If you’re celebrating St Andrew’s Day today in a blur of ceilidhs and tartan, stop for a moment to think about Andrew, the humble fisherman who became a saint.

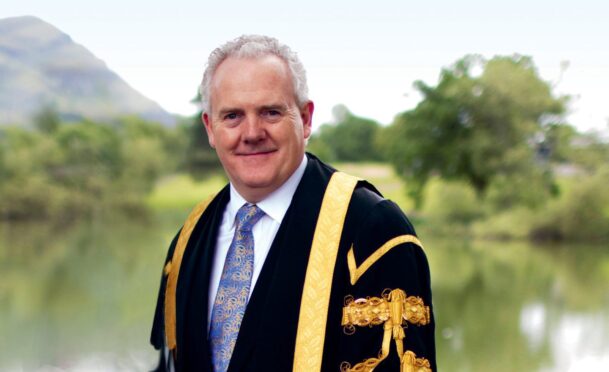

Dr William Hyland, a lecturer in church history in the School of Divinity at the University of St Andrews, explains: “Andrew was a fisherman in 1st Century Galilee.

“According to the Gospels of Matthew and Mark in the New Testament, Andrew was a fisherman who was called by Jesus to be an apostle and disciple.

“Andrew was the brother of Simon Peter, the future St Peter. According to John’s gospel, Andrew was at first a disciple of John the Baptist, and then was the first called by Jesus to be his own disciple.

“It was Andrew who then introduced his brother Simon Peter to Jesus. According to later tradition and legend, after the death, resurrection and ascension of Jesus, Andrew travelled as an evangelist throughout northern Greece, modern Turkey, and even parts of Ukraine, Romania and Russia.

“According to tradition he was crucified by the Romans on November 30 in the year 60AD in Patras in Greece, bound to an X-shaped cross known as a saltire.”

Although no portraits of Andrew exist from this time, he is usually portrayed in art as an older man with long white hair and a beard.

“He is sometimes shown holding a gospel book or fishing net, sometimes preaching, sometimes leaning on a saltire, or actually being crucified on the saltire,” adds Dr Hyland.

Author and journalist Norman Watson, who writes The Courier Weekend’s weekly antiques column, recalls being inspired by a painting of St Andrew.

“As a boy – probably no more than aged 10 or so – my Sunday afternoon walk often took me to Perth Museum & Art Gallery. Back then, all three floors were used, with the mummies and shrunken heads in the basement probably the biggest attraction for a nipper. But it was the sensational painting of St Andrew by Josef Ribera which helped nurture a love of art.

“Ribera, a leading painter of the post-medieval Spanish school, shows the highly naturalistic St Andrew, bearded, skeletal, semi-naked and gazing heavenwards in pain and suffering. Much in the style of Caravaggio – dark, shadowy and gloomy – it probably scared me a bit!

“It is a wonderfully-dramatic and very precious Old Master and, with all the comings and goings, it has never left the wall where I first saw it half a century ago.”

While numerous churches and schools are named after St Andrews, how did the little Fife town of Kilrymont on the east coast of Scotland take on his name?

“In the medieval period, it was believed that relics, or certain bones of St Andrew, were present in this town which at first was known as Kilrymont, and then took its name from the relics of the saint which were venerated there and became a source of pilgrimage,” explains Dr Hyland, who specialises in Medieval church history and theology, with a particular focus on monasticism and spirituality, including teaching about pilgrimage in medieval St Andrews.

“According to a later legend, these relics of St Andrew were brought to Fife by St Regulus, who later became known by the shortened name St Rule.

“What more likely occurred is that relics of St Andrew were brought from Rome to England by Catholic missionaries in the 7th Century, and then from England some of them brought to Kilrymont by a certain Bishop Acca in the 8th Century.

“These relics helped make the town of St Andrews very important in the medieval Scottish church, and eventually the great cathedral and priory were built to serve as a shrine for these relics and a centre of pilgrimage from all over Scotland and far beyond. Out of this cathedral school grew the University of St Andrews.

“St Andrew seems to have been a very important saint in Fife and lowland Scotland in general in the early middle ages and this importance was strengthened by the presence of his relics in St Andrews,” says Dr Hyland.

“Later legends associated his patronage of the Scots with a vision that he appeared to a Pictish king the night before a battle, with a white X-shaped cross (the Saltire) seen against a blue sky.

“However, the celebration of Saint Andrew as a national festival is thought to originate from the reign of King Malcolm III (1034–1093), and was greatly encouraged by his wife and queen St Margaret of Scotland and their sons,” he continues.

“In the later middle ages, especially during the 14th Century Wars of Independence against the English, St Andrew became explicitly associated with Scottish aspirations for nationhood, with the Saltire as the symbol of his patronage.”

Besides being the patron saint of Scotland, Andrew is also the patron saint of many other countries, including Ukraine, Russia, Georgia, Greece, Cyprus, Romania and Barbados. There are also many towns, cites and churches who have them as their patron, including Constantinople (now known as Istanbul) and Patras in Greece. Additionally, he is considered to be the patron saint of fishermen, fishmongers, rope-makers, textile workers, singers, miners, butchers and farm workers.

“I think in our part of the world it is always important and meaningful to be reminded that the first disciples of Jesus were drawn from fisherfolk, who went on to display such courage and fortitude in spreading his teachings,” reflects Dr Hyland.

So where does St Andrew fit into 21st Century Scotland?

“As well as St Andrew’s Day being a bank holiday in Scotland, the Saltire, or Scottish flag, is of course very important, both here in Scotland and among many people of Scottish ancestry all over the world, where St Andrew’s Day is often seen as a time to celebrate Scottish heritage,” says Dr Hyland.

“Up until very recently the university held its first semester graduation on or near St Andrew’s Day. Students were also traditionally given the day off from classes, while many events, concerts and religious celebrations marking the beginning of the holiday season can also coincide with this celebration.

“At the time of the Reformation in Scotland, the saint’s shrine and relics in St Andrews Cathedral were dispersed. However, some of them have been returned over time to Scotland, and are presently located in a lovely shrine in St Mary’s Roman Catholic cathedral in Edinburgh.

“Also, the Fife Pilgrimage Way is once again very active, with many people participating, all in their own way, in this medieval pastime.”