St Andrews University Wardlaw Professor of Modern History Colin Kidd tells Michael Alexander why religion rather than UK identity has been the major influence on Scottish literature over the past 300 years.

They have been some of the most heated debates surrounding national identity of all time with debate about the future of the United Kingdom coming to a head with the Scottish independence referendum of 2014, and Brexit adding further debate to the constitutional direction of the UK since 2016.

But according to a leading St Andrews University academic, being part of the UK has not been as central to the identity of Scottish people over the past 300 years as some might think.

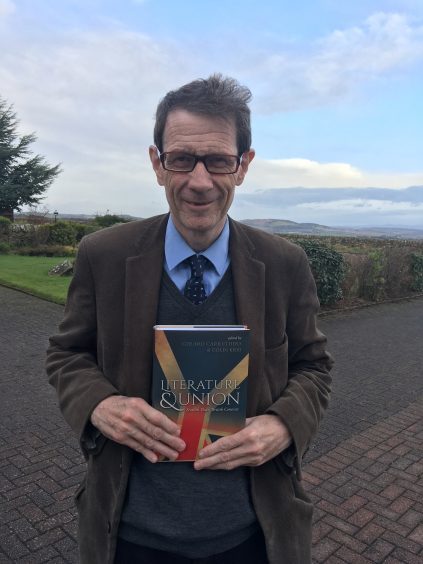

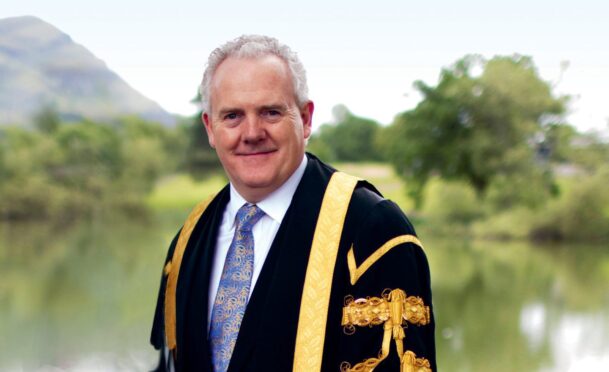

The conclusion has been reached by Colin Kidd, Wardlaw Professor of Modern History at St Andrews University and Fellow of All Souls College, Oxford, in a new book – co-edited with Glasgow University academic Gerard Carruthers – called Literature & Union: Scottish texts, British Contexts.

Professor Kidd, 53, argues that Scottish culture has been more influenced by religion than politics over the centuries and that Scottish nationalism has really only reared itself since the end of the Second World War when the majority of the population started “drifting away from the pews”.

“I can give you a very vivid example from the West of Scotland,” says Ayr-raised Professor Kidd in an interview with The Courier.

“If you go into railway stations or bus stations or toilets you’ll never see graffiti about 1707 – but you’ll see plenty about 1690 (the Battle of the Boyne)!

“If you go down to the pub, you very rarely hear people talking about 1707 – but 1690 has some resonance!

“That’s what I mean when I say it’s Protestantism, and religion and differences – not just between Protestants and Catholics, but also between Presbyterians and Episcopalians in Scotland that have been the dominant issue over the past 300 years.

“Really the Union has only come into focus to be the dominant issue in the last few decades – and that’s why if you look at the bulk of Scottish literature through the last few centuries, the Union is striking actually more by its absence than by its presence.”

Professor Kidd studied history at Cambridge and Harvard, USA, before doing his doctorate at Oxford.

He was a lecturer and professor at Glasgow University then, after a short period at Queens University Belfast, he came to St Andrews University in 2012.

Specialising in intellectual history including religion, literature, history of science and history of ideas, he has worked with Gerard Carruthers, who is the Frances Hutchison professor of Scottish literature at Glasgow University, in the past.

However, while there has been some previous academic work on the relationship between literature and nationhood, this is the first time there has been a meaningful look at the relationship between literature and unions.

Professor Kidd says: “One of the things that struck me going into the independence referendum of 2014 was that 90% plus, getting on for 100% of all those involved in the writing scene in Scotland – poets and playwrights, novelists and so on – were behind independence.

“That’s somewhat unusual because writers are quite a contrary bunch up for argument and disagreement and so on.

“But they seemed to be of one voice on this.

“It struck me that most of the main works that we think of as the canon of Scottish literature were all composed within the Union of the Crowns or mostly after 1707 – between 1707 and the present.

“In other words, Scottish literature, at first sight doesn’t seem to have suffered from the Union.

“A flourishing Scottish literature has been compatible with shared political arrangements with England.

“I guess the second question was that if the Union has been a bad thing for Scottish culture then what we might expect is that the Union of 1707 would be a major element in Scottish writing.

“The Scottish writers would have investigated and debated and criticised the Union.

“There’s a very famous poem by Robert Burns; there’s a few references here and there by other works. But by and large the Union has been largely invisible in Scottish culture.”

Professor Kidd goes on to say that the “big things” in Scottish culture through the 18th, 19th and into the 20th century have actually been Jacobitism and the legacy of the Covenanters – the persecuted Presbyterians of the late 17th century and Calvinism.

He adds: “In other words until the very recent past we don’t actually see much reference to the Union – it’s more if you like two different party views of Scottish politics and history and religion.

“On the one hand it’s the views of Royalists and Episcopalians on the Jacobite side, and on the other a kind of Presbyterian Calvinist view of Scottish history. That’s been the main division.

“I suppose partly where I come from is that religion for most of the history of the Union was what created tensions not just within Scotland but also between Scotland and England leading to things like the Disruption of 1843 when the Free Church broke away from the Church of Scotland.

That was the main dividing line.

“In other words I think that secularisation and a drift away from the churches has, as it were, created some kind of vacuum in Scottish life where people now find meaning, find identity, in a national allegiance.”

Historians can often make predictions about the future after learning from the past.

But Professor Kidd admits that such is the pace of political change in Britain at the moment, it’s “almost impossible” to predict what will happen next.

“Things seem to change so much at the moment from year to year,” he says.

“We are in a period of turbulence in which the electorate seems to be very volatile.

“It’s sometimes very easy to forget what the very recent past was like.”

The unexpected Brexit result in 2016 means there are now four permutations on Scotland’s future – double Unionists who are pro EU, pro-UK; double independents who want Scottish independence outside the EU; those who are pro-independence and pro-EU and those who want a UK out of the EU.

Professor Kidd says this has actually been “healthy” for Scottish society because “it was getting a bit unhealthy that we had two groups who were so polarised over Yes/No.”

He adds: “It’s now complicated things. But I think it’s probably better for good manners and civility and the health of debate when things are a bit more complicated than they were before.

“But who would have guessed in 2014 what we saw in 2016 just as who would have guessed in 2012 what 2014 would be like.

“Things are changing so rapidly. Historians are used to thinking in terms of centuries or decades but actually things are now changing so dramatically that it seems the speed at which people are changing their minds about things – it’s become so rapid it’s hard to predict what’s coming next.”

*Literature and Union: Scottish texts, British Contexts, published by Oxford University Press,is on sale now priced £30.