Could the Youth in Iceland Model approach to preventing young people from using drugs and alcohol help tackle Dundee’s drug crisis?

That’s the question posed by researchers at Stirling University who have been studying whether the Icelandic system could be introduced in the city.

The model was developed in the Nordic nation over 20 years ago and since its implementation has seen a significant reduction in substance use among teens.

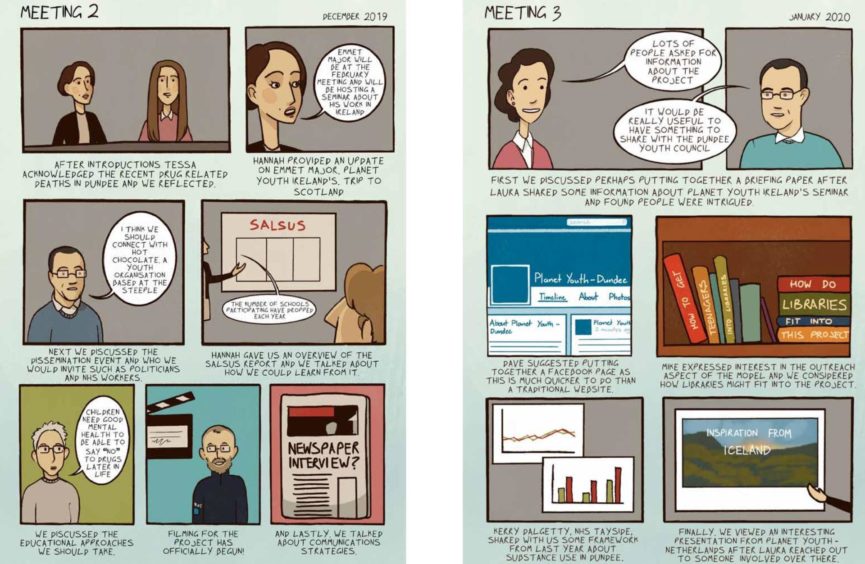

The Stirling University project, led by Dr Tessa Parkes and Dr Hannah Carver and funded by the Society for the Study of Addiction, has brought together a diverse group of individuals to gain an understanding of how the model could be adapted locally.

We spoke to those involved to find out if Dundee could become the first city in the UK to adopt the Youth in Iceland model.

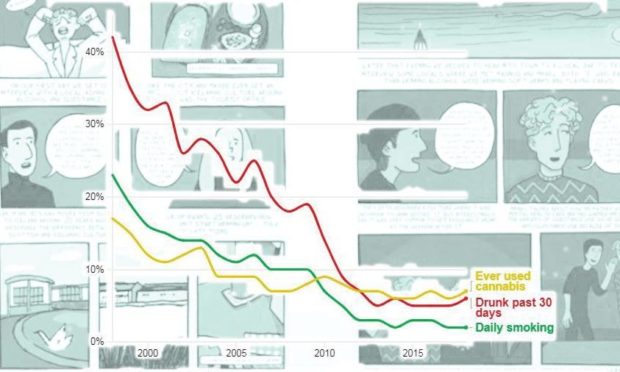

In the mid-1990s, Iceland had one of the worst rates of teen substance abuse in Europe.

A series of national surveys in schools reported that more than 40% of those between the age of 13 and 16 had been drunk in the past month.

It also showed that 25% had reported smoking every day and a further 17% admitted using marijuana.

Crucially, however, the surveys showed researchers the differences in the lives of those who engaged in substance use and those who did not.

What the data highlighted was a clear emergence of protective factors: participation in extracurricular activities, time spent with parents, and how they felt about schooling.

In short, the more engaged young people were with sport and other activities, and the more time they spent with their families, the less likely they were to use substances.

With this in mind, a new approach to prevention was rolled out across the country.

What is the Icelandic model?

Dubbed the Youth in Iceland Model (YiIM), the community-based approach aimed to delay young people’s substance use through reducing risk factors and increasing protective ones.

It strengthened links between schools and communities, as well as encouraging parents to spend quality time with their children.

State funding was also increased for organised sport, music, art, dance and other clubs.

The results speak for themselves.

