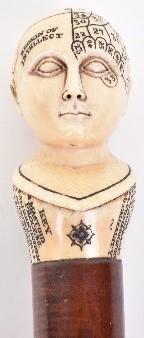

In 19th century Scotland, a Fife-based antiquarian was at the forefront of the controversial pseudo-science of phrenology. Michael Alexander finds out more this Halloween from Fife archaeologist Douglas Speirs.

He was the deeply religious damask designer based in Dunfermline whose designs were purchased by the Victoria and Albert museum in London after his death and whose children went on to become well-known artists themselves.

However, what’s less known about 19th century weaver and antiquarian Joseph Neil Paton is that he was a passionate collector of curiosities associated with witchcraft and played an active role in promoting the fledgling ‘science’ of phrenology – a misguided belief that you could infer much about an individual’s character and their traits from the study of their skull.

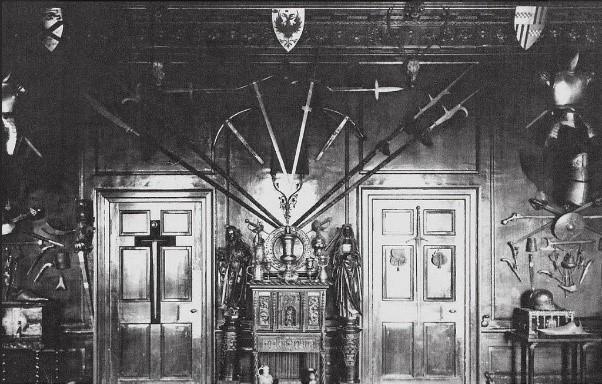

Paton amassed a nationally important private museum at his house in Dunfermline that was visited by the great and the good.

Among the exhibits were a table dated 1310 that had belonged to Robert the Bruce plus other furniture and memorabilia from royal households.

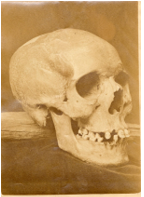

However, it was his active belief in phrenology that accounts for his drive to acquire historically significant skulls, such as those of ‘witches’ which he used not just as objects of fascination but also as subjects to practice and prove the ‘science’ of phrenology.

Paton paid for graves to be robbed all over Fife to serve his collecting interests.

One of the most notable skulls he acquired, however was that of unfortunate local woman Lilias Adie – the Torryburn ‘witch’ who died during interrogation in 1704 and who was buried on the foreshore at Torryburn in west Fife.

In 1852, he commissioned the opening of this – Scotland’s only known revenant grave – which, in line with the paranoid superstitions of the time, had been sealed with a half tonne slab placed over it designed to stop the dead returning from ‘beyond the grave’.

“The sad story of Lilias Adie, an accused witch from Torryburn, Fife, who died in 1704 of torture and was buried on the foreshore is well known, but what’s less well known is the story of her exhumation in 1852,” explains Fife Council archaeologist Douglas Speirs.

“The story was reported in newspapers across the country that ‘a party at Torryburn, stimulated by a desire of gratifying a celebrated local antiquarian, by presenting him with the cranium of a witch, dug up the remains of the famous ‘Lilly Eddie’.’

“The reporting of the story perfectly contrasts the difference of opinion over phrenology in mid-19th century Fife.

“Local antiquarian, Joseph Neil Paton of Dunfermline, an artist and a collector but no scholar, was a convert and devotee of phrenology.

“By obtaining the skull, he undoubtedly expected to see in it evidence of Lilias’ character as a witch.

“The editor of the newspaper, on the other hand, skilfully and subtly lampoons Paton using the language of phrenology in mockery by suggesting the whimsical idea that a witch’s skull should reveal evidence of an elongated crooked nose.”

Mr Speirs said Joseph Neil Paton’s obsession with phrenology reflected much of the eccentricity of his character.

An artist rather than an intellectual and a collector more than an antiquarian, he had an obsessive yet ill-defined spiritual belief verging on mysticism.

He dabbled with many religious beliefs. He was a Swedborgian – influenced by the writings of scientist and Swedish Lutheran theologian Emanuel Swedenborg – he was curious about the supernatural and the occult, and he even erected his own New Church chapel in his garden in which he preached.

