Michael Alexander visited Dunfermline to find out how the scanning of a 925-year-old relic of St Margaret (Queen of Scotland) could reveal secrets from the past.

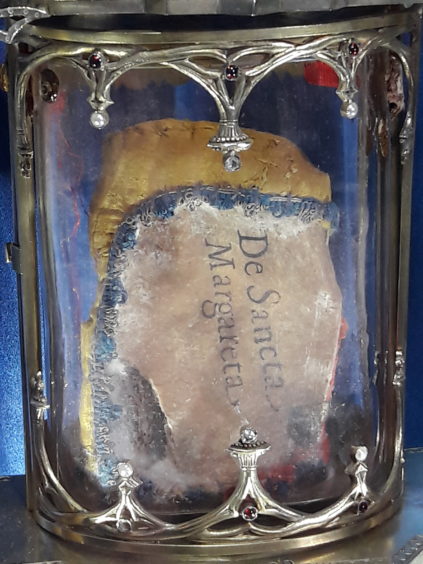

Teasing open the back door of the altar table and carefully removing the crystal reliquary in which the 920-year-old shoulder bone fragment of St Margaret (Queen of Scotland) has been housed since 1886, Father Chris Heenan, parish priest at St Margaret’s RC Memorial Church in Dunfermline, respectfully removed the divine relic from its display case.

Placing it on a table in front of him, Father Heenan said a prayer in memory of St Margaret’s “outstanding charity towards the poor” and called on all humanity to reflect on her example before handing the relic to archaeologists who set about using the latest technology to 3D scan the bone in a bid to find out more about one of the most venerated figures in Scottish history.

St Margaret (Queen of Scotland) is perhaps best known for the work she did to help the poor during the 11th century.

She also introduced things like knives and forks to Scotland and North and South Queensferry are named after her because she set up a ferry for pilgrims going to St Andrews.

The naming of the Queensferry Crossing is the most recent tribute to her memory.

However, experts now hope that by using 3D scanning technology, they can discover more about her lifestyle, as well as producing an exact replica which people can hold without fear of breaking an ancient artefact.

Glasgow University archaeology student Lauren Gill, from Cardiff, and Martin Lane from Cardiff Metropolitan University visited St Margaret’s RC Memorial Church to do the study on Tuesday, and Lauren, who is doing the project for her final year dissertation, confirmed that special permission had been granted by Archbishop Leo Cushley before work could begin.

“What I really want to do is look at how useful 3D scans of first class relics like this are,” she told The Courier.

“First class relics used to be so important to the church, to politics, they were traded between monarchs and heads of state – they were vastly important to everyday life almost in medieval Europe and I think it’s really sad they have lost that position.

“I think they are fantastic and I think they are normally so well preserved and revered that they can tell us so much about the people that they come from.”

Lauren said she was not planning invasive testing. However, if this was carried out it might be possible to spot signs of disease, malnutrition and lifestyle.

“I’m not an osteo-archaeologist or a bio-archaeologist,” she added, “but I’m going to have a quick look. You can tell already she was very small, and that is normal for a woman of her era.

“I can’t see any sign of disease but the scapula is not really the right bone to see signs. “You can’t really predict her height but she was very very small and we know she fasted a lot in life, and if she started that early enough before puberty it would make sense to be that small.

“What I want to focus on is the relic after her death more than her life. A focus on how people venerated bones like this.”

When Queen Margaret died in Edinburgh Castle in 1093 – days after the death of her husband Malcolm III – her body was taken back to Dunfermline via the ferry and buried.

After being made a saint by Pope Innocent IV in 1249, a shrine was built at Dunfermline where she laid intact until the 16th century when Mary, Queen of Scots asked for her head to be sent to her, to bring her help as she gave birth to her son who would become King James VI.

Her head was then taken to a Jesuit College in Douai, France, but was never seen again after the French Revolution.

As the Reformation gathered pace and threatened to destroy Catholic churches, the remainder of her body was secreted away in the 16th century, ultimately being taken to Escorial Monastery by Philip II of Spain.

It wasn’t until the 19th century that Bishop James Gillis of Edinburgh sought permission from Pope Pious IX for a relic to be brought to Scotland.

They sawed a piece of the shoulder bone off and they sealed it with the seal of the Escorial.

Bishop Gillis brought it back to Scotland to be placed in St Margaret’s Convent in Edinburgh but when the convent closed it was moved to St Margaret’s RC Memorial Church in Dunfermline in 2008 where it has been since.

Jack Pryde, 72, an expert in Dunfermline history who has been running Discover Dunfermline walking tours since 2011, said St Margaret – who was born in Hungary where her English family was in exile – is not appreciated in Scotland as much as she should be.

The former electrician, engineer and Dunfermline Building Society employee told The Courier: “From 1985 I was one of the founding Dunfermline Heritage guides – a scheme to mark the 150th anniversary of Andrew Carnegie.