Figures show that in 2015, the rate of smoking tobacco was 46% among 15-year-olds in Europe but had dropped to 16% in Iceland; average rates of current alcohol use were 48% in Europe but 9% in Iceland; and average rates of lifetime use of cannabis substances remained at 16% in Europe, similar to 1999, but declined to 5% in Iceland.

Following its success in Iceland, the model has since been introduced in more than 30 countries around the world (under the name Planet Youth), with adaptions to suit locally specific conditions.

Now Scotland could be next – with Dundee leading the way.

A key component of the model is information about young people’s health and wellbeing, including substance use, which is gathered through surveys distributed in schools.

Protective factors are then developed by the community in response to the data, and schools are encouraged to strengthen supportive networks between themselves, parents, and other community organisations.

Plans are underway to trial the survey in at least one secondary school in Dundee before potentially rolling it out to other areas of the city.

Audrey May, chief education officer at Dundee City Council, is closely involved with the project and explained how this model of prevention has the voices of young people front and centre.

“Think of it like a customer satisfaction survey,” she said.

“It’s about the choices they make around leisure time, how much they are involved in activities, how much screen time they have, sleep patterns, etc.”

“And of course, have they begun to experiment with tobacco, alcohol and other substances?

“We get an idea of what they are doing and where we can support them to make different choices that will help them to lead happy, healthy lives.”

Creating a support network

Working closely with Audrey on the project is Sarah Anderson, education support officer for health and wellbeing at Dundee City Council.

For Sarah, the YiIM is less about reiterating the dangers of drugs and alcohol to young people but rather giving them the tools to make better decisions by finding out what services the city is lacking.

She said: “We need to be really honest about what we are doing around drug use and its prevention.

“I’m sure if you talk to young people, they will be able to tell you the dangers of smoking or drinking alcohol.

“So this model is about building on that existing knowledge and developing their skills so they are supported in their decision making and they have a wider support network.”

What could be missing from Dundee’s version of the YiIM model?

One element of the YiIM is that 50,000 króna (around £300) is given to every family for extracurricular activities in the form of a leisure card.

The grant is an important aspect of the model, allowing kids to access activities in their area without fear of cost.

However, there is currently no funding for this in Dundee.

The city has no comprehensive directory of sport and other activities, and available services are described as “disjointed”.

One thing that does currently exist is the infrastructure needed to implement the project, and key to the success of the YiIM in Dundee, is finding a way to utilise this.

Audrey said: “If you look at what’s available in Dundee in terms of opportunities for young people, there’s so much for them to be engaged with.

“Let’s be honest though, the barrier is around the cost.

“It’s not about suddenly making everything free, but rather how we charge for some of these opportunities and how we change that. Is there a different way to fund that to make it more accessible?”

Getting young people to abstain from drugs and alcohol is a challenge faced by every generation, but previous campaigns have perhaps fallen short of the mark.

Is it not worth trying for this generation of young people so that they don’t become the next set of statistics going forward?”

Audrey May, Dundee City Council

“We can’t keep doing what we have always done and maybe we have to admit that it’s not worked as well we would’ve wanted it to,” Audrey said.

“Here’s a different approach. Is it not worth trying for this generation of young people so that they don’t become the next set of statistics going forward?”

What does the research say?

What the statistics show is that early use of drugs dramatically increases the risk of lifelong substance use disorder.

One study revealed teens who initiate drug use before the age of 14 are at greatest risk for substance dependence and have a 34% prevalence rate of lifetime substance use.

Someone who has faced the torment of a loved one’s drug addiction is Dundee grandmother, Pat Tyrie.

“It’s a devastating experience,” she says.

“You lose your child to substance use and you can spend 20-odd years of angst trying to help them.

“My child is a lovely person, but you have lost that person. They haven’t had a life really and there’s huge disappointment around where that might’ve gone.

“The distress that it causes, in the moment and the long term, is almost unbearable if you were to think about it.”

You lose your child to substance use and you can spend 20-odd years of angst trying to help them.”

Grandmother Pat Tyrie, of Dundee Drugs Commission

It’s her personal experience that led to Pat becoming a member of Dundee Drugs Commission, an independent group tasked with considering what more can be done to turn around the rate of drug deaths in Dundee.