Mr Speirs suggests, however, that if Paton’s belief in phrenology can be dismissed as a mix of “artistic gullibility and antiquarian curiosity”, it’s less easy to be so charitable to those who should have known better.

That’s because the science was firmly stacked against phrenology, and innumerable studies of the period confirmed this.

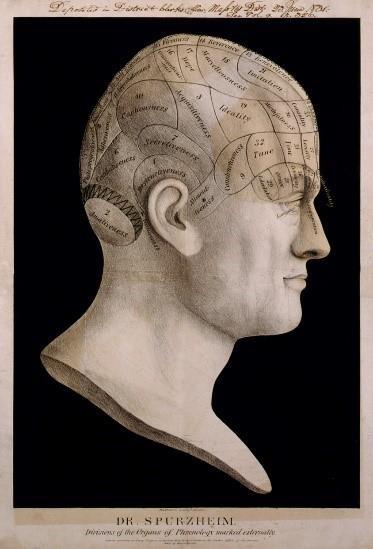

A detailed paper read before the Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh by its President, Thomas Stone, in 1829, presented the results of a thoroughly meticulous scientific examination of the skulls of Burke and Hare along with the details of the assessment of the skulls of a further 50 notorious contemporary murderers.

Stone contrasted the cranial observations of the deceased with the character traits claimed by the phrenologists, and utterly debunked the pseudoscience of phrenology as “utter quackery”, said Mr Speirs, finishing with a lengthy critique of the innumerable failings and the rank inconsistencies of the theory, noting that not one reputable man of science or medicine in Europe was a devotee.

Yet many 19th century men of medicine still believed steadfastly in the theory.

One of them was a doctor who in the 1820s recovered the skull of Bishop Kennedy of St Andrews from its 15th century tomb for phrenological study.

“The skull was ‘pronounced by connoisseurs to evince great firmness, conscientiousness, and veneration, but not that degree of intellectual capacity which might have been expected from the well-known ability of the illustrious prelate’,” recalls Mr Speirs.

“Similarly, it was a doctor who broke into the tomb of poet Robert Burns in 1834 to steal the skull of the national bard for phrenological study.

“And it was Doctor J Barnard Davies of St Andrews University who in analysing some 16 medieval skeletons found on the Kirkhill in St Andrews in 1860, discarded the skeletons in the belief that only the examination of the skulls had the potential to shed light on the deceased.”

In 1884, Dr William Barrie Dow of Dunfermline, first president of the newly founded Fifeshire Medical Association based at St Andrews University, acquired the skull of Lilias Adie from Paton’s son, Waller Hugh Paton.

His interest, like Joseph Neil Paton’s, was the scientific study of a witch’s skull. Phrenology had been utterly debunked as a pseudoscience by this date.

Yet the paper he read to the Fifeshire Medical Association at St Andrews on September 30, 1884, was well-received and in circulating the skull for examination at his talk, the anatomists of St Andrews University all agreed that the evidence of both her base character and her propensity towards witchcraft was readable in her head shape.

Mr Speirs said there’s no doubt Joseph Neil Paton’s obsession with phrenology had a deep influence on his antiquarian collecting and explains the presence of skulls in his collection.

However, Lillias Adie’s was not the only Fife skull in his collection.

He had at least two others including that of Jenny Nettles, the tragic Falkland beauty immortalised in song.

Paton believed the skull could reveal the cranial traits of someone given to suicide.

“The story goes that after the Battle of Sheriffmuir in 1715, the famous Rob Roy MacGregor was sent to take Falkland Palace for the Jacobites,” says Mr Speirs.

“It’s claimed that one of the Highlanders in Rob’s band of men met a local beauty called Jenny Nettles.

“The soldier seduced this impressionable young maiden, then when the Jacobites left, poor Jenny found herself abandoned and with child.

“Wracked by shame and ostracized by her local community, Jenny hanged herself on a tree in the wood of Falkland a little to the north of the village.

“Her body was taken and buried between the land of two lairds and the site marked by a cairn.

“In reality, it appears that the father of her baby was in fact a local chapman and that the exact date and circumstance of events is not entirely clear.

“But what is clear, is that the sad story was immortalised in song within 50 years of the tragic events and that as with so many popular Scottish folk songs, it was actually an old tune that was married up to new words.

“Interestingly, what seems to have made this all too common story stand out was actually the unusual events of Jenny’s discovery –recorded in 1838 by local folk memory.”

