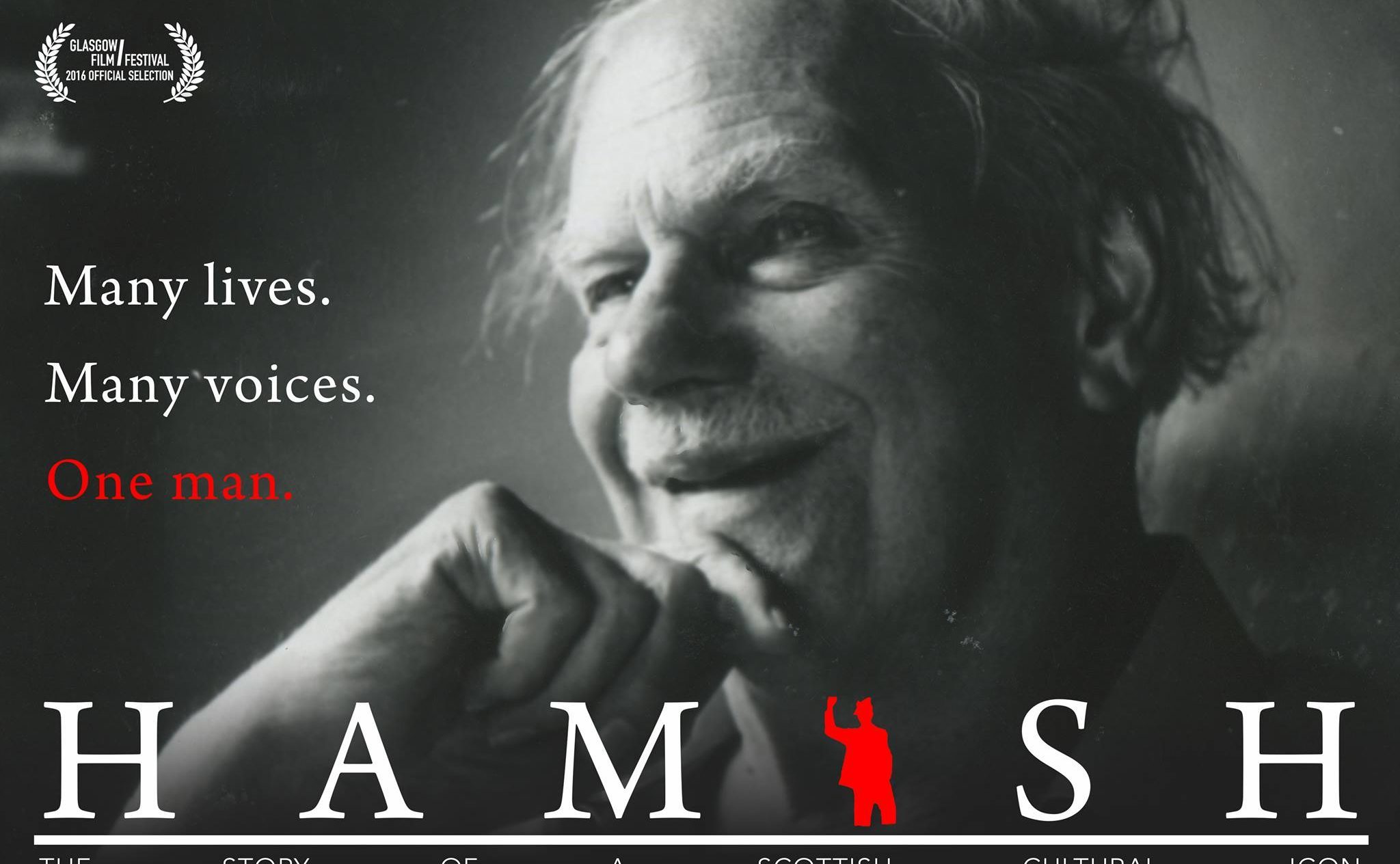

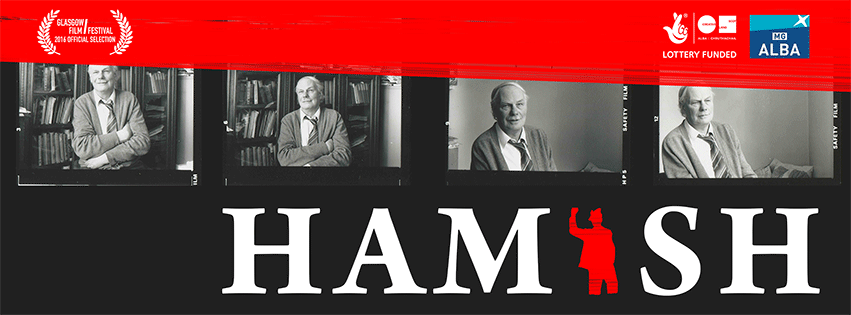

Ahead of its screening in Courier Country cinemas, Michael Alexander speaks to Robbie Fraser, the director of Hamish – a movie which charts the life of Perthshire-born war hero, poet and songwriter Hamish Henderson

Like many people in Scotland, film-maker Robbie Fraser had dim memories of who Perthshire-born Scottish cultural colossus Hamish Henderson was. But he had never fully engaged with his material or found out anything about the man himself.

