Jack Harland’s third book in a series about his passion for nature and hillwalking in the Highlands has just been published. Gayle Ritchie chats to the author and artist.

Jack Harland is drawn to the wilderness – to moments of silence, to the sound of running water, to the gentle rustle of wind through the trees, to the singing of birds in the mountains.

“I’m not a religious person,” he muses. “But it’s in these wild places that I feel close to something much bigger than all of humanity’s often sad and petty preoccupations. I feel free and at peace.”

After studying geography at Dundee University in the 1970s, Jack taught the subject and his love of exploring the great outdoors was forced to take a back seat.

His hillwalking and climbing dreams couldn’t compete with the demands of building a career and being a father to four children, so for many years his hiking boots sat gathering dust.

It was only when he retired as head teacher from Bridge of Don Academy in 2013 that he was able to indulge his passion, completing his final Munro, Stob Coire an Laoigh in the Grey Corries, in 2015.

Retirement also gave him more time to paint, draw, make maps and write, all of which led to the publication of his first book in 2018 – Highland Journal 1: The Making of a Hillwalker – an illustrated memoir looking back on his adventures.

The book detailed Jack’s introduction to hillwalking on family holidays to Polbain, north of Ullapool, and went on to look at his transition from wide-eyed novice to competent mountaineer.

A second book, Highland Journal 2: In My Stride, followed in 2019.

Now Jack has written a third book, Highland Journal 3: Beyond the Last Munro, published on May 28.

Some chapters record days of high adventure, such as the crossing of the Carn Mor Dearg Arête in Lochaber, but there are gentler days in Angus, Wester Ross and Assynt – days when the focus is on the author’s passion for the rocks, plant life and wild creatures of the Highlands.

“The inspiration for Highland Journal 3 was the same as for the others – a deep love of Scotland’s wild places and a desire to share this with others,” says Jack, 69.

“I loved my days on the hills so much I began to fill notebooks with a record of each day, plus maps and sketches. Family and friends read them and kept saying I should turn them into a book.

“I had to wait until I was retired, however, as I had so little free time.

“I did some calculations and realised that I’d need three books to do it justice.”

In Jack’s third book – the book in which he climbs his final Munro – he makes the point that “Munro-bagging” is not the be-all-and-end-all.

“I get as much pleasure from days exploring little-known hills in quiet corners of our lovely country as from days on the big ones,” he reflects.

“It’s called Beyond the Last Munro because I wanted to make it clear that my books about the Highlands are not just a record of climbing Munros.

“There’s so much more out there to explore and enjoy, often superior in many ways to the Munros.”

But Jack did, of course, scale all 282 Munros, spurred on by pals.

“When I realised I’d climbed 100 I decided I’d better climb the rest!

“Towards the end, climbing mountains just because they were classified as Munros became irksome at times and it was with something of a grim determination that I set off to climb the last ten or so.

“On the last one I felt a great sense of relief and knew that I then had a new freedom to go wherever I wanted.”

It was the Scouts that first introduced Jack to Scotland’s mountains, finding himself thrilled by what he saw as a new and mysterious world, exploring windy ridges and climbing scree-laden hills during summer camps.

During his time at Dundee University, he spent weekends exploring the Angus Glens with one of his lecturers.

“I love the hills around Glen Clova, Doll, Esk and Shee and regard them as my ‘Hills of Home’,” he says.

“My family say that one day, when I’m ancient, I’ll die up there on Jock’s Road.

“I always reply that I relish the prospect. No lingering in a nursing home for me.”

Over the decades, Jack has found himself drawn to the striking wilderness of Assynt, and returns there often.

“As I drive down the mad road past Stac Pollaidh I always feel the same – that this extraordinary landscape is so much better than Alpine scenery.

“Understanding something of the equally extraordinary geology certainly gives a depth to my appreciation and the mountain plant and animal life fascinates me.

“But it’s the wilderness that draws me. I’ve lived such a busy life, filled with people, and however wonderful they were, I value my days of escape and peace. On many days in the mountains I see no-one at all.”

“My family say that one day, when I’m ancient, I’ll die up there on Jock’s Road. I always reply that I relish the prospect. No lingering in a nursing home for me.”

Jack Harland

While Jack is accompanied on expeditions by various people, his longest-term hillwalking buddy is his son, Tom, who he describes as a “kindred spirit”.

An old soldier and member of the Cairngorm Club, James Murray, comes with him on many walks, as do two of his grandsons and the Jolly Boys, a fun hillwalking group.

The third book has highlights, and of course a few hairy moments, but Jack says there are no low points.

“Crossing the Carn Mor Dearg Arête; climbing Ben More the hard way with the Jolly Boys; being with my grandsons when they climbed their first Munro; walking on the North Harris Hills; being on the snow-covered Sgurr nan Ceathreamhnan on a perfect day with my son; every moment in the Fisherfield and Letterewe wilderness; the day on Breabag, Assynt, when I saw the mountain water vole; spending time with an adder on Hunt Hill – these were major highlights,” he muses.