Mr Speirs said clearly, the scandal and difficulty of Jenny’s circumstances as an unmarried mother in early 18th century Scotland was too much to bear and sadly, like so many women in her condition at that time, she took her own life.

As a suicide, she was denied burial in the parish cemetery and instead, was buried under a cairn on Falkland Muir, at a lonely spot commonly reserved for the burial of suicides.

However, in about 1827, James Whyte of Corston Tower, Strathmiglo, had the site investigated and the skull of Jenny Nettles was retrieved and later sold to Joseph Neil Paton.

“Why did Paton so covet it?” asks Mr Speirs.

“Like the skull of Lilias Adie, it fulfilled his two all-consuming passions: the collection of antiquarian curios and phrenology.

“Just as the skull of Lilias Adie afforded the opportunity to use phrenology to reveal the cranial traits of a witch, so the skull of Jenny Nettles afforded the opportunity to use phrenology to reveal the cranial traits of a notable historical figure given to suicide.”

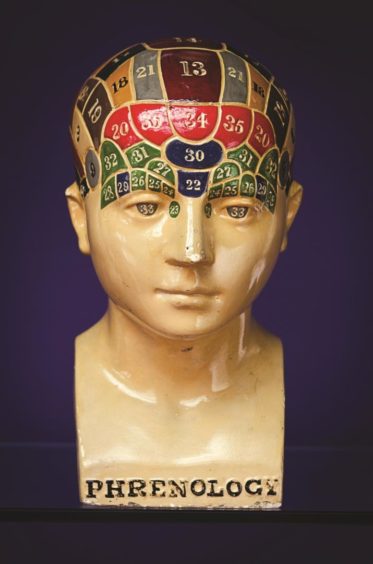

The phrenology debate split the scientific community of Scotland for much of the 19th century and it’s a subject that spilled over heavily into anthropology, archaeology and history, used to explain everything from intellect to witchcraft and to justify everything from racism to imperialism.

Many past societies had of course proposed links between an individual’s appearance and their inner character.

Ancient Greek poets such as Zopyrus touched on the subject. Greek philosophers such as Aristotle believed in it.

The Chinese believed strongly in the ‘science’ of face-reading (physiognomy) in the 11th century whilst John de Rhetan published a very obscure medical treatise in Venice in 1500 which can be shown to be the source of much of what was later to be passed off as the research of Franz Joseph Gall, the modern founder of phrenology.

When Gall’s lectures were banned by the Austrian government in 1802 as dangerous to religion, however, it was his devoted young student assistant, Johann Gaspar Spurzheim, who helped develop his theory of craniology further by promoting his theory across Europe.

From the first publication of the phrenological theories of Spurzheim in English in 1814, the idea was ridiculed and praised in almost equal measure, the informed doing the ridiculing and the gullible doing the praising.

But in all of Europe, it was in Edinburgh – now home to Edinburgh University’s impressive Anatomical Museum which consists of approximately 12,000 objects – that the subject was most hotly debated and it was across Scotland that the idea was most widely applied to the study of the past.

Last year, Rachel McGarvey, an MSc Forensic Art student at Dundee’s Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design, painstakingly recreated the visage of Archie Flockhart, a well-known character on the streets of 19th-century Dunfermline, whose skull is now part of the Edinburgh University collection.

Described in the book Reminiscences of Dunfermline as a ‘poor half-witted creature’ who sadly, was routinely mocked and even physically assaulted by members of the public, he eventually ended up in Dunfermline Poorhouse.

He was notable for a distinctive growth on the right side of his upper jaw, and when he died in 1877 aged 75, this is widely believed to be the reason that his skull was preserved for further phrenological research.

Mr Speirs adds: “Ironically, the energy and enthusiasm of the early 19th century Edinburgh scientific community’s rejection of phrenology in reality, actually served to shine a light on the subject.

“However, like astrology, horoscopes and fortune-telling, no amount of science could stamp it out and as its popularity waned in Britain in the 1840s, it re-surfaced in America where it enjoyed considerable popularity until the end of the 19th century.

“It even made a come-back in Britain in the second half of the 19th century and was paraded as science in order to justify British Imperialist expansion and racism.

“But ultimately, informed science abandoned it and moved instead towards anthropometry, criminology and psychiatry.”