeover systematically.”

A large part of the logistics of changeover was organised by control, who allocate resources to the fire and keep track of timings that crews have been on the scene.

The task involves the control team – just three people that night – communicating with officers, crews and stations, mobilising appliances between stations to ensure all areas are covered at all times, and contacting retained firefighters, who were also called to Morgan.

Shift changeover was going on in the background until 7.30pm while the scale of the blaze continued to grow.

The twin relay

Night shift crews were briefed on arrival and many, including former firefighter Jim Malone, were tasked with locating hydrants with a strong pressure.

Jim, who was an ALP operator and driver, went out in a Land Rover with Jack, and the pair located suitable mains at Baxter Park gates on Arbroath Road and a second hydrant on Eden Street.

Jim said: “We couldn’t get pressure at the hydrants around Morgan so we went looking for a stronger supply.

“It went on for a good while before the water board came and advised us there was better pressure at Arbroath Road.”

Jim was then required to help set up a twin line – two runs of hoses side by side – all the way up Baxter Park Terrace, along with a number of other firefighters including Graeme Curr.

Graeme said: “We had to pump from hydrant to pump, to fire engine next pump and so on, to make it more efficient to pump up the hills.

“It’s the only time I’ve ever seen the workshop staff out in trucks full of hose, throwing them off for the firies to roll them out and put them pump to pump.”

Damage control

Jack called for more resources at 6.14pm, requesting a third ALP which came from Fife.

His next concern was stopping the spread of the fire and limiting damage to the school and surrounding property.

Jack, who retired with 34 years’ service, said: “We knew the layout of the building and that there were limited constraints to prevent it spreading so the fire progressed dramatically and rapidly because the timbers were dry and there was no separation across the roof space.

“The bulk of the fire was at the rear end of the building but it spread towards the front – it became engulfed very quickly.”

Many involved in fighting the fire say constraints, or fire walls, within the roof space would have contained the fire to one small section of the building.

However, the age of the building meant these were not part of the original design and 20 years ago there were no legal requirements to add them, even in public buildings.

Onlookers watched in horror as the building started to collapse inwards.

Burning timbers from the ceiling collapsed into the floor below and caused the floor to ignite.

Firefighter Jim said: “Everything fell into the centre of school. The damage was visible. The inside was wrecked.

“The roof started to come in and the main issue was to keep the integrity of the building. You don’t want to see it fall in.

“A good bit was saved around the facade but the inside was devastated.

“Fallen roof timbers, brickwork falling through ceilings and walls, it all became a big, seething, bubble of fire. We were doing what we could to reduce heat and prevent further damage.”

Ten fire engines and three aerial platforms

At 7.32pm a further make-up call was made for two more pumps, bringing the total to 10 pumps and three ALPs.

Flames reaching as high as 10 metres were consuming the building.

The school’s iconic clock tower became engorged and at 7.45pm it collapsed, leaving a large hole behind.

Retired firefighter Ed Thomson, who was off duty that night but a keen photographer, arrived moments before the tower’s collapse.

He managed to photograph the tower in its last minutes of standing and then took the stunning pictures of the fire which we are sharing here with the public for the first time.

Ed, a firefighter for 32 years, said: “It was a ferocious fire – it was monumental.

“When I drove up and got out of my car and saw the tower, the pinnacle of the building, I could see it was going to go.

“I took a few pictures then seconds later it was down. Everything started to collapse.”

Devastation as tower collapsed

The demise of the tower sparked a change in the atmosphere among the hundreds looking on as they realised the school’s very existence was now under severe threat.

In the crowd, Diane Salisbury, the school’s principal teacher of guidance, says initial excitement was replaced with a sombre atmosphere and people started crying.

Diane said: “When the tower collapsed that was kind of like, that’s it. We’re not going back there.”

English teacher Lisa Devlin, who also witnessed the fire, says she felt “completely gutted” on a professional and personal level.

She said: “The gasp that went round the crowd – you could have heard it from halfway down Albert Street.

“It was really emotional and quite a sight to see it crumble. I’d grown up in the area and it was such a beautiful addition to Stobswell.

“There was a fear that it wouldn’t be rebuilt and that was very real.

“As we stood watching we couldn’t imagine that they would ever be able to recover anything from it because it was just so consumed.”

Nowhere was the damage more evident than from the top of the ALP, which reaches up to 30 meters above ground, as high as the ninth or tenth floor of a multi-storey.

ALP operator Graeme said: “I couldn’t get too close. If you tried to fight the fire over the top of it you would have got roasted. There was an intense heat coming off it, so I went higher than it but further back.”

Once the roof collapsed, Graeme was able to get closer as the flames were lower down, taking care to position himself away from the smoke.

His vehicle was on the Forfar Road side of the building, with the other two ALPs on the front and Pitkerro Road sides.

At one point he took a senior officer up on the platform to assess the fire.

He said: “We were high above the school. I looked down and I could see into all the classrooms and they were all on fire.

“It was quite a sight to see, I’ll never forget it.

“The roof had caved in and all three floors had fallen in. Everything was burning – the classrooms I could see were on the ground floor.”

Night-long inferno

The incident was so intense that firefighters’ roles were rotated often to allow for rest and recuperation, and most crews were relieved after they had spent around four hours at the fire.

From 8pm specialist units were sent to the scene, including catering facilities and welfare units, organised by control.

Control operators were also frantically logging everything that was going on at the scene, including how the fire was developing, requests for resources and communication with senior officers.

Jackie Cargill, who has worked in control room for 42 years, was one of the three operators on duty that night.

