What topic is currently dominating the political agenda in Britain?

Outside Scotland, it is probably the resignation of David Cameron as an MP, the proposed reintroduction of grammar schools, or the ups and downs of the Labour leadership contest.

Such is the nature of politics that other matters may have grabbed the headlines by the time you read this.

Here in Scotland, though, there is only one real subject. The characters may alter from time to time but the plot remains the same.

Since the Nationalists gained an overall majority in 2011, this has been independence, with the prospect of a second referendum being a recurring sub-plot ever since the first referendum produced a conclusive (or so we hoped) No vote.

This Sunday it will be two years since that historic ballot and it would be normal to reflect on its implications and how it helped Scotland reassess her priorities and then move on.

However, the moving on bit never happened and so here we are, not looking back at a past event that shaped our present but stuck in a time warp of constitutional uncertainty.

We were solemnly promised that our democratic decision on September 18 2014 would be binding but it was Alex Salmond doing the promising – enough said. Roll on two years and a new leader has found a new reason to keep the old debate going.

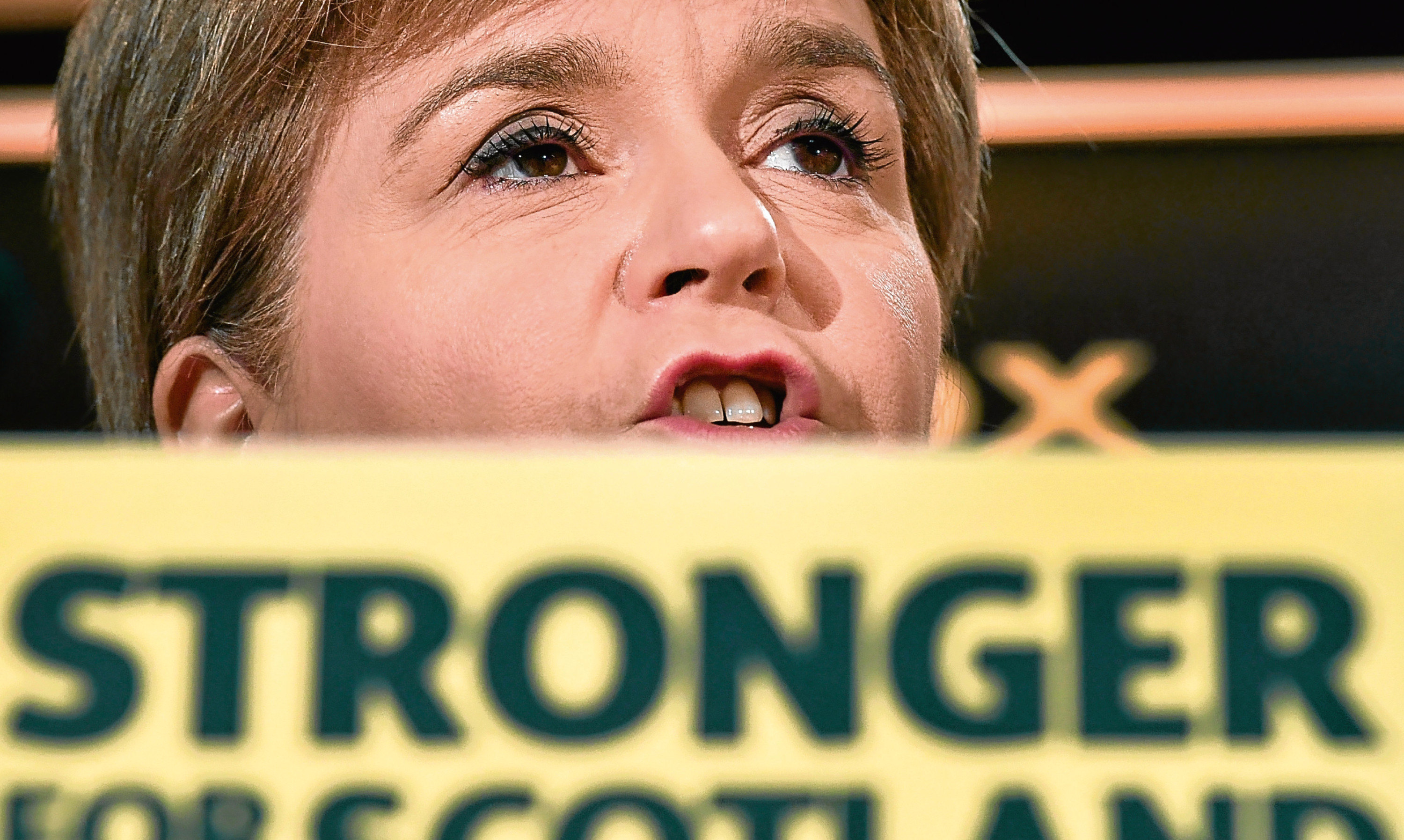

Nicola Sturgeon, having fired up the SNP’s 100,000 members with post-Brexit indignation, has recently tried to play for more time.

When she announced her legislative programme a week ago she could have included a bill on a second independence referendum but she chose instead to call it a consultation on a draft bill.

This will still embroil civil servants in much unnecessary paper pushing but it is something of a retreat for Sturgeon.

She has seen the polls, which put support for independence about back where it was when the Yes camp lost in 2014.

She has also perhaps noted the £15 billion black hole in Scotland’s accounts and realised she will have to wait a little longer to fulfil her separatist dreams.

However, her restraint does not seem to have filtered through to her grassroots and there is apparently a momentum building among Yes groups that indyref two is imminent. Sturgeon will have to deal with their heightened expectations at her autumn conference next month.

That is her problem, not Scotland’s. But what is a huge concern for the rest of us is the effect of the Nationalists’ single issue obsession.

If we try to gauge the Scottish government’s achievements in the past 24 months it is difficult to point to anything of lasting and tangible benefit to the country.

Apart from succeeding in getting themselves reelected in May – albeit with a reduced majority – and winning an incredible haul of 56 seats at the Westminster election in 2015, the SNP’s record in office since 2014 is marked by what it has not done.

It has not reduced the deficit (see above) or grown the economy. It has not closed the education attainment gap, improved poor children’s access to university, shortened hospital waiting times, or indeed introduced any far-reaching domestic reforms.

Policy initiatives such as the controversial Named Persons scheme – designed to assign every child a state guardian – were so badly thought through that they have had to be abandoned in their original form.

Sensible voices, most recently within the business community, have now spoken up and urged the government to drop its independence drive and focus on getting the most from post-EU negotiations.

The UK economy – say the former leaders of the CBI and Enterprise Scotland, senior accountants and private sector bosses – is worth far more to Scotland than Europe’s single market and should not be jeopardised.

In the absence of any action plan from the SNP, it is the Scottish Conservatives’ Ruth Davidson who has put together a task force to explore the future economic landscape.

This includes those who voted to remain in the EU, as well as Leavers but all will concentrate on the “risks and opportunities of Brexit for Scotland”, said Davidson on Monday.

Scottish fishing leaders have already held meetings with UK ministers and so have whisky chiefs, rather than wait for the Scottish government to fight their corners.

Scots do not want to leave the United Kingdom any more now than they did in 2014 and despite being largely pro-Europe, do not regard Brexit as a reason for breaking up the more valuable Union.

Support for another referendum continues to decline, with only 37% in favour, suggesting that even among Yes voters there is no great enthusiasm for a rerun of 2014.

Sturgeon said she was launching a “listening exercise” but she must now accept what she hears.