Five hundred years after the start of the Protestant Reformation in Germany, Michael Alexander examines the bloody role of St Andrews in the Scottish Reformation that followed and asks Scotland’s modern day Catholic and Protestant leaders what lessons can be learned from a tubulent past.

Five hundred years ago on October 31, 1517, an unknown monk called Martin Luther marched up to a church in Wittenberg, a small town in what is now eastern Germany, and nailed a list to its door which criticised some of the practices and doctrines of the late Medieval Roman Catholic church.

His list of criticisms, known as the 95 theses, protested against what he regarded as the “corrupt” sale of ‘indulgences’ – payments the church said reduced punishment for sins after death – which lit the fuse of what became the Protestant Reformation.

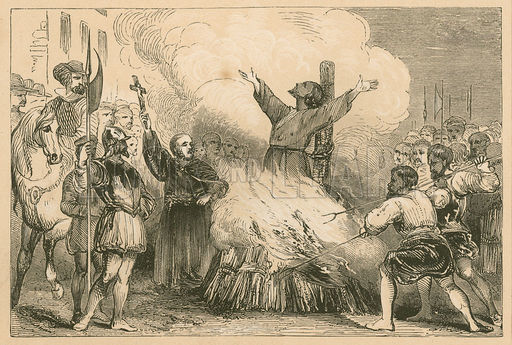

Reverberations across Europe ranged from a split in the church, the fighting of wars and the burning of people at the stake to the translation of the Bible into languages other than Latin and the expansion of literacy to those other than the wealthy.

In Scotland, it was ultimately the other founder of the European Reformation, the French theologian Jean Calvin who was to have the greatest influence in terms of theology, doctrines and forms of church government and polity.

However, the influence of Luther was also important with St Andrews laying claim to being the birthplace of the Scottish Reformation in 1560 with four early Reformers having been sentenced to death in the town for their beliefs.

The first was 24-year-old Patrick Hamilton who was burnt at the stake in North Street in 1527, after he promoted the doctrines of Martin Luther.

In the years that followed, Benedictine friar Henry Forrest was burned to death near St Andrews Cathedral in 1533 for owning a copy of the New Testament in English; George Wishart was burnt at the stake outside St Andrews Castle in 1546 for defying the Catholic Church and former Angus priest Walter Myln followed in 1558, having advocated married clergy.

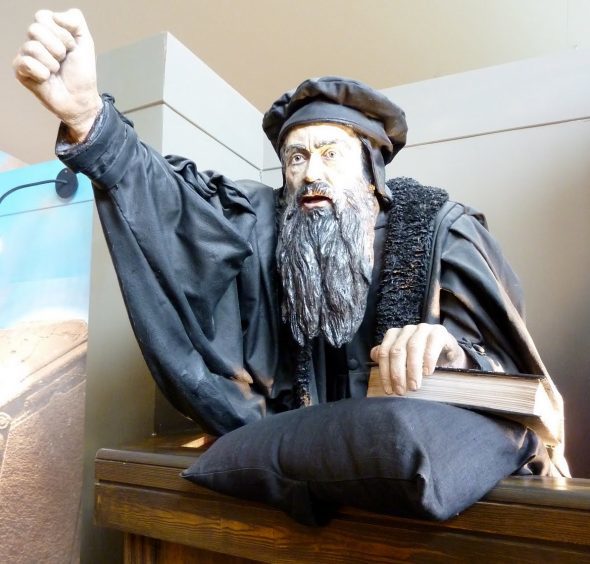

In the end their cause prevailed. In 1559, St Andrews Cathedral – which was Scotland’s largest church at the time- was sacked and desecrated by a mob following a famously fiery sermon preached in the town’s Holy Trinity Church by John Knox, and Scotland became officially Protestant a year later.

Today St Andrews, with its commemorative Martyrs Monument at The Scores, is the only place in the UK to be officially designated as a “City of the Reformation” by the Community of Protestant Churches in Europe.

But 500 years on, amid an increasingly secular society where, according to the 2011 UK census, 1.7 million Scots describe themselves as Church of Scotland and 841,000 describe themselves as Catholic, what lessons can be learned from the often violent events of five centuries ago?

A spokesperson for the Catholic Church told The Courier the time was right for a “sober analysis” of what was “lost and gained” during those turbulent times.

“When St. Andrews Cathedral was dedicated in 1318,” the spokesman said: “it was by far the largest church in Scotland.

“Two hundred and fifty years later in 1559, the Protestant reformer John Knox preached a famously fiery sermon against idolatry which resulted in the building being attacked and desecrated, the friars of the cathedral were “violently expelled” and the cathedral was subsequently abandoned and ruined.

“The Reformation left the town bereft of its cathedral and in many ways robbed Scotland of much of its cultural and spiritual patrimony.

“Five hundred years on we would benefit as a country from a sober analysis of what has been lost and gained as a result.”

The current Moderator of the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland, the Very Rev Dr Derek Browning, is a St Andrews University divinity graduate with a keen interest in history. He met Pope Francis for the first time in Rome last week and will be in Germany to commemorate the Reformation 500th anniversary.

While lessons can be learned from history, the Edinburgh-born former minister of Cupar Old Parish Church says it’s “not helpful” to impose 21st century ideas on 16th century people.

“I don’t know if anyone would come out of the 16th century particularly well!” he said.

However, what was most significant about the Reformation process in Scotland, he added, was that it reconnected people to the church, to political and social processes, to the Bible and, significantly allowed people to worship in their native language.

He said: “That was something that was particularly significant here in Scotland because alongside changes in the religious world, one of the key things the Scottish Reformers went on to do was ensure that as well as a church in every parish area there was also a school in every parish area – and that’s something we should be proud of in our country.”

Of course, not everything about the Reformation was positive. Retired Broughty Ferry minister the Rev John Cameron of St Andrews points out that John Knox was also responsible for the destruction of far more religious art than present-day ISIS and his 1563 Witchcraft Act led to the horrifying deaths of over 2000 innocent people before it’s repeal in 1736.

However, time is a great healer and, during their meeting last week, Pope Francis told Rev Browning it is a “great gift” that the Catholic Church is now able to live in “true fraternity” with the Church of Scotland in 2017. He told the Moderator the two denominations enjoyed a relationship of “mutual understanding, trust and cooperation”.

Rev Browning said it was “very significant” that in this day and age, the churches can honestly recognise that in spite of different opinions on certain matters, they are united by far more.

He added: “One of the significant things over a number of years now is the way in which Christians of all denominations, and actually people of faith from many different faith families, are beginning steadily to work very closely together on matters that we share in common.

“That will be around things like supporting people in poverty, speaking out on matters of social justice, being involved in matters related to homelessness and many other areas.

“One of the things I’ve been absolutely delighted to have been involved in in my year as Moderator so far are the many different occasions when people of all faiths have been able to get together.

He added: “It was clear to the Pope that the churches should not be seen now as being in rivalry with each other – we work together on so many different matters. That is very important to him and it’s certainly very important to me.”