She said: “It was very challenging. The whole time we were getting radio messages updating us what was happening at the incident – the radio was very busy.

“We (control) work a 14-hour night shift to 8am and everything continued the whole night.

“It was one of these instances where there was constantly something to be done, the phone was ringing or there was a message on the radio coming in.”

Jackie says the team were “fortunate” that no other incidents broke out that night, but it was a mentally draining shift for her and her two colleagues.

Stop message received after five and a half hours

Around 9pm the fire passed its peak and, as it started to die down and firefighters gained more control of the blaze, crews began to retreat.

At 11pm the stop message was received, meaning that no more appliances were required and the fire was under control.

But firefighting continued into the night and the incident was not closed until the last engine left at 11.30am the next day.

As they left, only the three outer walls at the front and cast iron supports were left standing – an empty shell of a building, Morgan Academy was 80% destroyed.

Jim said: “I used to drive past it a lot and was sad when I looked at it.

“I heard comments about how the firefighters didn’t do their jobs properly but then you would explain to them and they understood.

“You always learn at a job and come away wondering if you could have done anything different – but not really.

“We did everything we could, got water where we could and there was no loss of life, so in that sense it was a success.”

Finding the cause

Fire investigators attended the following morning to assess the damage and search for the fire’s starting point.

Steve Mellon, former fire safety officer for 12 years, carried out the investigation and produced the fire report.

Steve, who retired with 30 years’ service, said: “The building had almost been burned to the ground so the difficulty for us was getting in.

“Some of it was still on fire. There were bits burning away and smouldering.

“It was too unsafe to go in so we walked around it and looked from all angles.

“The roof was completely gone – that was where it started – so we did a lot from the outside.”

Fire safety officers spoke to staff at the school and police also conducted interviews.

Police shared CCTV footage with the fire service, proving that no youths were involved, as had been rumoured, and clearly showing the exact location of where the fire started.

Dundee City Council also shared pictures of roof repairs being carried out to the school that evening and the location of where the work was taking place.

Steve said: “They were very good photos. When we saw where the work was, combined with the CCTV, we were able to pinpoint exactly where the fire started.

“That meant we were able to rule out the possibility of kids being involved because there were no kids on the CCTV.

“All the evidence matched the work to the roof being the cause.”

Tradesmen had been using blowtorches to apply felting to the roof. They were said to be unhappy with the method and fire extinguishers had needed to be used twice during the day of the fire.

Two other possible causes, electrical fault and a defective heater, were quickly ruled out due to the scale of the damage.

A headteacher’s nightmare

It had quickly become clear that youngsters would not be able to return to school for the foreseeable future and rector Alan Constable began to make arrangements for his 1,000 pupils.

Even as flames soared from the 133-year-old building, Alan worked quickly to communicate with Dundee City Council’s then chief of education, who was also at the scene.

Alan was aware the former Rockwell High School building, on Lawton Road, was previously used by St John’s High School on a temporary basis and thought this the best option.

Other solutions such as splitting the school into year groups and sending them to various other schools across the city were discussed and ruled out in favour of keeping pupils together.

A meeting with the council’s chief executive of education first thing the next morning confirmed the move to the old Rockwell building and an announcement was sent over the radio to notify staff and pupils.

Alan said: “I didn’t get much sleep that night. When I woke up I wondered if I had been dreaming.

“I went straight to a meeting at Tayside House, then on to Rockwell to meet staff.

“As I briefed them, there were joiners taking boards off the windows – the building was completely empty – and that sort of thing continued for some time.

“All we were provided with was 100 chairs and toilet paper. We had to contact other schools to borrow desks and materials. It was a pencil and paper education to start with.”

Despite the difficulties, and to the credit of everyone involved, pupils returned to school within two to three weeks, with year groups brought back in a phased return.

Former departments at the Rockwell building were gradually reinstated including science labs and home economics rooms, and temporary huts were built to accommodate the large number of pupils.

Alan said: “It was pretty traumatic at the time but, like every bad situation, it brought us closer – the staff and the pupils. It was an odd positive spirit.”

Negotiations with the exam board over lost work were successful and most youngsters received their expected grades, with the help of teachers’ assessments and any pieces of work teachers might have had at their homes.

Alan said: “We did think there might be some work in lockers but nearly all of the lockers were burned inside.

“We managed to open some of them. Bottles of hairspray had exploded inside them and there was very little which could be salvaged.”

The damage to Morgan Academy was almost overwhelming. All but three outer walls and their cast iron pillars had been destroyed, and so followed a £20 million restoration project.

Phoenix from the ashes

Alan became heavily involved in the rebuild, so much so that when he retired from his rector’s post, he was head-hunted by the construction firm, Balfour Beatty (formally Mansell), as an education specialist.

Being a Grade A listed building, collaboration with Historic Scotland was required and much of the new school was rebuilt in imitation of the original.

Hundreds of stones were hand carved on site by stone masons to recreate the beauty of the old Victorian building, while incorporating modernisation of class sizes, corridors and other facilities.

Alan said: “We didn’t just want to rebuild it – we wanted to make it better than it was before because it was in desperate need of refurbishment.

“The classrooms were very small. In some ways it was a blessing in disguise being able to modernise the whole school and we got to keep lots of the original features as well.”

In 2005 the project was completed and staff and pupils were able to move back into the Morgan, having spent more than three years at the former Rockwell High building.

Morgan Memories: Did you witness the fire, or have a story or photos to share? Get in touch by emailing cpeebles@dctmedia.co.uk