On the 75th anniversary of VJ Day, Michael Alexander looks at how the end of the Second World War in the Far East was marked with celebrations – yet often “overshadowed” by the end of the war in Europe three months earlier.

It was the day that Japan surrendered to the Allies after almost six years of the Second World War.

Seventy-five years ago, scenes of joy and celebration broke out around the world as August 15, 1945, was declared Victory in Japan Day (VJ Day).

US President Harry S Truman broke the news at a White House press conference the day before.

He confirmed the Japanese Government had agreed to comply in full with the Potsdam declaration which demanded the unconditional surrender of Japan.

At midnight, the British Prime Minister Clement Atlee – who had defeated wartime Prime Minister Winston Churchill in the general election just weeks before – confirmed the news in a broadcast saying: “The last of our enemies is laid low.”

He expressed gratitude to Britain’s allies in Australia and New Zealand, India, Burma, all countries occupied by Japan and to the USSR.

But special thanks went to the USA “without whose prodigious efforts the war in the East would still have many years to run”.

Later that night, King George VI said in an address from Buckingham Palace: “Our hearts are full to overflowing, as are your own.

Yet there is not one of us who has experienced this terrible war who does not realise that we shall feel its inevitable consequences long after we have all forgotten our rejoicings today.”

While much of the attention was on London where historic buildings were floodlit, towns and cities across the country, including Tayside and Fife, held their own celebrations, as recorded in the pages of The Courier at the time.

On August 13, in anticipation of a formal VJ Day announcement and a two-day public holiday, it was reported that Arbroath magistrates had decided to illuminate public buildings, ring church bells and sound sirens.

Bonfires were to be lit at the High Common and at Springfield Park with open air dancing.

In Dundee, it was reported on August 14 that several public buildings were also to be floodlit – minus a bonfire.

A wreath was to be placed on the Dundee Law War Memorial, which was to be floodlit, and the beacon on the top lighted.

The city chambers and the city churches were also to be floodlit. During the afternoon and evenings, bands were to play in the City Square.

The acting Lord Provost invited citizens to decorate their houses.

Carnoustie Town Council also agreed that church bells would ring and all the churches would be opened for services at 7.30 pm.

On the first of the two days’ holiday there would be a “sand designs competition for children in the forenoon, depending on the tide”.

Then, in the evening the Burgh Band would play on the links from 7.30 to 9 pm, after which there would be community singing.

At about 10 pm, a bonfire would be lit near the Links car park, and ships rockets would be fired.

On August 16, The Courier reported how attendants on lonely Atlantic lighthouses were allowed to speak to their wives and relatives ashore by wireless telephony – a concession which was suspended throughout the war for security reasons.

For many families, however, the pain and uncertainty brought by war would continue. In a report of April 22 1947, Mr A. V. Alexander, Minister of Defence, confirmed that casualties in the Royal Navy between VJ Day and April 14, 1947, were 63 killed and 52 wounded, and in the army from August 1, 1945, to March 31, 1947, 15,272 killed and 1627 missing.

The army figures included deaths from wounds received before August 1, 1945, missing or Prisoners of War whose death was established or officially assumed after August 1, 1945, and some who died before that date, but whose death was not notified until later.

RAF casualties from VJ-Dav to April 14, 1947, were also considerable including 44 wounded, and 24 missing.

It was May 29, 1948 before The Courier reported the ‘Last Man Demobbed at Ferryden’ at an ex-service personnel event attended by about 120.

VJ Day, as with Victory in Europe Day held a few months before on May 8, was a chance to finally reflect on the cost of war and the opportunity to look ahead to what everyone hoped would be a brighter future.

But according to St Andrews University historian Dr Derek Patrick, VJ Day events were often “overshadowed” by the end of the war in Europe three months earlier.

In Auchterarder, for example, local people were critical that the local council hadn’t taken the lead arranging celebrations.

Celebrations tended to be “off the cuff” with a feeling the authorities had been taken by surprise, Dr Patrick said.

Meanwhile, in Arbroath the local newspaper referred to VJ Day as “Q Day” as local housewives queued at the shops to bring in supplies for a two day holiday.

“I was looking at St Andrews and Auchterarder and various other places, and VJ Day tends to get off to a slow start,” he said.

“I think it’s the morning of the Tuesday at 12 o’clock when Clement Atlee makes the announcement that the war in the Far East was over, that the Japanese had surrendered.

“It seems to be on the Monday night that people, despite there being no official confirmation of the surrender, were actually told on a special newsflash at 11pm to anticipate news coming through.

“It does seem to be that folk were anticipating it – the end of the war in the Far East.

“In Arbroath there were thousands of people in the street after midnight. People climbing out their bed and putting their clothes on – going out for a dance.

“In Auchterarder there were soldiers stationed just up the road – they went for a parade up and down the centre of the town. There’s bagpipes.

“In St Andrews, there was the Lammas Fair – there were a lot of people kicking about in the town. “But despite that, when news comes through most people have gone home for the evening.

“On the Tuesday through the day it tends to be a wee bit of a slow start, but it kicks off with a bonfire and open air dances and things – it’s quite a spectacle.”

A number of years ago, Derek interviewed the late Alistair Urquhart, of Broughty Ferry, who was a soldier in the Gordon Highlanders captured by the Japanese in Singapore.

He not only survived working on the notorious Bridge on the River Kwai, but he was subsequently taken on one of the Japanese ‘hellships’ which was torpedoed.

Alistair’s account summed up the brutal treatment many went through and for many the psychological scars would stay with them for the rest of their lives.

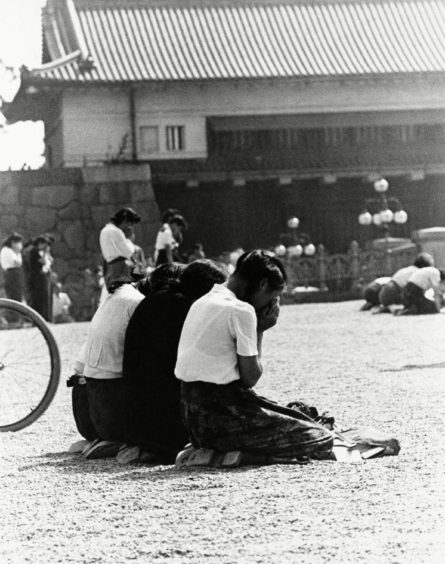

“With something like 90,000 casualties in the Far East including 30,000 deaths and around 13,000 prisoners of war, it takes a long time for many to get home and it’s a long process back to get these men back into society,” Dr Patrick said.

“For these men who were out there fighting in the Far East and the commitment they’d made, it must have been a huge relief for them and their families it was over.

“But trying to deal with the cost of that after the war and for these men to integrate back into society – it must have taken a long time. This was awful. These men would carry these scars for a long long time.”

Of course, the Japanese surrender had only come about because of the two atomic bombs dropped by the USA on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on August 6 and August 9 respectively.

It was a point made by Japan’s Emperor Hirohito who blamed the use of “a new and most cruel bomb” in his first ever radio broadcast.

It wasn’t fully appreciated at that time just how big an impact the nuclear arms race between East and West that followed would have on global geo-politics for the rest of the 20th century and beyond.

However, without the war ending when it did, who knows how much more bloodshed would have followed had it dragged on longer.