It was a time of heightened superstition in Fife’s maritime communities.

With the majority of people engaged in the dangerous occupation of seaborne trade and fishing, life was precarious and uncertain during the 17th and early 18th centuries, and this served to heighten the community’s sense of religion and superstition.

It’s no coincidence then that the majority of Scotland’s ‘witch’ persecution cases took place in coastal communities like Torryburn in south-west Fife where, in 1704, they had what was perceived to be a ‘toxic witch problem’.

Lilias Adie, a poor woman who confessed to being a ‘witch’ and having sex with the devil, died in prison before she could be tried, sentenced and burned.

So they buried her deep in the sticky, sopping wet mud of the foreshore – between the high tide and low tide mark – and they put a heavy flat stone over her amid fears she would come back to haunt them.

Now, for the first time, the face of Lilias Adie has been scientifically brought to life thanks to work carried out with a forensic artist at the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification at Dundee University.

The image is being showcased for a Halloween special of BBC Radio Scotland’s Time Travels programme which broadcasts today (TUESDAY) at 1.30pm.

It is likely to be the only accurate likeness of an actual Scottish ‘witch’ from times past in existence, as most were burned, destroying any hope of reconstructing their faces from skulls.

Lilias lay at rest beneath the foreshore for more than a century.

However, by the 19th century, scientific curiosity outweighed zombie fears and some antiquarians dug up Lilias to study and display.

Their biggest prize, her skull, eventually went to St Andrews University Museum, where it was photographed more than 100 years ago.

The skull itself however went mysteriously missing at some point in the 20th century, but the photographs remain and are held by the National Library of Scotland.

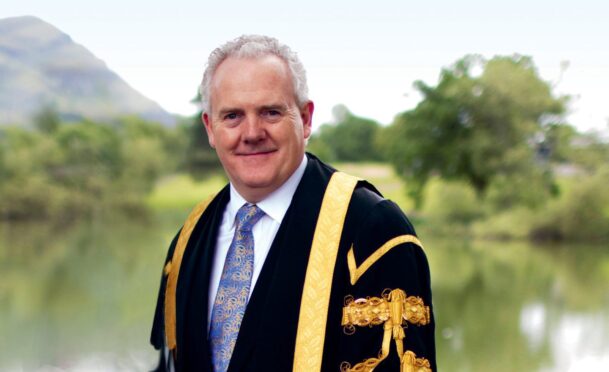

Time Travel’s presenter Susan Morrison, working with the programme’s historian Louise Yeoman, wondered if it would be possible to make a digital reconstruction of her face from the photographs alone.

The skull, with haunting eye sockets and strikingly prominent buck teeth, virtually promised to deliver a classic witchy face.

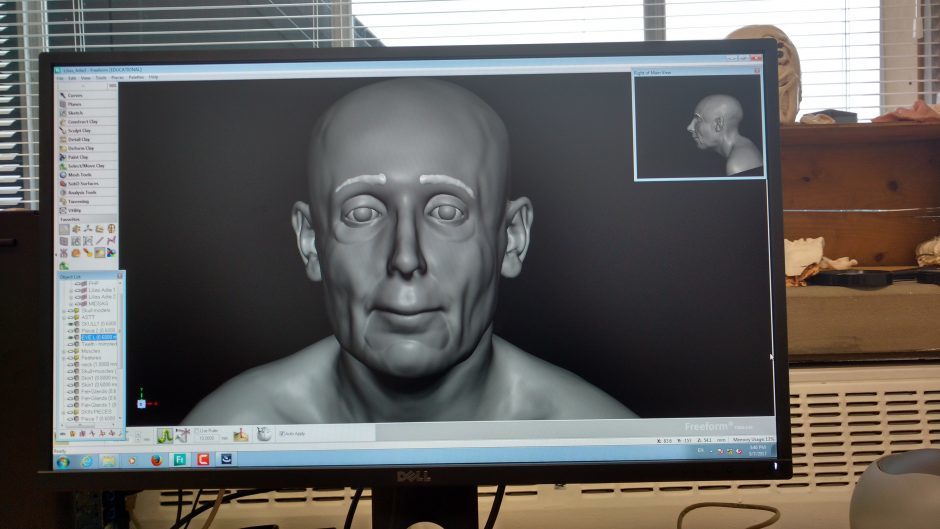

But Dr Christopher Rynn, who carried out the work using state-of-the-art 3D virtual sculpture (Geomagic Freeform) in conjunction with forensic facial reconstruction methods, produced a somewhat different picture of Lilias.

He said: “The process is step-by-step anatomical interpretation: sculpting musculature and estimating features (eyes, nose, mouth, ears) individually from the skull, so it’s not as though you could look at a skull and instantly see the face: you have to reconstruct it to visualise it.

“When the reconstruction is up to the skin layer, it’s a bit like meeting somebody, and they begin to remind you of people you know, as you’re tweaking the facial expression and adding photographic textures.

“There aren’t really any artistic decisions to make until the very end, such as facial expression. Even though the upper teeth are indeed prominent, it doesn’t necessarily follow that she would have ‘incompetent lips’ (i.e. mouth hanging open): most people with an overbite tend to hold their mouth closed, giving a distinctive shape to the lips and chin.

“Either way, there was nothing in Lilias’ story that suggested to me that nowadays she would be considered as anything other than a victim of horrible circumstances, so I saw no reason to pull the face into an unpleasant or mean expression and she ended up having quite a kind face, quite naturally.”

The records of her accusers paint a picture of a woman, possibly in her 60s, who may have been frail for some time, with failing eyesight.

But they also suggest a woman, who showed immense courage in holding off her accusers and their Historian Louise Yeoman said: “I think she was a very clever and inventive person. The point of the interrogation and its cruelties was to get names.

“But Lilias said that she couldn’t give the names of other women at the witches’ gatherings as they were masked like gentlewomen.

“She only gave names which were already known and kept up coming up with good reasons for not identifying other women for this horrendous treatment…despite the fact it would probably mean there was no let up for her.”

This project is a follow-up to another a previous collaboration between the Radio Scotland History team with Fife archaeologist Douglas Speirs three years ago, which identified the likely spot on the Torry coastline for Lilias’ grave

Local records from the 19th Century, written after the grave robbing, mentioned “the great stone doorstep that lies over the rifled grave of Lilly Eadie “ (sic) on the foreshore at Torry.

Douglas was able to confirm the stone slab was not natural to the beach, but had been quarried and deliberately placed there. The slab has a dimple in its middle, which may have assumed to be the socket for an iron ring.

A short clip of the digital reconstruction, as well as Lilias’ face as she would likely have been in the times with a hair-covering, and as how she might have looked as an elderly woman in modern times, is available to view at https://www.bbc.co.uk/radioscotland