Through the commission, she has also become involved in the discussions around how the YiIM could work in the city; something she dubs an ‘application of common sense’.

She said: “During one of our meetings I became aware of this model that was happening in Iceland. I read an article about it and thought, why are we not doing this?

“It seemed pretty straight forward. They’ve used this model, developed it over 20 years and had a massive reduction in the number of young people who are engaging in substance use.”

In essence, the YiIM is a collective attempt to help solve a problem whose ripple effect is felt by services across the whole community.

Figures from NHS Tayside show that between 2012 and 2017, there were more than 7,500 admissions to emergency departments in the region for drug overdoses.

The majority of these were aged between 21 and 30.

There are problems, too, with drug paraphernalia being inappropriately disposed of in Dundee and more than 600 needles were found in the city in 2019 alone.

This has led to the local council having to form a drugs related litter group to deal with the issue.

My child is a lovely person, but you have lost that person.”

Pat Tyrie

So if public services are already bearing the brunt of the adverse effects of substance misuse, can they also be at the forefront of its solution?

Pat said: “On an individual level, you don’t want your child to use drugs. On a community level, you don’t want children using drugs – nobody wants it.

“So I think it’s healthy for a city to be involved with the provision of extra-circular activities for its young people.

“Make community centres available to young people, make transport available to young people.

“We need parental involvement, but they need to be supported by the wider structure of our society which is our local and national government.”

Dundee ‘drug death capital of Europe’

Dundee is currently in the grips of a drugs crisis.

Figures published last year show that deaths in the city from drug-related causes rose from 66 in 2018 to 72 in 2019.

The city also has the worst drug death rate in Scotland at an average of 0.36 per 1,000 of the population over the past five years.

There are alarming figures, too, about substance use among teenagers.

One report, which went before a council committee last December, showed more than 40% of young people aged between 11 and 15 in the city have reported using substances in the previous 12 months.

Two people who have been on the front-line of this crisis are Dave Barrie, service manager at addiction support charity We Are With You, and Simon Little, chair of the Dundee Alcohol and Drug Partnership (DADP).

“For me, one of the strengths is that at the heart of the model is the young people,” Dave said.

“You are having a collective group of people, including parents and schools, around the table to really start to understand what the young people are saying right now about their health and wellbeing and substance misuse.

“They tell us what is going on and then groups of adults with them start to understand and analyse that to see where the focus needs to be.”

Much of the focus of Dundee’s drug problem has been on the increasing number of fatal overdoses in the city and how best to reverse this trend.

But as Simon explains, even if authorities are successful in tackling this in the short term, the impact of these deaths will continue to be felt for years to come.

He said: “The drug deaths are one indicator of the challenges we have in the city and the fact they have been going in the wrong direction has to be an alarm bell for all of us.

“Putting out that particular fire is vital, but we will also have difficulties down the line unless we are mindful of the trauma those deaths are creating for the city as a whole.

“We know that when children have adverse childhood experiences they are more likely to have difficulties in the future, so with the challenges the city currently has, the time to act is now.”

Tackling the root causes

Indeed, research in the US shows that of adolescents receiving treatment for substance abuse, more than 70% had a history of trauma exposure.

It’s also been found that up to 59% of young people with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) subsequently develop substance abuse problems.

That’s why the DADP has made tackling the root causes of substance misuse one of its 12 strategic priorities, and why models of prevention such as the YiIM can be crucial to helping prevent future generations from falling into the cycle of drug abuse.

Simon said: “In the short term, it’s actually quite difficult for people to make the leap of faith and say what we are doing now will be so important to change things in 10 or 20 years’ time.

“There is often a bias towards firefighting versus long term strategies, but we could potentially reap the damage with the next generation with the problems we have now.

“So, I’m keen to see [the YiIM] not just as a silo for tacking drug problems but something to support future generations.

“If rolled out across the city I think it will have positive impacts that go well beyond tackling substance use concerns.”

Dave added: “We are trying to save lives out there – those in their 30s or 40s who have been traumatised and have gone through real challenges in life.

“If you start to create a generation of young people that are engaged and motivated, I believe in 10 or 15 years Scotland is in a very different position that it is in now.”

For more information on the YiIM and the Stirling University project on how it could work in Dundee, visit the SSA’s dedicated website.