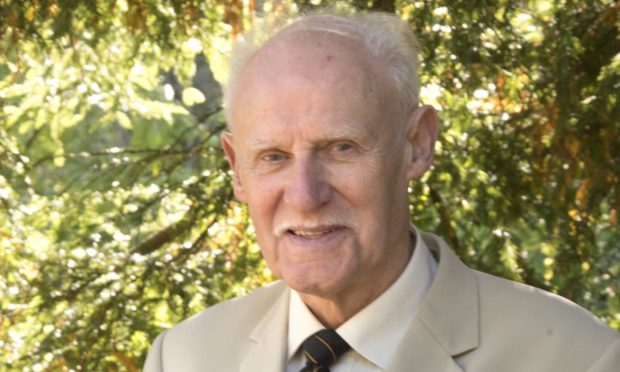

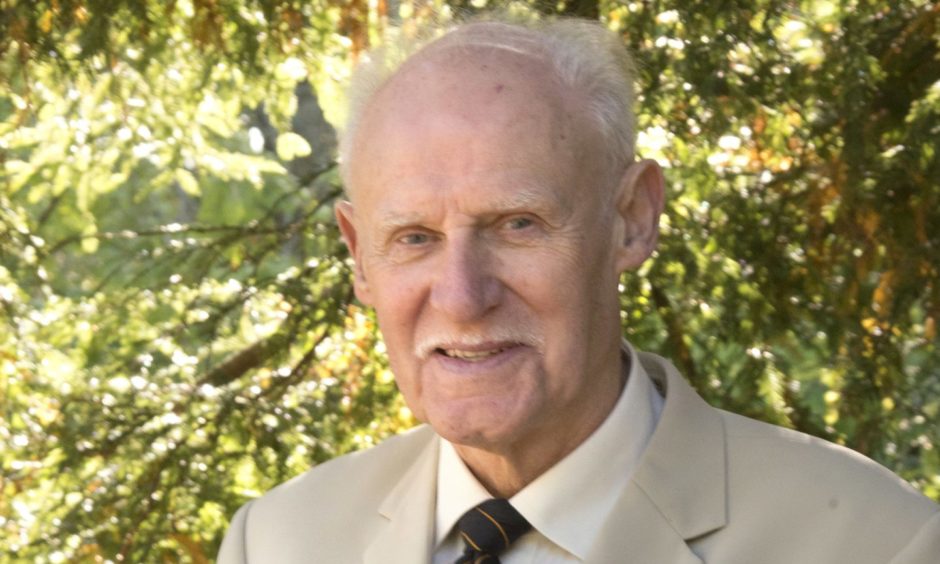

Michael Alexander hears why St Andrews-based author Lorn Macintyre yearns for the old days when Scottish Travellers were revered and trusted as an important and ancient part of Scottish rural life.

When St Andrews-based author Lorn Macintyre was growing up at Dunstaffnage House in Argyll and Bute, he vividly remembers a tinker called Willie who would arrive at the house every year “like a cuckoo”.

Lorn’s bank manager father Angus, who conversed with him in Gaelic, always welcomed the Traveller with whisky and the family would give him old clothes and food.

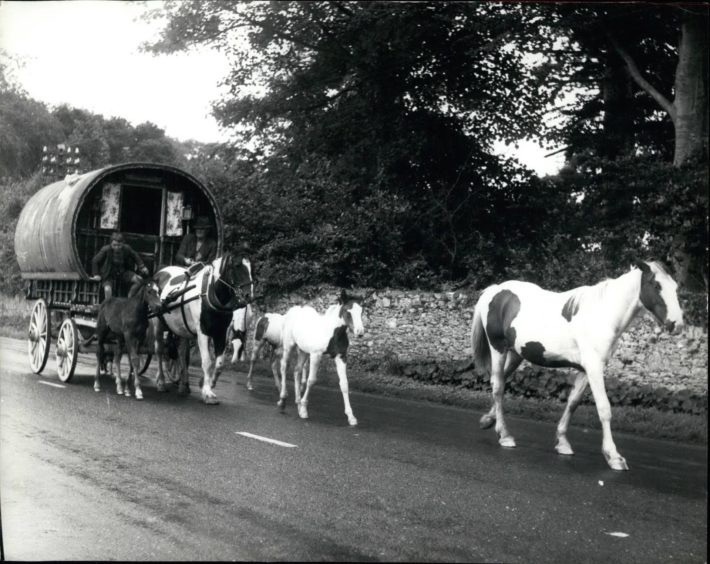

Regarded as an ancient and rich part of Highland culture, and with links to other Traveller communities across Europe, tinkers were, at the time “really revered in the countryside because they were personable people”.

