Could “lost treasure” – including the relics of Scotland’s patron saint – lie hidden beneath the ruins of St Andrews Cathedral – or is the suggestion a misguided dream? Michael Alexander speaks to an author and researcher who hopes to solve a 500-year-old mystery.

In the middle of the Jannettas Gelateria café in St Andrews’ South Street on a Wednesday afternoon, Rick Falconer is enthusiastically contrasting the modern day “magnetism” of St Andrews tourism with the medieval allure of the cathedral which attracted 20 million pilgrims from across Europe between the 14th and 16th centuries.

The author and ghost tour guide, who describes himself as an “open-minded sceptic” when it comes to the paranormal, is talking about the “sheer impact of emotion” of those who travelled hundreds or thousands of miles to “atone for their sins” – and speculating how this energy could have left its mark on the very fabric of the town when cathedral stone was quarried for many town centre buildings after the Reformation.

“Everything is energy and it impacts on the locality,” he says.

“If you imagine the sheer impact of emotion of millions of people coming here: family and friends dying of the Black Death or cholera en route then realising they might not make the return journey.

“Even then they would only get into the cathedral if they were free of disease – and had money.

“That intensity of emotion – if you convert it to energy, it’s possible it’s gone bang into the fabric of the stone and that’s infused through the centre of St Andrews leading to the countless ghost sightings we still hear about to this day.”

Whether you believe that religion – or indeed the paranormal – is fact, fiction or fantasy, there’s no disputing that in the Middle Ages, St Andrews Cathedral was one of the greatest seats of Catholic power in Europe outside of Rome.

Taking 158 years to build before being dedicated on July 5 1318 in a ceremony before King Robert I, St Andrews Cathedral became the centre of the medieval Catholic Church in Scotland and remains the largest church to have been built north of the border.

The two main pilgrimage routes in Europe outside of Rome were St Andrews and Santiago de Compostela in Spain, and with Saint Andrew being the patron saint of Scotland as well as other countries including Greece, Romania and Russia, the directive back then from the Catholic church was that pilgrims came to be blessed by the healing powers of the saints as an atonement for their sins.

“At the time St Andrews Cathedral held the largest collection of medieval art in Scotland and was full of white marble, 30 altars, a large statue of Christ up at the high altar, and there was a chest that weighed 1.5 tonnes containing the relics of Saint Andrew,” says Rick.

“It was a massive money making venture on the part of the Catholic Church,” he adds.

But in 1559, during the Scottish Reformation, everything changed.

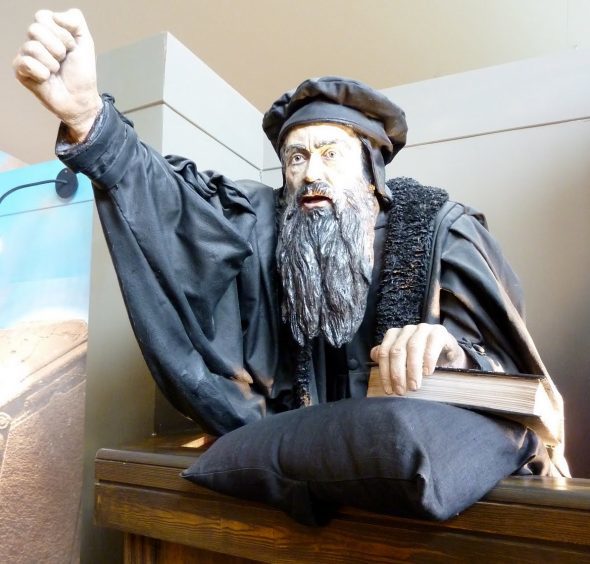

As waves of disgruntlement against the Catholic Church grew across Europe following decades of martyrdom by opponents, John Knox preached his now famous “fiery sermon” in St Andrews parish church, and the cathedral was “cleansed” as a result.

History records that it was robbed of its prized possessions after being stormed by a local mob and by 1561 it had been abandoned and left to fall into ruin – the start of a period which then saw St Andrews itself go into three centuries of decline as the pilgrims, and indeed the merchants, stopped coming.

At about the end of the 16th century the cathedral’s central tower apparently gave way, carrying with it the north wall.

Afterwards large portions of the ruins were taken away for building purposes, and nothing was done to preserve them until 1826, leading eventually to the well maintained ruins that we see in the care of Historic Scotland today.

