Artist and poet Alec Finlay is on a mission to make wild places accessible for everyone. Gayle Ritchie finds out more about his

latest groundbreaking project…

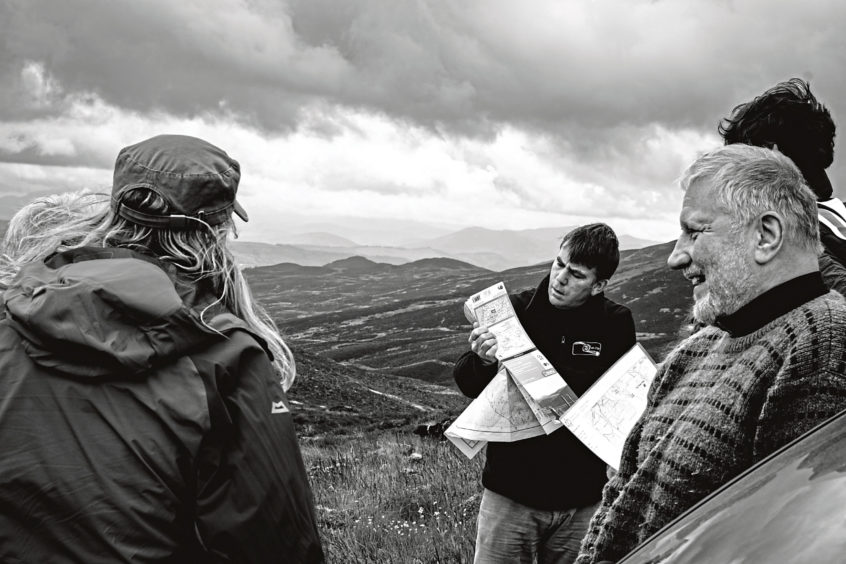

Standing near the grassy summit of 787m Meall Tairneachan in Highland Perthshire, Alec Finlay drank in the breathtaking views across to neighbouring hills and forests.

The smell of damp moss filled his nostrils as he breathed in deeply and took a moment to simply reflect on what was around him – tantalising glimpses of the iconic peak of Schiehallion, the faint hum of insects rising up from the valley below, a pair of buzzards floating lazily on thermals.

It had been a long time since Alec, 53, had been up a mountain.

After being diagnosed with chronic fatigue (ME) when he was 21, he focused on creating art and poetry and didn’t dwell too much on whether scaling a Corbett or a Munro might benefit his health and wellbeing.

“It’s not that easy getting up a hill when you have ME,” he reflects. “But the more I thought about it, the more I became aware of how hill tracks were never used for disabled access.

“Ultimately, I realised that the chronically ill are among those most alienated from wild nature.”

And yet, here was Alec, chronically ill, up a hill, in wild nature.

It was an occasion he had been planning for months – an inaugural, national Day of Access – and it was a day he now hopes will become an annual fixture across estates in the UK.