Lorn says: “They were called tinkers because they were skilled in making things out of tin. They would go round doors in early summer fixing kettles and teapots, and repairing these items.

“They sold clothes pegs and wooden flowers which they had fashioned themselves, and they were a source of labour for farmers, helping to bring in the harvests of fruit and crops.”

In those bygone days before motorised traffic increased, Lorn recalls their carts pulled by horses at a leisurely pace towards traditional stances where they had pitched bow tents and lit campfires for generations.

But in the decades since, Lorn has been saddened by the way in which tinkers and Travellers have been discriminated against, abused and denigrated by society, almost to the point of cultural extinction.

He adds: “I think the way that some people have come to regard them is a form of racism – as if they are an inferior race when they are by no means an inferior race.

“I’m afraid they were a people who were despised in many quarters maybe because people were frightened of them – rooted in Scotland’s superstitions.

“They thought they had paranormal beliefs and could do things to us. That they could put a curse on you if you didn’t do what they wanted. They thought they were thieves when they were not. They only said that because they don’t understand them.”

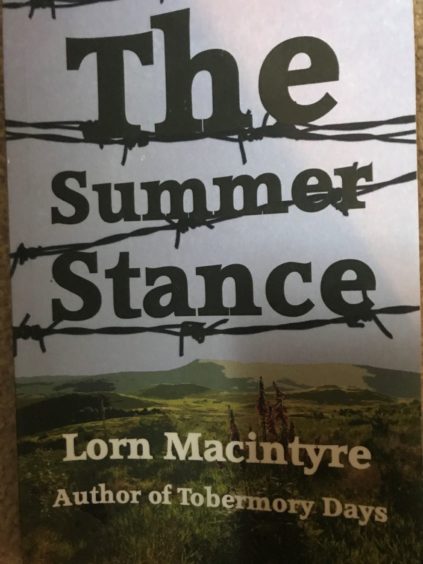

The Summer Stance

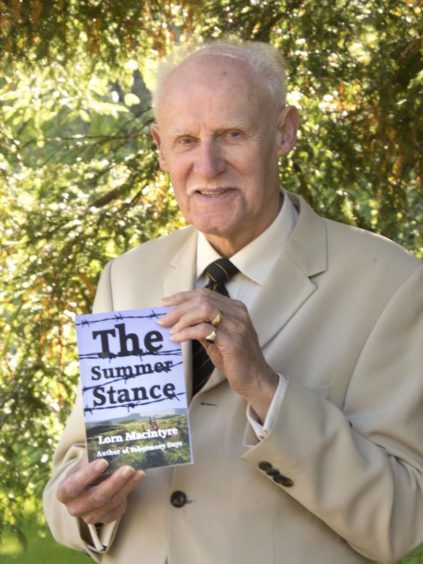

It’s into this world that Lorn, 78, steps in his recently published novel The Summer Stance, which celebrates the tinkers way of life.

Set in the 21st century, the main character is Dòmhnall Macdonald, a boy raised in a Glasgow tower block with his tinker family, who no longer move out into the countryside for the summer.

Dòmhnall spends a lot of time with his blind grandmother, his tutor in Gaelic.

He learns about their summer stance, Abhainn nan Croise, the River of the Cross, so named because a stone cross was found there by a holy man and paraded for veneration round Scotland.

The site becomes a place of enchantment to the boy as he learns about the horses that took the Macdonald family there and the Gaelic names for the otters, birds and plants that the old woman, the Cailleach, remembers.

When she is diagnosed with terminal cancer Dòmhnall is determined to take her back to Abhainn nan Croise so she can die there, surrounded by her precious memories.

After much opposition the other members of the family agree to go, but on arrival they find they are no longer welcome. The situation descends into violence and bitter recrimination.

Lorn wrote the novel because of his veneration of tinkers, and the fascination he has for them from his earlier years at Connel where they came each year to a stance at Kilmaronaig.

Actions of the ‘lawless few’

While he does not romanticise tinkers in his novel – one of the characters is a persistent lawbreaker – he feels many people have judged them by the actions of the lawless few.