But with no specific records of the sacred possessions of St Andrews Cathedral being destroyed, is it possible that the monks had time to hide them away in yet to be discovered catacombs beneath the cathedral?

It was a possibility that captured the imagination of Northumberland-born former St Andrews town councillor and author W.T. Linskill in the late 19th/early 20th centuries.

Excited by the accidental discovery of the mine and countermine at the castle in 1879, he established the St Andrews Antiquarian Society – a body of historians, academics and professors – with the aim of finding the “lost treasure” of St Andrews.

Linskill believed the tunnel continued all the way to the cathedral and started raising funds for digs.

In the 1890s he searched for the ‘Wee Stair’ near the High Altar of the cathedral which had apparently been filled in by 18 workmen following an accidental discovery during rubble clearance in 1842.

He speculated that this reportedly tight stone staircase leading straight into the ground around a grand marble columns could be a passageway leading to forgotten vaults where the treasure could lie.

However, it could not be found as the ruins had changed so much following rubble clearance and after 50 years of making national headlines, enthusiasm for the project died with Linskill’s passing in 1929.

Now, almost a century on, Falconer is in the early stages of seeking permission to resurrect Linskill’s work and has ambitions for a professional ground penetrating radar survey to be carried out at the cathedral to find out if hidden underground chambers – potentially containing “treasure” – might indeed exist.

The author recently carried out meticulous research into St Andrews’ most famous ghost the ‘White Lady’ for a recent book.

The story was given some credence in the 19th century when 10 coffins – including the body of a mummified young lady in a white dress – were accidentally discovered in a ‘Chamber of Corpses’ built into a tower in the cathedral’s northern wall.

Falconer believes these relics were the remains of “local saints”, possibly dating back to Pictish times, who had been worshipped in the medieval cathedral.

He believes they were bricked up by the monks for safe keeping as the Reformation loomed – and he sees no reason why other priceless artefacts from the cathedral’s heyday should not remain hidden beneath ground.

“If you look under the majority of cathedrals around the world, there’s tunnels, there’s caves, there’s all sort of places where they did hide valuables in times of trouble,” says Rick, who is employing a researcher later this year to delve into Vatican records dating back to the 12th century.

“Linskill believed that St Andrews was no different. He said that if St Andrews Cathedral did not have the passages it would be like a bank not having a bank vault.

“He believed they hid the treasure underground and that they would not have taken them to sea because these things were priceless. They couldn’t afford to be lost in storm.”

Conscious of the potential sensitivities of surveying a graveyard, Rick hopes to get St Andrews University and Historic Scotland on board as he moves forward with his research.

“To finally solve this would be the most incredible thing for Scotland,” he says.

“Saint Andrew being the patron saint, the lost treasure of Scotland in St Andrews, would be an amazing thing – an amazing legacy for Linskill and for the town. It would be overwhelming. One of the greatest finds ever!”

But others are not so sure.

Historian Dr Bess Rhodes is part of the inter-disciplinary Open Virtual Worlds / Smart History team at St Andrews University which specialises in applying new technologies to study of the past (e.g. through digital reconstructions of historic sites).

She is currently undertaking research into the cathedral’s history, and is part of a team that is working on digitally reconstructing pre-Reformation St Andrews.

But while she applauds Mr Falconer’s research and looks forward to hearing if he makes any breakthroughs, it is her opinion that suggestions of treasure beneath the cathedral are “probably rather far-fetched”.

She says: “We know the cathedral had relatively sophisticated drainage systems. We know this from the latrine and the wells that can still be seen. We also know there was a Mill Lade. I believe there are elements of this yet to be discovered.

“But one of the things that makes me dubious about there being a crypt is what we know about the foundations just built on earth and rock, and there being no written evidence of underground chambers.

“What is possible in relation to the mine and countermine at the castle is that there are other undiscovered attempts to dig into the castle during the siege.

“The stories probably perpetuated after the Reformation when people accidentally found bits of the drainage system.

“Treasure can’t be ruled out. But we have evidence of stuff being burned and what is most likely is that silver and gold artefacts would have been melted down as is what happened at St Giles in Edinburgh and Aberdeen.

“We also have to consider that at the time of the Reformation, a lot of the people running the cathedral were sympathetic to Protestant reform.”