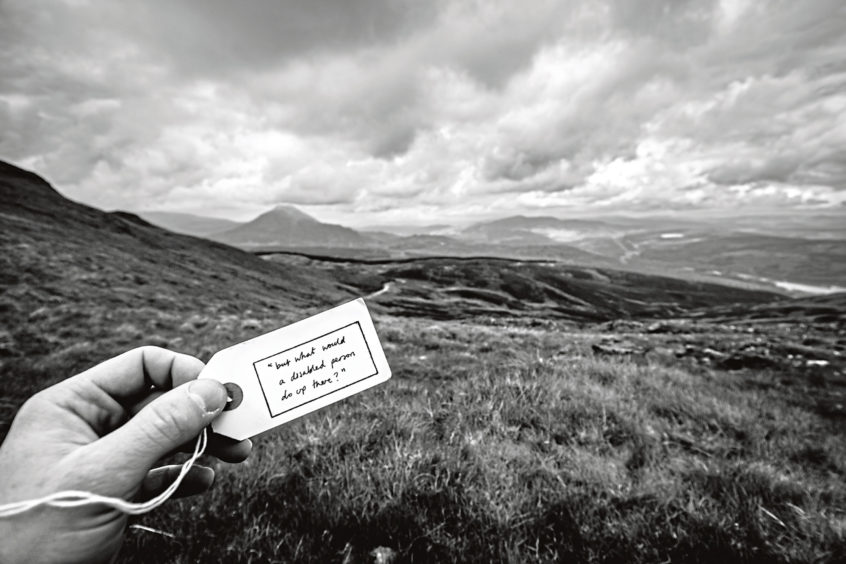

One of Alec’s main motivations for planning the day was hearing a friend relate an off-the-cuff remark from a land owner who proclaimed: “Why would a disabled person want to go into the hills? What would they do up there?”

“Being able to go for a walk in the wilderness is something those who are able-bodied and in good health take for granted,” he says. “It’s an entirely different matter, however, if your ability to walk is constrained.”

The pilot Day of Access took place in June, with Alec taking on the role of activist and encouraging estates to open their land and tracks for people affected by disability and chronic illness to get out into the hills.

It was to be documented by two young photographers, Sam McDiarmid and Mhairi Law, and the resulting images, word-maps, artwork and poetry, would appear in a travelling gallery.

The group consisted of disabled people, photographers, law-makers and estate workers.

