As the 137th anniversary of the Tay Bridge disaster approaches, and ahead of a talk in Dundee, local expert Professor David Swinfen tells Michael Alexander why new light is being shed on the cause of the disaster.

When the Tay Bridge was completed in 1878 after taking six years to build, it was one of the longest bridges in the world.

Famous visitors including the Emperor of Brazil, Prince Leopold of the Belgians and Queen Victoria herself came to pay homage to this marvel of Victorian engineering.

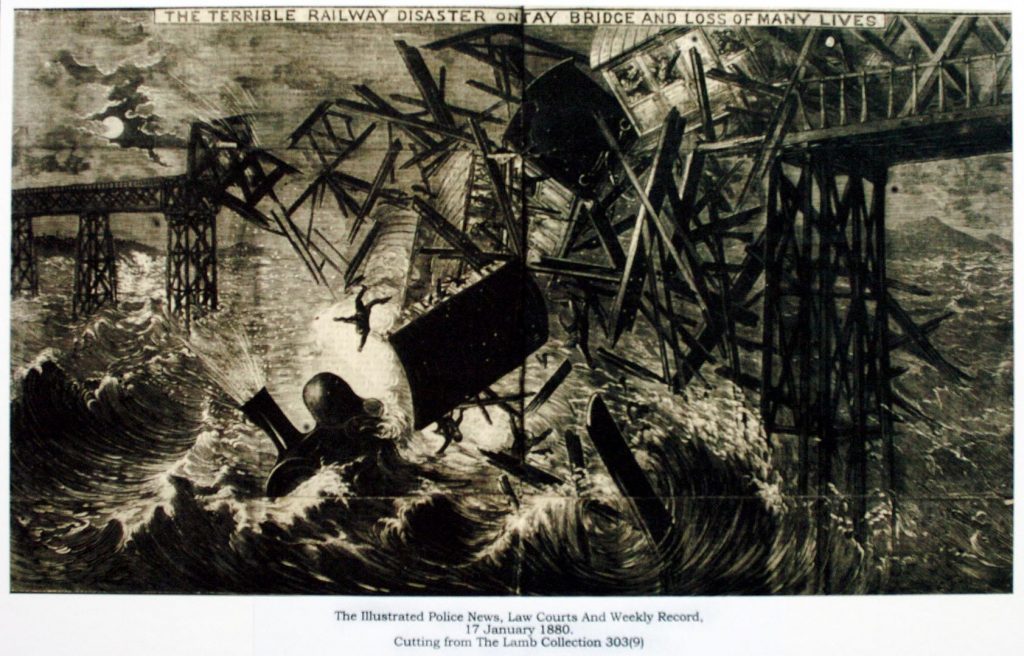

But on the night of December 28, 1879, the unthinkable happened.

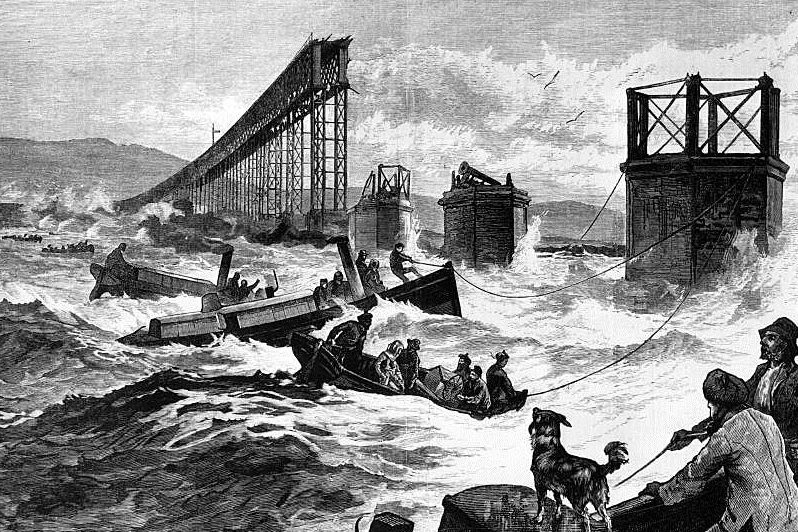

Battered by a ferocious storm, the 13 ‘high girders’ of the rail bridge over the Tay estuary collapsed into the river below, carrying with them a train and all its passengers and crew. There were no survivors.

There has been much debate over the years on what caused the fall of the Tay Bridge and who was really to blame.

The Board of Inquiry concluded that a combination of design failures, construction and maintenance were at fault, with renowned engineer Sir Thomas Bouch officially blamed.

Now, ahead of an illustrated talk he is giving at Dundee Transport Museum on December 10, retired Dundee University history professor David Swinfen – author of revised and updated book ‘The Fall of the Tay Bridge’ – has analysed new evidence about the number of lives lost and presents a solution to what he believes really brought the bridge down.

As chairman of the Tay Bridge Memorial Trust, his interest was rekindled four years ago whilst researching what names should be put on the memorials since erected at either side of the bridge.

“The figure most often cited is 75 dead – and this figure was accepted by the Court of Inquiry, “Professor Swinfen, 80, of Broughty Ferry, said.

“On the other hand we only know for certain that 59 people were lost, in the sense that we only have death certificates for 59.

“The reason why there is a discrepancy is that there are two different ways in arriving at the conclusion.

“The figure of 75 ultimately comes from the Court of Inquiry. That’s the figure that they accepted.

“The reason they accepted it was because they were given information by staff at St Fort Station, which was the last station before the bridge, and that was where they collected tickets for passengers going to Dundee.