“There were often challenging moments and the book has its fill of sheer drops, crossing flooded rivers, attacks by fierce hordes of midges and, worse than cold by a long, long way, climbing in heat that makes every step torture.

“But the thing I worried about most was getting the ropes right as I helped get a casualty lifted up into a rescue helicopter on Beinn Narnain.”

Jack’s latest book sees him heading to the islands of Mull and Harris, exploring the lonely moors of Sutherland, the Rough Bounds and the Great Wilderness.

“Mull has always fascinated me because of its complex geology and the way that it is so easy to see and understand there; the very bones of the land are exposed,” he says.

“Harris is weirder, and we’ve had some memorable family holidays there, in a little cottage perched on the edge of a low cliff above the sea.

“The mix of mountain, sea, lochan and sea loch make this a very special landscape, one where it is difficult to see where the water ends and the land begins.

“The skies are often fantastic and the soft light has a quality I’ve seen nowhere else.”

Anyone who’s explored Glen Carron may well have driven past or stayed at Gerry’s Hostel, around 3km east of Achnashallach Station.

It was here that Jack became friends with the man himself, describing Gerry as a legend among hillwalkers.

“He was very much a Marmite character, some hating him and he hating them back!” he laughs.

“I hit it off with him (with the help of a good malt whisky) and dreamily danced the evenings away to his collection of 1930s jazz records, the flickering flames of the fire lighting the peculiar sitting room. I was sad to hear of his death a few months later.”

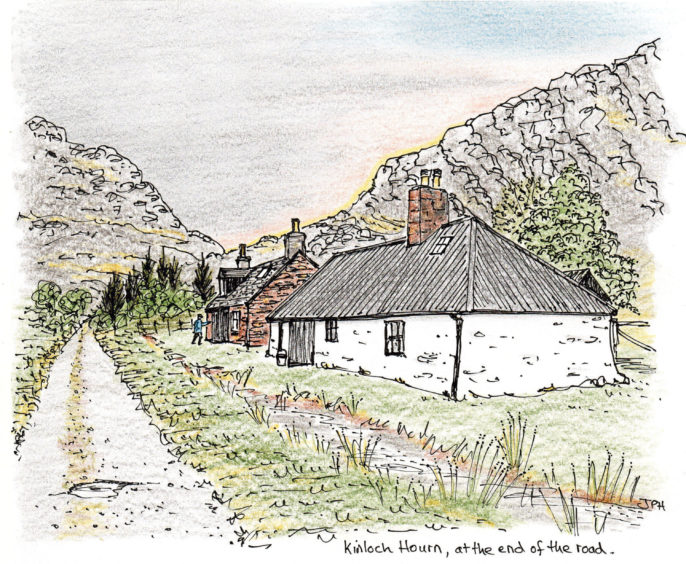

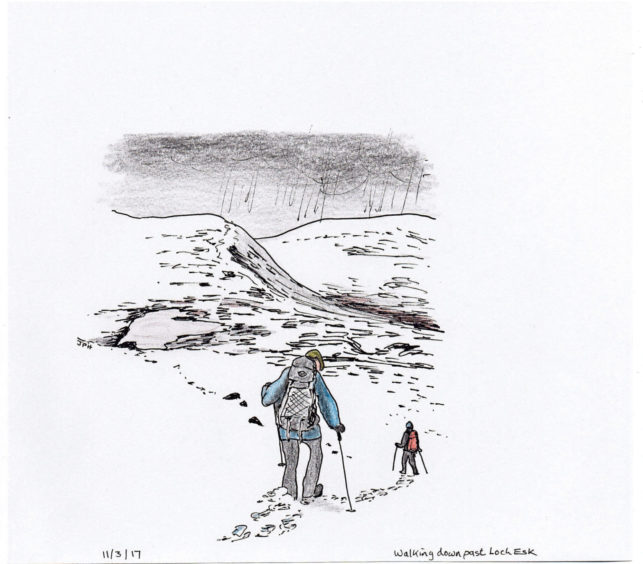

Jack’s stunning illustrations, featured in his books, begin as rough sketches drawn into his notebook when he’s in the mountains: “I find photos invariably diminish things and sketches are so much more evocative of particular walks, creating memories that really stand the test of time.”

When asked what his favourite walk is, Jack hesitates – there are too many to choose from.

But he says Ben Avon and Beinn a’ Bhuird in the Cairngorms are hard to beat.

“It’s a big day to climb them both, as they are so far from the road and partly because of that they are often devoid of people.

“I love the massive bulk of these granite mountains, the wild storms that rip across them, the exposed granite tors that create such an alien landscape and the huge skies.”

While excited about the release of Highland Journal 3, Jack has other irons in the fire.

He’s written the first version of an illustrated children’s book called Little Dog and Tiger, is writing a book about climbing the hills he sees from the window of his home in Peebles and has plans for an illustrated book about Dundee.

*Highland Journal 3: Beyond the Last Munro by Jack Harland is published by Troubador, priced £15.99.