Professor Sir Philip Cohen is among the most honoured scientists in the UK, having received nine awards worldwide. As he celebrates 50 years of working for the University of Dundee with the launch of a new charity to support PhD students, we look back at his illustrious career.

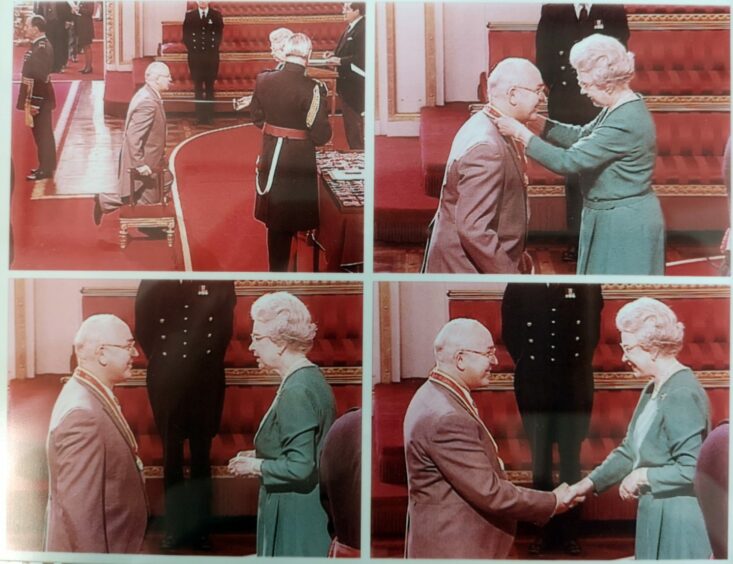

To be knighted by the Queen for your contribution to medical science through your work is a pretty special achievement.

But Professor Sir Philip Cohen, a researcher in life science at the University of Dundee, took it in his stride when he received the honour in 1998.

Sir Philip’s knighthood was presented in recognition of his work building up the university’s Life Sciences research department into a ‘major powerhouse’ in its field.

And through that, creating the foundations of the biotechnology industry in Dundee, which now accounts for around 10-12% of jobs in the city.

Sir Philip, 76, says the moment the Queen shook his hand was undeniably a highlight in his personal life, describing the event as ‘marvellous’.

He said: “We [research team] had been doing a lot for science in the city but we didn’t realise it for a long time because we had been making many small, incremental advances.

“Then the research got to the stage where we could see what we had put together was amazing and that we had built up a new industry for Dundee.”

And that was something which meant a great deal to Sir Philip, having relocated to Dundee from Seattle, in Washington, when he was 26 years old and the city’s jute industry had been recently lost.

However Sir Philip describes his discovery two years prior to the Queen’s recognition as the true highlight of his scientific career – when he worked out how insulin works in the body.

It took Sir Philip 25 years to solve the scientific problem, reading vast amounts of literature and carrying out experiments, 95% of which ‘go wrong’ he says.

He said: “It’s not a eureka moment, it’s gained in small discoveries then suddenly you get to the stage when the last pieces of the jigsaw fall into place.

“You have to read literature widely, remember everything which you have read, research the problem and have an understanding of how the system works.

“Then you have to design experiments to solve the problem and that goes on for about 25 years before you finally get to the stage of finding out how it works.”

Through this work Sir Philip discovered new enzymes – proteins within cells – called kinases, which have since been targeted by pharmaceutical companies to create around 75 drugs to treat illnesses, mainly cancer.

And in 1998 Sir Philip set up the world’s largest collaboration of academics and the pharmaceutical industry, called the Division of Signal Transduction Therapy, which helped stimulate the biotech industry further.

He said: “What you find sometimes doesn’t turn out to be useful for what you thought, but useful for something else and the outcome can be very different from what you expect.

“That’s one of the exciting things about research. I’m still discovering interesting things.”

After resolving how insulin worked, Sir Philip’s interest turned to understanding the innate immune system, our body’s first defence in fighting off new infection which it has not encountered before.

Not to be confused with the adaptive immune system, which knows from memory how to fight off infection the body has been exposed to before or through vaccine.

Sir Philip said: “The innate immune system has no memory and produces interferons to fight off a new virus, such as Covid-19.

“How these interferons are made is not clear and we’re still trying to work that out.

“Interferons were discovered in 1957 but how they work, that is what is still under investigation and it would help us enormously if we could.

“Recently it has become increasingly competitive, which is good because it means we will get a solution faster.”

Understanding how the innate immune system works could lead to ways of controlling it, boosting underactive systems and dampening overactive ones which can lead to conditions such as asthma, arthritis and Crohn’s.

Sir Philip also hopes to discover through his work, funded by the Wellcome Trust and Medical Research Council, why some people cannot make interferons, making them more susceptible to infection.

And despite his age, Sir Philip says he will continue his work as long as it is funded, saying his concentration has improved with age and his experience is invaluable.

Over the years he has published more than 600 research papers and received nine awards worldwide, between 1993 and 2014 – the most recent being the Albert Einstein World Award of Science.

Having been the first employee to join Professor Peter Garland at the university’s then biochemistry department in 1971, Sir Philip helped the department grow dramatically.

Now the Life Sciences research complex is home to over 800 scientists and staff and Sir Philip has mentored countless young researchers and more than 100 PhD students and postdoctoral scientists.

I’m still discovering interesting things.”

Sir Philip Cohen

Sir Philip is now looking to encourage the next generation of researchers with the launch of a charity to support PhD scholarships, in memory of his late wife Tricia, who was also a biochemist.

The Tricia Cohen Memorial Fund will fund six PhD Studentships that will run consecutively from 2022 until 2044, the year in which Tricia would have reached the age of 100.

Together with their two grown-up children, Suzanne and Simon, Sir Philip has launched the trust in Tricia’s name one year after she passed away, on his 50th work anniversary.

He said: “I am delighted to have reached the half century at Dundee and to have witnessed and been part of the remarkable growth we have seen in life sciences here.”

Donations to the Tricia Cohen Memorial Trust can be made through the website.