“But so many people don’t know about St Margaret. What I keep saying is if we got the coverage they get in France for St Bernadette and all these places, this is a huge market. I hate to secularise it in that manner but that is the way it is.

“She was a huge person. She’s not recognised for all the good that she did in her time, living with her husband King Malcolm III. She had a tremendous impact – not just on Dunfermline – but on Scotland in general.

“I hope this study will help bring a refocus on Margaret to rediscover who she was and what she is. She did some amazing things for the poor, brought in forks and knives to Scotland – she Europeanised us!”

During the six years that Father Christopher Heenan has been the parish priest at St Margaret’s in Dunfermline, it has often crossed his mind that when he celebrates mass on the altar in the small chapel which houses the relic, those same words were the final ones to be spoken by Queen Margaret on her deathbed more than 925 years ago.

“We know that her last recorded words were a prayer from the mass so when I say that prayer celebrating mass I’m always thinking they were the last words of St Margaret – bringing that link down through the centuries,” he said.

However, Father Heenan, who has been a priest for almost 24 years, felt even closer to St Margaret when he was given the privilege of opening the reliquary for the first time since Archbishop McDonald did so in 1938.

“I received the present archbishop’s permission to open it for this scanning and study, so last week we actually unsealed it and opened it to check everything was ok ahead of today,” revealed Father Heenan, who was previously a priest in West Calder, Cardenden, Kilsyth, Falkirk, and also has experience as a prison chaplain.

“We were pleased to discover that after 925 years the bone still seems to be in good condition.

“That was the first time I touched it which was actually quite amazing.

“We can still go and visit the places where she went. But to actually touch the relic – a word which comes from the Latin ‘what’s left behind’ – it just brings that certain closeness to a woman who was inspirational in so many ways.”

Father Heenan said other bones belonging to St Margaret are still housed in the Escorial.

However, the “wonderful thing” about having a 3D print will be that people can now touch an exact replica.

He added: “We get quite a few school groups who come.

“They love the story of Margaret. It’s a fantastic story – you’ve got Macbeth, Malcolm, there’s Harold, there’s William the Conqueror, the Norman Conquests. There are ships. People exiled. There’s amazing elements to the story.

“I think for people to hold something that’s tangible will be quite special to see their reaction.

“The whole thing about relics is that we don’t worship relics. In a way it’s about the attraction of holiness and being in touch with somebody who’s lived an exemplary life – someone who was real and who lived in Dunfermline. I think that’s very important for Dunfermline as a whole.

“We look forward to our annual pilgrimage on June 2 when we invite people from all over Scotland to learn more about St Margaret and the history of Dunfermline.”

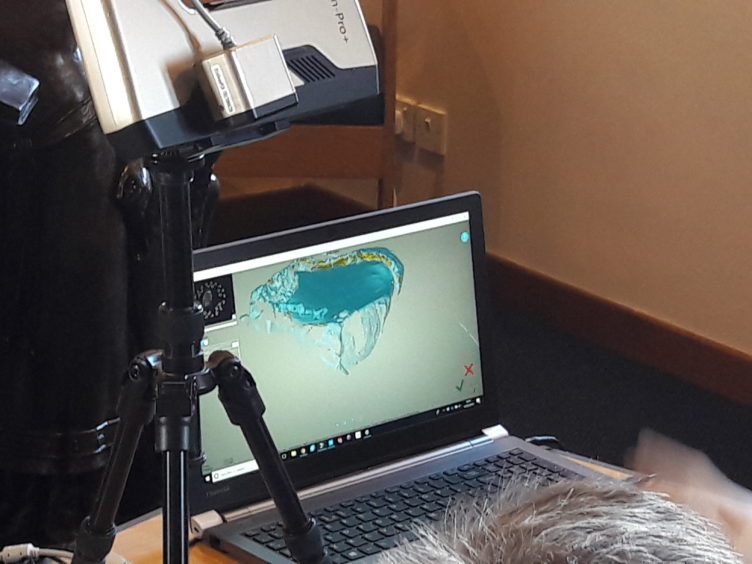

Meanwhile, the technology used to 3D scan the St Margaret relic in Dunfermline was the same equipment used to scan and recreate leg bones of the purser found amongst the wreck of King Henry VIII’s carrack-type warship the Mary Rose.

This was revealed by Martin Lane, co-ordinator of the Fabrication Lab in Cardiff Metropolitan University, who travelled to Dunfermline with Lauren Gill to carry out the work.

His department specialises in 3D scanners, laser cutters and other tech which helps students and has also been used for prototype projects involving the British Army and NHS.

Explaining how he got involved through Lauren’s father who used to sit on the same community projects board at his university, he knew nothing about Queen Margaret beforehand but was delighted to get on board and learn more.

“In this instance the camera sits on a tripod from two different angles,” he explained. “The light is patterned and the camera reads the way the light refracts over the surface and distortes it .

“I’ll provide Lauren with a scan then we’ll 3D print one. It’s a clever process.”