There’s been a murder.

Poor old Reeta Banerjee, a humanitarian lawyer of international renown, was found dead in her Dundee home shortly after her 85th birthday.

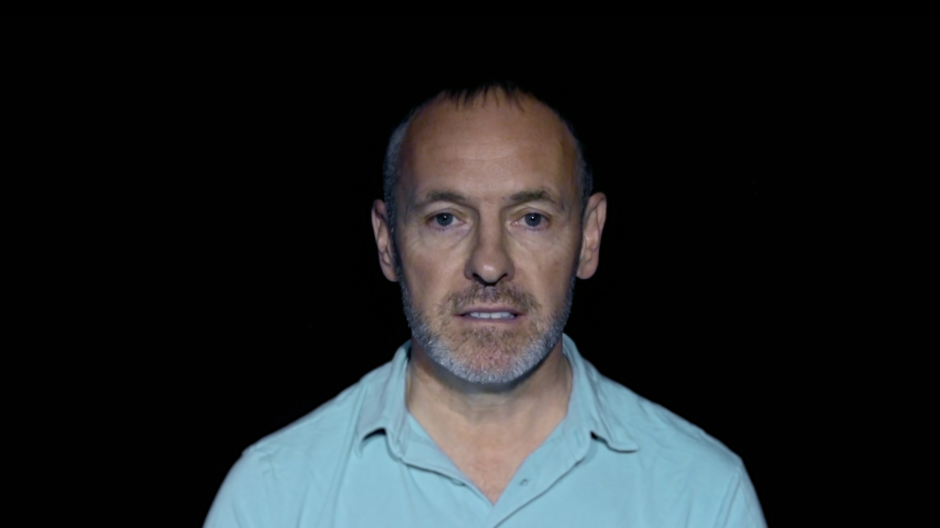

In the frame is Andrew Davidson, an out-of-work labourer with a violent past who claims to be a reformed character.

I’m one of the jury members who will weigh up the evidence and decide whether Mr Davison is guilty. It’s quite a responsibility. Get it wrong and an innocent man could go to prison for life, or the heartless killer of a defenceless old lady is free to walk the streets and strike again.

Thankfully it’s not such a disaster if we don’t get it right. Andrew Davidson is played by an actor and Reeta Banerjee is a figment of the imagination.

I’m taking part in the Evidence Chamber, which brings together a virtual jury and puts them through an experience similar to a real trial.

It’s a collaboration between the Leverhulme Research Centre for Forensic Science at Dundee University and theatre group Fast Familiar.

The production kicked off on July 24 and finishes its run tomorrow. Its premiere featured crime writers Val McDermid, Oyinkan Braithwaite and Craig Robertson on the jury.

William Shaw, Dervla McTiernan and Waterstones Children’s Book Prize winner Sharna Jackson are among other established crime and mystery novelists to have taken part.

The trial opens with a broadcast from “BNC 1 News” outside Dundee High Court (in reality Dundee Sheriff Court). It explains the trial of Andrew Davidson is about to begin. He’s accused of murdering Ms Banerjee in her home on Dundee’s Farington Street sometime on a Sunday night in January 2021.

The scene set, we hear witness statements from forensic experts, colleagues of the victim and friends of the accused. At various stages in the show we’re given a few minutes to deliberate. Before evidence resumes we’re asked to vote on whether we think the defendant is guilty or innocent, based on what we’ve heard so far.

“Obviously in a real trial you would hear all the evidence then go away and deliberate,” explains Fast Familiar playwright Rachel Briscoe. “But there’s a balance to be struck between accuracy and entertainment. We didn’t want our jury to have to sit through hours of video evidence before they could deliberate.”

There’s some intense debate among the jurors and, frustratingly, the evidence doesn’t always paint a very clear picture.

“When people see jury trials on television and in the movies everything is very neat and you always get a very complete narrative,” Rachel continues. “Real life isn’t like that. Trials are messy, bits of information you would expect aren’t there and you have to piece it together as best you can.”

In our case, a DNA expert confirms Davidson’s DNA was present in the house where the murder was carried out. There’s also CCTV footage of someone entering the building and a “forensic gait analyst” testifies that the man on the camera is very likely our suspect, based on the way he walks.

Set against that, Davidson has an alibi, having stayed at a friend’s house in Carnoustie, and his mobile phone’s location data confirms that his phone at least was in Carnoustie all night.

Colourful comics written for the production give us information on DNA and forensic gait analysis, to help us decide how much faith to put in the experts’ opinions.

In the end, after more deliberation, we agree there isn’t enough evidence to confirm beyond reasonable doubt that Davidson carried out the murder and we unanimously agree to acquit.

Rachel joins us in the virtual debrief afterwards and the question all of us want answered is: were we right? Was he innocent?

“You’re the jury and you found him not guilty so he is innocent,” she says. “In a real trial that’s how it works.”

It’s been tremendously entertaining as well as a fascinating insight into how trials work. There is another purpose to the Evidence Chamber, however, which could change the way trials are conducted.

Professor Niamh Nic Daeid is director for the Leverhulme Centre, which commissioned the piece. The forensic scientist has been an expert witness at numerous trials and gave testimony at the Grenfell enquiry.

She explains: “We wanted to look at how expert evidence is presented in trials and whether we can improve it.”

Whereas forensic DNA is well established and trusted, forensic gait analysis is a new field with little track record and no national database.

“We wanted to see how scientific evidence is perceived by jurors,” Professor Nic Daeid continues. “In particular whether more weight was given to the DNA evidence rather than the forensic gait analysis.

“DNA is very well established but gait analysis is in its infancy with little track record so we wanted to find out how jurors evaluated the evidence.”

Professor Nic Daeid hopes this research will feed in to how trials are conducted. “I don’t think remote trials will remain after covid but it may be that expert witnesses are pre-recorded so they can be more concise and easier for the lay person to understand.”

Sadly, however, it looks like the murder of poor old Reeta Banerjee will go into the cold case files and may never be solved.