That continues to this day where, in places it’s been proposed to establish permanent sites with modern facilities, there has been angry opposition.

“Little wonder tinkers who have moved into permanent housing don’t declare their origins for fear of reprisals,” adds Lorn, “as I discovered while researching a programme for Gaelic television.

“We have forced tinkers to deny their identities because, as one woman residing in the city told me: “If my husband knew I was of tinker stock he would leave me.”

Lorn Macintyre’s life story

Born in Taynuilt, Lorn went to school in Oban. But he didn’t like school much.

Feeling overshadowed by his “very clever elder brother” who went on to become an internationally renowned mathematician, Lorn left school at 16.

With an aptitude for poetry and English, he worked as a trainee reporter at the Oban Times for 18 months.

When the new university of Stirling opened in 1967, he became the first Scottish student to be matriculated without any formal qualifications – instead receiving letters of recommendation from people like Norman MacCaig and Edwin Morgan because of the poetry he’d published.

Gaining a first class degree in English, and also meeting his wife Mary who has been the “greatest support and a discerning critic” of his work, he did teacher training then got a scholarship at Glasgow University for advanced study in the arts.

This was followed by a spell as head of English at Merchiston Castle boys’ boarding school.

In the 1980s, however, Lorn turned his attention to the then copious freelance media work available – writing for the likes of the Herald, Scotsman and Scots magazine.

He went from there to the BBC and worked as a senior researcher and script writer for Scottish cultural programmes.

It was a “strenuous job” which he enjoyed thoroughly as it gave him the opportunity to be extremely creative.

But it was also a time which generated more material for his now tinkers book.

“The interesting thing about the BBC is that I was in the Gaelic department,” he says.

“You would meet people from Lewis, Harris and other islands who had stories about tinkers and Travellers.

“I was absorbing a lot of this material – a lot of anecdotes – filled in with my own experiences.

“I learned a lot not just about tinkers and travellers but I learned huge amount about the history and culture of the Highlands and Islands. Some of the stories one was told were quite remarkable.”

A 20 year wait

Lorn, who retired to St Andrews with his wife in 2004, actually wrote The Summer Stance 20 years ago.

He takes what he admits is a “very peculiar position” with regards writing in that when he finishes a novel he doesn’t publish it straight away. He prefers to come back to it a few years later and revise it.

In fact, in his study he has 10 completed, yet unpublished, novels which he one day plans to bequeath to a library.

There’s another related area that fascinates Lorn and has done so since childhood.

He comes from a family of people who claim to have had “second sight”. For example, his aunt could tell when a healthy person was going to die.

He remembers his father – an extremely clever and cultured man – telling him about the day, in his bank manager’s office in Tobermory, a woman with second sight said her brother had drowned when his dreadnought was sunk in 1916.

“She told him that he came into the house the next evening with his kit bag on his shoulder and he’d been sitting in his chair ever since and it was a great comfort to her,” says Lorn.

“Because people knew of the Macintyre family’s own experiences, they would ask my father if this was a gift or a curse. They wanted to know why they could see these things.

“This shaded off in to me the tinkers some of whom had the same gift but didn’t have any sense of malevolence.”

A fading culture

Lorn says ‘second sight’ has almost ‘disappeared’ now because the world has become such a ‘noisy’ place with mobile phones etc.

Yet these talents, and their links to tinkers, are such an important part of Scottish heritage.

“If you think about the tinkers,” adds Lorn, “in early mornings leaving their camp with their cart and horses, they moved so quietly through the countryside that they would see aspects of nature that other people would not see ever see again.

“There’s one famous case – Willie Stewart the tinker – the family came round the bend and saw a car being rocked and a man sitting in it terrified.

“This car was being attacked by a pack of stoats that seemed to have gone crazy.

“It’s an exceptionally rare thing to happen.

“This takes me back to The Summer Stance because I tried to show through this character Donald that he’s trying to fight for the countryside to preserve it as it was when his grandmother was a young woman going out to the sites. These tinkers had a wonderful knowledge of the countryside and most of it has been lost.”

The likes of the late Hamish Henderson and the School of Scottish Studies in Edinburgh have done a lot to preserve tinkers stories and songs.

But Lorn is also conscious that lost elements of Scottish environment and culture are recorded in other works like those of Robert Burns.

*The Summer Stance by Lorn Macintyre is available from bookshops priced £7.99.