“They collected 56 tickets. On top of that there were people with season tickets, people going on beyond Dundee who had their tickets checked on a list but were not actually taken.

“But the fact is we cannot prove there were 75. We can prove there were 59 because we have documentary proof.”

Professor Swinfen says debate surrounding the reasons for the collapse is more complicated.

One argument is that the train itself crashed into the bridge and brought it down.

Others say the bridge fell down and took the bridge with it.

“Ever since John Prebble produced his seminal ‘High Girders’ book, indeed even well before that, there has been a vigorous debate about the causes of the disaster, and the allocation of blame,” continued Professor Swinfen.

“Going back to the original Court of Inquiry in 1879/80, it was concluded that the fall was due to faults of design, construction and maintenance, for which Thomas Bouch was principally, of not exclusively, to blame.

“Amongst more recent accounts, explanations broadly speaking fall into one of two categories – either the bridge was brought down by the train, or the train was brought down by the bridge.

“In the first category we find Bouch himself. He was convinced that a second class carriage had come off the track, caught on the side girder, and ripped the bridge apart.

“In recent years this explanation has been accepted by a number of writers, especially with reference to the so-called ‘kink in the rail’ – a distortion of the track which, it is claimed, caused the carriage to become derailed.

“Against that, there is the argument that the bridge simply blew down, taking the train with it.

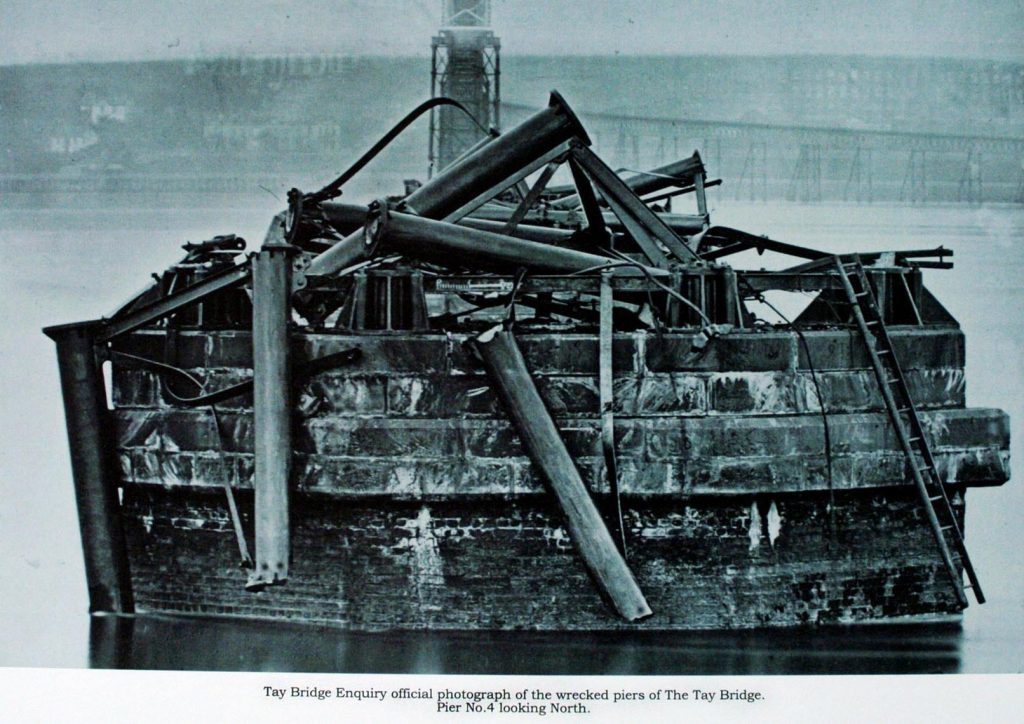

“What is common ground is that what actually failed were the ‘lugs’ cast integral with the columns.

“These were protuberances with a hole through them to which were attached wrought iron tie bars, by means of nuts and bolts, just like a giant Meccano set.

“These tie bars connected the six cast iron columns together to make each of the towers supporting the track.

“One recent contribution to the debate has alleged that over the life of the bridge the passage of trains induced metal fatigue in these lugs, causing them to fail.”

In the original version of Professor Swinfen’s book, published in 1994, he accepted the argument that the bridge blew down, and that there had been insufficient allowance in the design for wind pressure.

He also drew attention to another crucial fact – that the holes cast in the lugs, being conical in shape rather than cylindrical, meant that excessive stress was exerted on them by the force of the wind. These facts explained the failure of the lugs in the conditions of the fateful night.

In the revised version of his book, he has reviewed all the popular explanations, especially in the light of recent articles in civil engineering journals.

“My conclusion from all this is that my original explanation of the fall was largely correct, but with some important additions and modifications,” he added.

“In light of the journal articles, and of the expert opinion of leading civil engineers, I have rejected the claim that metal fatigue was a factor in the collapse.

“I have drawn particular attention to the fact that the connecting bolts through the lugs were thinner than they should have been, with the consequence that the stress was concentrated on the point where the bolt touched the inside of the hole.

“I have also discovered that the specification of the thinner bolts by Bouch was a cost cutting measure, as was his decision to substitute the cast iron lugs for the much superior method of connecting the columns used in the Belah Viaduct by the same designer.

“If only he had used this method, perhaps the disaster might have been avoided.

“All this has persuaded me to arrive at a much more critical judgement of Bouch than in the original version.”

- The Fall of the Tay Bridge, by Professor David Swinfen, is published by Birlinn, priced £10.99.

- Professor Swinfen speaks at Dundee Transport Museum at 3pm on December 10. For more information go to dmoft.co.uk