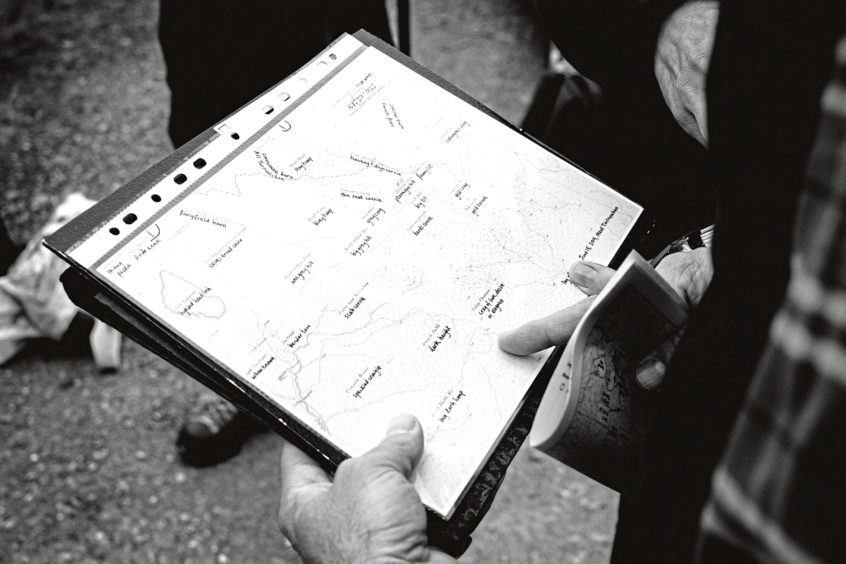

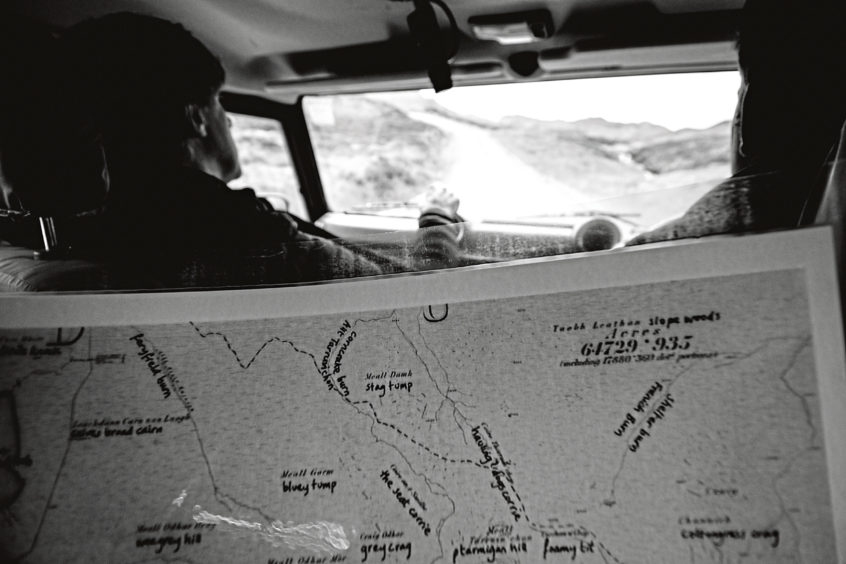

They were driven up the slopes of Meall Tairneachan on undulating, rocky moors between Aberfeldy and Loch Tay in an off-road vehicle and over the course of the day, shared knowledge, studied the history of the land, its place names and meanings, and sketched an “ecopoetic” map of the heart of Scotland, as well as creating works of “ecopoetics” – poetry with a strong ecological emphasis.

Ultimately, the trip was a boost to everyone’s spirits – a boost to their mental health and wellbeing – as well as spotlighting disability perspectives of landscape.

“In Day of Access, the poorly carry limits with them in their legs, but their eyes are free to wander,” muses Alec.

“The trip was fantastic. The views, the company, the connections, the joy of doing something some of us are never usually able to do – it was something fresh, a highlight of the year.

“I’d never fully addressed how chronic illness has shaped my creativity; how closely being limited and imagination relate to one another.”

The event was supported by Forestry and Land Scotland, the John Muir Trust, Heart of Scotland Forestry Partnership and Dalchosnie and Kynachan Estates.

If such events are to become a regular occurrence, and indeed if Alec’s dream to make them happen at public and private estates in 2020, ultimately becoming a dedicated Month of Access across the UK every June, he will need the support of government bodies, estates, and the public themselves.

Before that happens, perceptions need to change. The negative stereotype that all disabled people would be better off sat at home and have no desire to head to the wilderness needs to be turned on its head.

“I’d love it if estates got on board and took people to the hills in 4x4s every June,” says Alec. “I’d love it if that became the norm. It’s about making a change in the world. In a dream world, it might even be written into planning law. I want to make a movement of it. It would be a bit like the open gardens scheme, with estates saying, ‘we’re open for a day of access’.”

ALEC’S ART

Through photography, drawings, manifestos, word-maps, place-name “visual poems” and other slightly off-the-wall artforms such as “blanket landscapes” which use bedding to suggest hilly landscapes, Alec has spent years creating virtual, alternative, ways to further access into the wilderness.

These offer him and others with chronic illnesses or disabilities links, albeit via the imagination, to a wild landscape they would otherwise struggle to reach.

However, the Day of Access allowed a more physical and visceral form of art and poetry to evolve as participants could physically see, hear, smell, touch and experience the landscape around them. As such, their musings and artistic interpretations took on greater meaning, as they were truly immersed in the rawness of the wilderness.

Alongside documentation, word-maps, and photographs from the pilot Day of Access, Alec will exhibit his drawings, sculptures and poems about chronic pain and landscapes at a travelling gallery on tour across Scotland. It’s in various venues across Dundee as part of the digital arts festival NEoN (North East of North) from November 4 to 7.

He describes this as a “bit like a poetic campaign vehicle – a gallery bus”.

There will also be a selection of work from invited artists and poets, including Mhairi Law, Alison Lloyd and Hannah Devereux.

The work is corroboratively displayed like a scrap book or diary pinned on a garden trellis, alongside other domestic apparatus and soft furnishings, such as blankets, and a clothes-horse with hankies. There will also be workshops around disability.

At the back of the gallery there’s a bed-like space where pillows hold audio by Rachel Smith, a dancer who has written dance movements for the bed-bound. Rachel has also collaborated with Alec and photographer Hannah Devereux to create “Counterpane blanket landscapes”, which take inspiration from Robert Louis Stevenson’s poem The Land of Counterpane, remembering childhood illness, where bedding becomes an imaginative landscape. All artworks in the exhibition ask viewers to consider the confines of home and how disabilities frustrate, but also can heighten and enhance the imagination.

CHRIS’S TALE

Edinburgh-based artist Chris Dooks was among those who took part in the pilot Day of Access.