That all changed, however, when he was working on a documentary in Mali about a gold miner with a Scottish wife from Fife. At a time when music was banned by Islamic terrorists, Robbie’s sister sent him a copy of Henderson’s famed Scottish ballad ‘Freedom Come All Ye’ – a folk song that some say should be Scotland’s real national anthem.

“I listened to it over and over again,” Robbie, 43, tells The Courier. “It’s a real anti-imperial anthem. It’s the opposite of Scotland the Brave. I think it’s even more relevant in the world we live in today. To paraphrase another Scottish legend, ‘We are all Jock Tamson’s bairns’.”

Following its sold-out premiere at the 2016 Glasgow Film Festival, Hamish, Robbie’s much-anticipated documentary about Hamish Henderson, will tour cinemas across Scotland from June 3.

Blairgowrie-born Henderson (1919-2002) was a hugely influential part of Scotland’s cultural scene.

Hamish pays tribute to the many contrary forces and diverse facets of Henderson’s life as a poet, soldier, intellectual, activist, songwriter and leading force of the revival of Scottish folk music.

From an English orphanage and the draughty corridors of Cambridge to overseeing the capitulation of the Italian army in the Second World War, this is Henderson’s life told by those who knew him best and loved him most.

“The way it’s been done is a wee bit unusual in that there’s no voice-over, “explains Robbie.

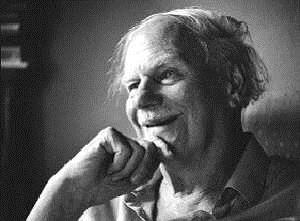

“It’s been a privilege to work on the film because he’s a wee bit lost right now, faded from view. But he needs to be re-cemented into the Scottish imagination as a poet, a maker and an inspirer of people.”

Robbie says it has been a “very emotional film” to work on, and that comes in part because the story is told only through the words of people who knew him personally over many years.

“I’m pretty much the only person on the production who didn’t know him, “adds Robbie, “and I wish I had. He was clearly a benevolent, adored and empowering cultural force.”

It was a particular coup to hear from Hamish’s widow and daughters. He also got on board writer, film-maker and art historian Timothy Neat of Wormit. He wrote Henderson’s biography and gave the film maker exclusive access to stills and video footage.

“It was a steep learning curve, and a daunting responsibility trying to carry on the spirit of who he was, “adds Robbie. “But we’ve given it our best shot and I hope we’ve captured the spirit of the man.”

Born to a single mother on November 11, 1919, in Blairgowrie, Hamish Henderson attended Blairgowrie High School before moving to England with his mother who died before he started school at Dulwich College, London.

Living in an orphanage, Hamish managed to secure a place at Cambridge where he would study modern languages.

While a student visiting Germany he acted as a courier for a Quaker network which helped refugees escape the Nazi regime, later serving with Intelligence Corp in Europe and North Africa as a translator.

His experience of war acted as a catalyst for his poem sequence Elegies For The Dead In Cyrenaica for which he received the Somerset Maugham Award in 1949.

He used his prize money to fund his journey to Italy where he translated The Prison Letters Of Antonio Gramsci; given the sensitivity of the subject, it wasn’t published until years later and he was asked to leave the country.

Henderson became an integral part of the Scottish folk movement when he accompanied the American folklorist Alan Lomax on a collection tour of Scotland.

His career as a collector not only established his place as a permanent member of staff at the School of Scottish Studies but also led him to return to his native Blairgowrie, making the travellers who berry-picked in the summer his particular area of activity.

He beautifully described this time as “like sitting under Niagara Falls with a tin can”

Henderson helped establish the Edinburgh People’s Festival in 1951. It put traditional Scottish folk music on a public stage for the first time and arguably evolved into the internationally celebrated Edinburgh Festival Fringe as we know it today.

As folk clubs sprung up and modern folk songs bled into the mainstream, often these songs contained political themes and Henderson’s own compositions Freedom Come Aa Ye and The John MacLean March were written in to the fabric of Scottish culture.

In 1983 he turned down an OBE in protest of the nuclear arms policy under the Thatcher government and as a result was voted Scot Of The Year by BBC Radio Scotland listeners.

He was openly bisexual and campaigned for equal rights, Scottish independence and was a strong supporter of the release of Nelson Mandela.

*Hamish is screened at Perth Playhouse from June 3 to 7 and at DCA Dundee on June 5

malexander@thecourier.co.uk