Forty years ago, Gunpei Yokoi, a product engineer for Nintendo, sat on a commuter train in Kyoto and watched a fellow passenger idly while away the journey by playing with the buttons on a pocket calculator.

As he looked on, Yokoi became convinced that he could take the same LCD technology that powered the calculator, and rework it, creating a graphical interface by reshaping the display segments and designing a simple – but very playable – game around it. The result was Ball, the first in Nintendo’s popular Game and Watch series, and a direct ancestor of the Game Boy.

Yokoi’s design philosophy was one he called ‘lateral thinking with withered technology’. He would take cheap, well-understood technologies and try to imagine how they might be used in novel and innovative ways. By reconceptualising the pocket calculator, Yokoi created a new, portable form of electronic play.

Fifteen years later, Oliver Wittchow was a design student at the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg. As he was preparing for his final-year project, he found his brother’s old Game Boy and did exactly the same thing. Wittchow looked beyond the slab-sided plastic case of the plug-‘n’-play console and saw something nobody else did: a primitive, but very characterful handheld synthesizer.

Wittchow spent months learning to code, hacking his Game Boy as he went along. By the spring of 1998 he had a working prototype, which he entered at a lo-fi music contest at the Liquid Sky club in Cologne. On the night of the competition, he was nursing a heavy cold, and he remembers his software glitching almost to the point of collapse, but the crowd loved it. They loved the sound and they loved seeing a familiar toy reimagined as a musical instrument. Spiritually, Wittchow was applying Yokoi’s philosophy and breathing new life into a tired old platform.

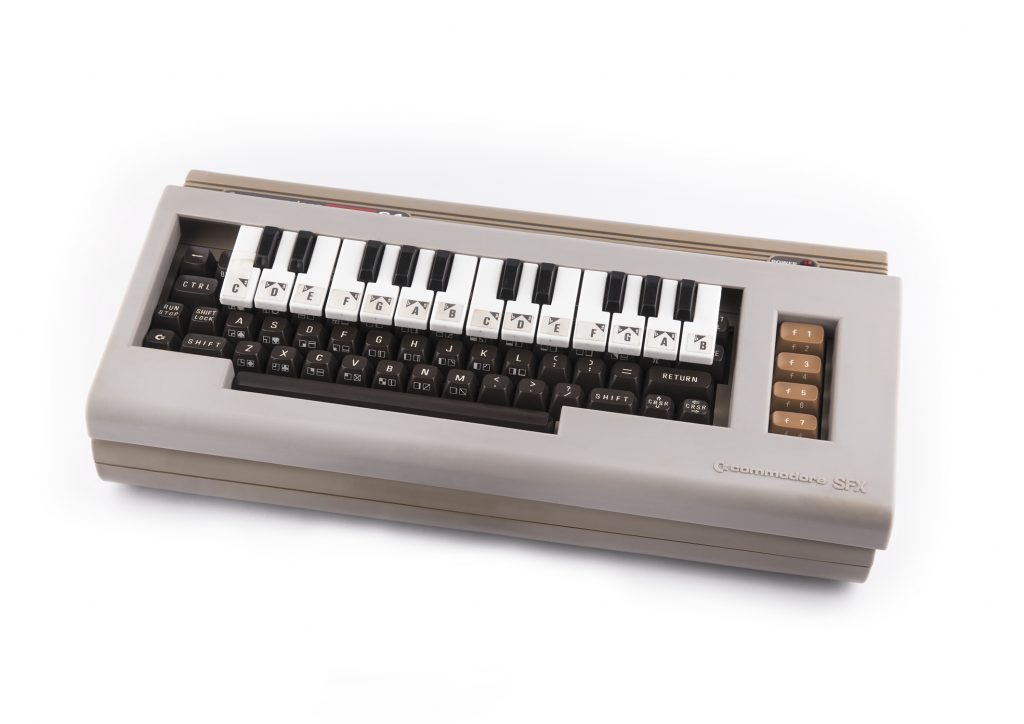

This is the spirit of chiptune, a vibrant culture of lo-fi electronic music production and performance that grew out of the first generation of video game consoles and home computers. It’s not so much a style as it is an approach to music-making. Instantly recognisable, it has a cheery, blippy sound that will be familiar to anyone who grew up playing ZX Spectrums and Commodore 64s in the early 1980s.

But chiptune isn’t recycled video game music, and it’s not something that has only nostalgic appeal. Chiptune musicians, many of them too young to have been born when that first generation of hardware was already obsolete, hack vintage devices and reimagine them as musical instruments, in the process giving that 8-bit sound a very contemporary edge. It’s the sound of techno-counterculture, of geek rebellion.

That sound is loaded with positive association and fun. The Game Boy musician, DJ Scotch Egg, for example, opened his set at the Boiler Room in Berlin in May 2014 dressed in a floral apron, and broke off from performance to flip pancakes, while Sonic Death Rabbit, a chip fusion two-piece, use Game Boys alongside toy guitars, turntables, and screaming death metal guitar, to construct performances that rely as much on the audience’s understanding of the cultural weight of the toys and games they use as it does the sounds they create.

But there is another very positive aspect to all of this. All of a sudden, games consoles that had been obsolete, worthless piles of junk become characterful musical instruments that make a hip, retro statement. Chris Mylrea, for example, an Australian musician, wired up an Atari VCS to some effects pedals on a guitar-styled body and started gigging with what has become known as the gAtari, which is surely crying out for a cover of the Beatles’ classic, While My gAtari Gently Beeps…

Such inventive recycling of hardware is a refreshing counterpoint to the relentless drive of technological progress. Users might drift to new hardware that boasts more memory, faster processors and better sound, but, by looking at these machines from a different perspective, we can recast and reinvigorate them. Technology is only as useful as we make it. Chiptune shows us that there is, indeed, many a fine tune played on an old fiddle.

Dr Kenny McAlpine is Academic Curriculum Manager at Abertay University’s School of Arts, Media and Computer Games.

This column is supported by UNESCO, City of Design Dundee.