In 1998, Chris – who had been a TV director on the South Bank Show – became ill with ME. Exhausted and in pain, he was forced to give up his burgeoning career, scale down his activity and become an independent artist.

“In the first 10 years of ME, I wasted a lot of time waiting to get better,” recalls the 48-year-old.

“That’s the natural impulse, isn’t it? Curl up, head down, let the storm pass. But what if it’s like one of those 200-year storms on Jupiter?

“In the second half of my ME career – and it is a career – I decided to be ill in other places. I’ve passed out in Amsterdam, been removed from planes in Edinburgh thanks to panic attacks, and cycled 22 miles to Rosslyn, which was my equivalent of scaling Kilimanjaro!”

Chris, a research fellow at Edinburgh University who specialises in the subject of exhaustion-related art forms – “it’s a zeitgeisty thing!” – was delighted to join “other professional exhaustives” for the Day of Access.

“Pumped full of codeine and carbs, I was taken higher than I’d possibly be able to reach, unaided,” he says.

“I got my camera out and shot 200 images in a well-practices burst of energy efficacy.”

Chris is passionate about the concept of the “right to be ill elsewhere”.

“It’s part of the right to roam, in my view. Usually the ill have to be creative and make those lost horizons appear in some alchemical event at home. But every now and then I’m awed by a simple lift up a simple hill by someone who cares.”

Another reason dad-of-two Chris is so passionate about access to wild places for all is that he has a disabled five-year-old daughter, Oona.

She has a syndrome similar to cerebral palsy, uses a specialist wheelchair, fronts a campaign for disabled models and has her own Instagram page, @littleredwheelchair.

“I’m all into doing things and going places like mountains with Oona, even if that means carrying her,” says Chris.

“But what do you do if you’re disabled at Glenshee, for example. You can walk and ski but what if you have a wheelchair? Where can you go that’s accessible? That’s what Day of Access – which is a bit like Doors Open Day – is all about. It’s such a small thing to most people but to see Schiehallion up close was quite a treat.

“It’s a very simple idea that someone else is giving you access up a forestry road, but that’s what drew me to Perthshire from Edinburgh for the day.

“It doesn’t take much effort for others to take you up a hill. I just think it’s a human right to wander and explore and when that right is removed, other illnesses creep in. Day of Access is one foot in the right direction in terms of changing culture.”

BOB’S STORY

Bob Benson, the chairman of Loch Rannoch Conservation Association, and his wife Annie are passionate about access issues.

“The wonders of the natural world have an enormous impact on everybody, but those who are ill, have mobility issues, mental health problems or are recovering find it makes a huge difference to get out into wild places, but they need support to get there and overcome barriers,” says Bob, who walks with sticks and callipers having had polio – which affected the function and growth of his legs – as a child.

“I’ve lived and struggled with my impairment all my life. However, I don’t feel vulnerable, damaged or broken by it; I just want equality.

“The real issue is about inequality of opportunity and access and overcoming barriers society often puts in our way, whether it be to employment, transport or access to the countryside.”

Bob, who was director of Disability Rights Commission Scotland, and a member of the Equality and Human Rights Commission, says fighting for rights is “in his DNA”.

“It’s incredible that some landowners put up barriers and question why disabled people would want to have access to the hills.

“Public bodies need to do their duties around access but some councils are just not willing, despite the fact there’s funding. Getting out into the wilderness – seeing, smelling and hearing all the sights, sounds and aromas of nature – has a hugely positive impact on wellbeing, and why should disabled people miss out?”

Bob found the Day of Access a “tremendous experience” reinforced by the range of conversations about woodland remediation – reversing the damage done to the environment – and funding to save special places and open them up to more people.

info

Alec Finlay is on the hunt for partners across the UK who can fund the Day of Access project in 2020 and provide venues, vehicles, and drivers, as well as participants.

The events are for anyone who has difficulty accessing hills, including disabled, those with chronic illness, pain, or constrained walking.

Travelling gallery will be at Dundee’s Boomerang Community Centre on November 4, Morrisons on Afton Way on November 5, Baldragon Academy on November 6, and the Wellgate Centre on November 7. alecfinlay.com