Fife Council archaeologist Douglas Speirs also welcomes efforts by Mr Falconer to promote “an alternative approach to the exploration of St Andrews’ past”.

Describing Linskill as a “Boris Johnson-like character” in early 20th century St Andrews, he says he actually made some “very significant archaeological discoveries” in his ‘howkings’ around the town.

However, he describes Linskill’s suggestion of an underground passage connecting the cathedral and castle as “quite ridiculous” – and points out that most of his ghost stories were “works of complete fiction”.

Linskill’s ‘Strange Story of St. Andrews Haunted Tower’ published in 1925 was “loosely based on real events”, Mr Speirs says.

But he says it was “sensationalised and exaggerated” and that there is “no mystery”.

Mr Speirs said what was discovered was clearly a mausoleum of early 18th century date. Natural dessication resulting from environmental conditions within the mausoleum, rather than mummification, explains the degree of preservation, he claims.

“If Mr Falconer is in contact with the spirits then it is entirely possible that he has access to sources of information unknown to me,” adds Mr Speirs.

“But the historical and archaeological evidence does not bode well for his enterprise.

“Linskill’s quest was doomed before it ever started, and I believe the same is true of the present plan.

“Why? Because Linskill’s belief in the existence of a buried passage full of treasure was a product of his imagination and not a conclusion borne of historical research.

“Consequently, his many years of ‘howkings’ were in fact little more than the recreational pursuit of a wealthy, connected and over-indulged dreamer allowed to practice his fantasist historical passions in an age before fragile archaeological remains were properly protected.

“Linskill wilfully deluded himself and I think anyone wishing to follow in his footsteps would be doing the same.

“ There is no historical basis for a belief in a subterranean passage at St Andrews and the thought that it should be filled with episcopal treasures hidden at the Reformation displays a limited understanding of the lengthy process of social, political and religious change encapsulated in the term ‘Reformation’.

“It is true that St Andrews, like Perth, did experience violent popular uprisings in 1559 but the key competing interests in the wealth of the Church – the Crown, secular interests and the Reformed Church – are unlikely to have allowed the movable wealth of the cathedral and priory simply to have vanished.

“Even if it had been hidden, would the treasures not have been retrieved at some later date?

“After all, Archibishop John Hamilton of St Andrews continued on in post after the Reformation, and despite a short period of imprisonment in 1563, managed to stay in post until his execution in 1571.”

Mr Speirs says there’s no doubt the Reformation undoubtedly robbed Scotland of a “truly phenomenal wealth of medieval religious plate, art, vestments, books, relics and architecture.”

“One need only visit the great episcopal museums of the Continent, particularly Italy, to see exactly what St Andrews Cathedral lost as a result of the Reformation,” he says.

“But for the most part, this loss was not a product of chaotic rioting.

“Rioting did happen; buildings were ransacked and religious wealth, relics and art were both pinched by rioters and smuggled out to the Continent by fleeing clerics, but for the most part the transfer of the Church’s considerable wealth was a slow, organised and lengthy process.

“Consequently, the thought of the movable wealth of the cathedral and priory being hidden and never thereafter recovered, seems profoundly unlikely.”

In short, Mr Speirs thinks it is “deeply unlikely” that movable wealth of the priory cathedral remains to be discovered buried at St Andrews.

Moreover, having considerable experience of the use and limitations of ground penetrating radar (GPR), he thinks it even less likely that a GPR survey would find such a chamber, even if it existed.

“The ground around the cathedral has been used as a burying ground for hundreds of years and is so disturbed that any readings returned would be meaningless,” he adds.

“Scheduled monument consent would also be required for such a survey and whilst it’s theoretically possible that consent could be obtained, any anomaly detected would have to be excavated to be explained, and the chances of securing scheduled monument consent to excavate an anomaly at the cathedral on the grounds that it might contain treasure are zero.

“But having said all this, I genuinely wish Mr Falconer well in his work in promoting an alternative approach to the exploration of St Andrews past.

“Historians and archaeologists all too often fail to bring the past to life, so if it can be done in other ways, for example through ghost tours, then all to the good.

“The key thing is that Mr Falconer is working to promote the public’s wider enjoyment, exploration and appreciation of the shared cultural inheritance that is our past and that can only be a good thing for St Andrews, arguably Scotland’s most historically significant burgh.”