The hidden histories of prisoner-patients locked up in Perth during the Victorian era is explored in a new free exhibition by National Records Scotland (NRS) which opens on Thursday August 1.

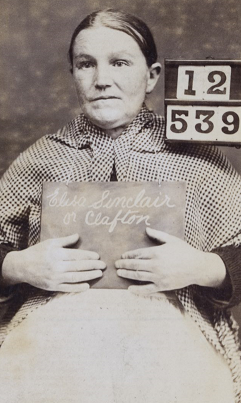

Prisoners or Patients? Criminal Insanity in Victorian Scotland uses never before displayed records and photographs to reveal tragic stories of crime, treatment, recovery and release.

Guest curator Professor Rab Houston of St Andrews University has selected an array of images and objects from the trials of people accused of murder and other serious crimes at the High Court of Justiciary and the Criminal Lunatic Department in Perth – including photographs, personal notes and petitions of prisoner-patients, a prison register, crime scene map, court papers and medical reports.

The exhibition, which runs at General Register House in Edinburgh for the duration of the Fringe, provides an insight into historic penal policies and the infancy of psychiatry, revealing the stories of people – occasionally dangerous, often vulnerable but always severely disturbed – who experienced mental health problems and impairments in the moist extreme circumstances.

In an interview with The Courier at the launch in Edinburgh on Wednesday, Professor Houston explained how the Criminal Lunatic Department at Perth Prison was the “Carstairs of its day” and explores how those labelled as criminal lunatics and afflicted by mental health issues at the time were treated.

He was inspired to pull the exhibition together after running a ‘Face to Face’ exhibition about Liff at Dundee University Tower Extension a few years ago – and taking it on a tour of prisons.

“The records are amazing because most of the people are from backgrounds of the type that just don’t appear in history,” he said. “It’s fascinating. Harrowing at times, humane at others. It’s completely wonderful.”

Perth Prison dates from the 1810s when it was built by Napoleonic /French prisoners.

The Criminal Lunatic Department, which served the whole of Scotland, opened in 1846 with a mirror building for women lunatics opening in 1881. This doubled the capacity from around 50 to 100.

He explained that a criminal lunatic was somebody who was accused or convicted of a serious criminal offence and detained indefinitely at Her Majesty’s pleasure until deemed as “no longer a threat to themselves or society”.

But while padded cells and restraints were used when required, Professor Houston said he was surprised when researching how much help was given to prisoners before the facility closed in 1957.

“The big difference now is we have a full range of drugs to manage mental health symptoms,” he said when contrasting today’s approach to psychotic prisoners.

“In the 19th century up until the 1950s/60s, there were very few treatments. But it shows that efforts were made for criminal lunatics to be helped.

“That’s one thing that struck me about the whole thing. These people weren’t hanged. They did their best to look after them and did their best to get them out.”

Professor Houston said the case studies he found “most affecting” were the women – many of whom killed their own children. “It’s those that stand out for me,” he added.

But another case that strikes a chord with him is the story of Alexander McKinnon – the youngest person in the exhibition – who was just 18 when he was admitted to Perth.

He received a seven-year sentence in May 1880 after being caught red-handed in a shop in Glasgow wearing eight stolen items of clothing. He was looking at himself in the mirror when the police arrived.

“He’s not violent,” added Professor Houston, “but he’s very disturbed and very sad. Looking at these peoples faces and they really speak to you.”

One of the most violent cases highlighted in the exhibition is that of Angus McPhee – a manic depressive and “serial masturbator” who was “absolutely crazy” and bludgeoned his aunt and parents to death

Born on Christmas night 1832, Angus was 26 years old when he was admitted to Perth CLD after committing the murders ‘in a maniacal paroxysm’ in an isolated community on the island of Benbecula leaving their bodies ‘mangled and bloody’.

During his first three months at the CLD, Angus was more or less continuously deranged, experiencing sudden episodes of violent insanity.

Liable to “periods of exaltation and destructiveness with recurrent attacks of mania” when “furiously maniacal”, Angus was put in a straight-jacket and anklets and in handcuffs when less so.

In more placid periods he suffered from persistently held delusions.

The prison surgeon noted that he was fixated by his genitals. Reported in 1877 to be in love with one of the female attendants, Angus was a “chronic masturbator” who was given Potassium Bromide, a sedative and anti-convulsant, which also calmed sexual excitement.

Another murderer featured is Elizabeth Gilchrist or Brown who was admitted in 1868.

She was 21 when she killed her six month old daughter Jessie by giving her laudanum because “the child had been troublesome and was teething and I thought the laudanum would make her sleep”. Yet moments later she admitted “I did mean to destroy her”.

Then there’s John McFadyen, admitted in 1872, for the drowning of two-year-old Alexander Shields in the River Clyde at Glasgow. He abducted ‘Sandy’ from the street while the boy was waiting to greet his father’s return from work, stripped him and threw him in the water, holding him down with a stick. The child’s distraught mother caught him running away with her son’s clothes.

Monikie-raised Jocelyn Grant – senior outreach manager with the National Records of Scotland who helped curate the exhibition – said she had also been struck by how “compassionate” the authorities were to ‘lunatics’ in the days of the Criminal Lunatic Department at Perth.

“What’s interesting is the process that’s been gone through to determine whether these people were lunatics or not and how best to treat them,” she said, adding that the records gave a real snapshot of social history.

The NRS archives touch on every aspect of Scottish life. In particular, they have a lot of records relating to criminal prosecutions and court proceedings which means they can get a very detailed look at lives that might not otherwise have been recorded.

“It’s an odd situation,” said Jocelyn, “that if you have an ancestor who was a criminal, we probably have more information about them than if they were a law abiding citizen!”

Paul Lowe, chief executive of NRS, said: “Professor Houston and NRS archivists have brought together a collection of fascinating items that tell a compelling story about people furthest from public sympathy with great dignity and humanity. It shows how historical and cultural trwasures within the archives of National Records of Scotland can bring the past to life.”

*Prisoners or Patients? Criminal Insanity in Victorian Scotland runs until August 30 at the Matheson Dome, General Register House, 2 Princes Street, Edinburgh. Admission is free and opening times are 10 am to 4.30pm.