A university professor and former Bishop has said schools should teach Christianity as part of history rather than confining it to religious studies.

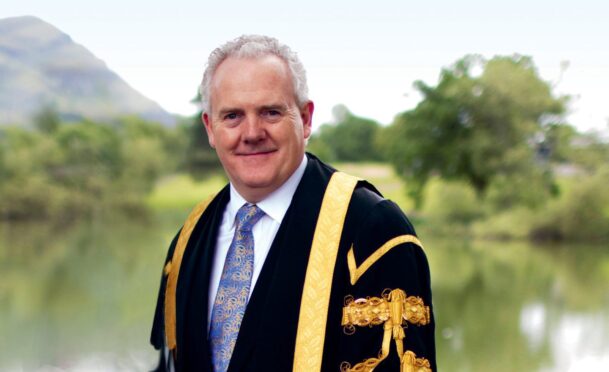

Tom Wright, professor of New Testament and early Christianity at St Andrews University, said the story of how Christianity “got going” in the western world should be taught in a “historical context”.

The former Bishop of Durham fears the teaching of Christianity’s influence on the western world was being “restricted” to religious studies class.

The Humanist Society in Scotland responded to the professor’s comments by saying children “do not suffer” by not being taught Christianity in their history class.

Meanwhile, Scotland’s largest teaching union, Educational institute Scotland, said a “wide ranging” religious education was taught in schools.

Professor Wright said: “If a pupil wanted to study Jesus in his historical context, this would not be seen as part of the general history syllabus, but would be something that was the preserve of religious studies.

“Religious studies staff would then say they had Judaism, Buddhism and Confucius, as well as Christianity, and maybe there would be something on the Gospels in the corner.

“It seems to me, in terms of the history of the western world, the narrative of how Christianity got going and who Jesus was are huge questions that ought to be in a more general syllabus.”

He continued: “The fear I have is that questions about the Gospels and Jesus seem to be restricted to a few parables and the Crucifixion rather than being seen as events that changed the world, whether you agree with them or not.

“Religion tends to get shunted to the side and this systematically distorts the world in which we live, which has been so radically shaped by the Christian tradition.

“To not know about that is to condemn the next generation to almost ignorance of part of the scaffolding of the house in which we westerners live.”

Gordon Macrae, chief executive of the Humanist Society in Scotland, said: “I’m sure most people in Scotland can agree Christianity had a profound effect on shaping modern Scottish culture, but we are now at a tipping point where a majority here are not religious.

“I can’t help but feel certain the largely irreligious children do not suffer for a lack of religion in their education, quite the opposite.”

Larry Flanagan, general secretary of the Educational Institute of Scotland, said: “Religious education in Scottish schools takes a wide-ranging view to offer pupils a deeper understanding of the role of religion across the globe.

“Schools are already buckling under competing demands for inclusion in the syllabus and teachers must be allowed some professional autonomy.”