The role of head teacher demands certain skills, one would assume, with leadership perhaps being the most important.

How strange then that anyone applying for such a position in Scottish schools will soon have to take a special test just to prove they are leader material.

What kind of candidates have been appointed to these jobs to date to make such a measure necessary?

The answer to this is evident in the latest international statistics on education performance, which cast Scotland in a very poor light indeed.

It has long been a cause for national shame that Scotland, a country with record levels of public spending, lags behind not only England but nations such as Slovenia.

Worst ratings ever

However, figures published last week by the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) show Scottish schools dropping even further down the global league table, with its worst ratings ever.

In reading, maths and science, Scotland has declined compared to other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, no longer performing above the international average in any subject.

Scotland’s overall ranking has dropped from 11th to 23rd for reading since 2006, from 11th to 24th for maths, and from 10th to 19th for science.

The SNP cannot shoulder all the blame since previous administrations also presided over plummeting standards and also failed to stop the rot.

In fact, the much derided Curriculum for Excellence, although championed by the Nationalists, was the “brainwave” of the last Labour/Lib Dem coalition.

Nevertheless, the SNP has been in power for nearly 10 years and it has only very recently admitted there is a problem with schools here.

Can ministers sleep at night when they calculate how many children they have let down in that period? Do they convince themselves that their fruitless pursuit of independence justified sacrificing the hopes of an entire generation?

Nicola Sturgeon did vow to make education – or at least closing the attainment gap between rich and poor kids, which is embarrassingly high for a socialist regime – a priority when she succeeded Alex Salmond.

We now realise she wasn’t serious because she has, since then, been interested in the same single issue that preoccupied her predecessor – and it certainly isn’t education.

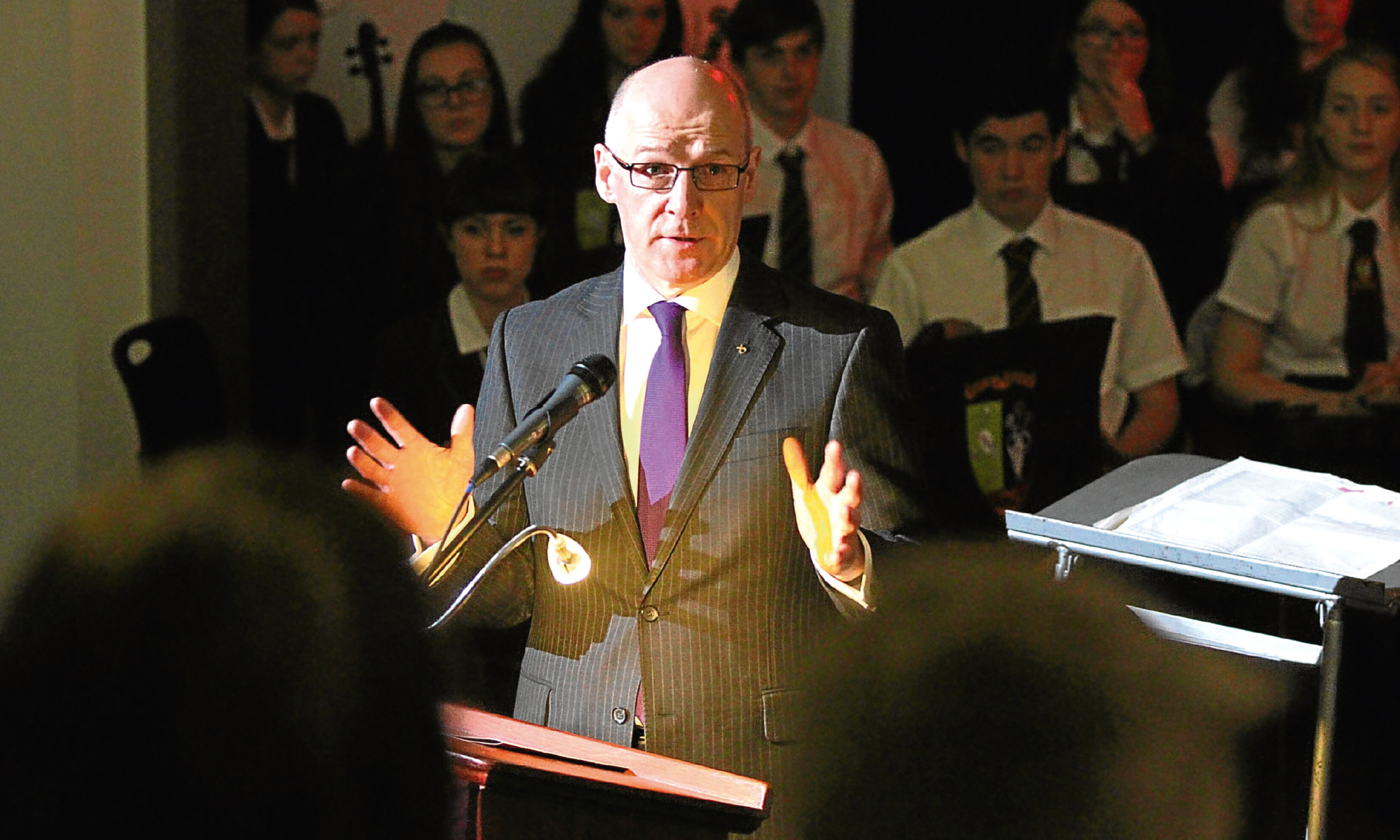

However, she did appoint John Swinney to oversee the schools portfolio after the Scottish election this year and it’s not too late for him to buck the trend of lacklustre and, there’s no other word for it, cowardly Scottish education ministers. But he has to be bold.

Radical reform

Swinney said the PISA results “underline the case for radical reform of Scotland’s education system” but setting tests for head teachers is not radical.

The move will not be retrospective, so there won’t even be a mechanism for removing existing heads of failing institutions.

However, the fact that he uses the word “radical” in relation to schools is unprecedented in Scotland and, therefore, cause for optimism.

He has promised “increased devolution” in schools and this must mean a severing of the stranglehold of local authorities, officials at St Andrew’s House and the unions.

The latter predictably dismissed the PISA findings last week, saying they have previously been misrepresented “by those seeking to make political capital out of talking down education”.

Refusing to acknowledge that Scotland’s system is in trouble has long been the default setting for the education industry, with disastrous consequences for young people, as revealed by PISA.

Swinney cannot be radical and at the same time allow the education establishment to dictate policy, as it has to every Scottish schools minister so far.

Its purpose is to preserve the status quo and since his is, hopefully, the exact opposite, he must show who is boss.

The PISA tests demonstrated that in affluent countries spending more money on schools brings no improvement. What does seem to work, though, is exposure to good teaching more often.

In places plagued by teachers’strikes, such as the Argentinean capital Buenos Aires, the government improved pay and training, treating staff like professionals. The city saw the biggest rise in PISA scores of any area.

In America, where many schools in big cities have been given greater autonomy under the charter system, the influence of family background on test scores fell by more than in any other OECD country over the past decade.

The excuse – used by successive administrations here – that poverty is to blame for poor achievement is blown apart. Likewise, in autonomous inner city London academies, lack of privilege no longer guarantees lack of opportunity.

These examples illustrate simple principles, none of which should be beyond a politician of Swinney’s calibre.

If he really wants to give Scottish children a better start in life, there are ample templates from around the world – from Estonia to Korea – on how to do it. What is he waiting for?