From growing up in the Western Isles to playing in a band with Peter Capaldi, Michael Alexander speaks to Roddy Murray whose new book gives an unfiltered take on Scottish life that challenges our tendency to glorify the ups and bury the downs.

Roddy Murray has many stories to tell about a “life full of mishaps”.

They range from fishing in the endless rain as a boy to appalling seasickness and hung-over teenage days in the docks on the Isle of Lewis.

But it’s his recollections of the time he played in a punk band with future Doctor Who star Peter Capaldi and future CBS late night talk show host Craig Ferguson that folk tend to get excited about.

Joining the band

Roddy was just weeks into his first term at Glasgow School of Art in the late 1970s when he saw a notice inviting would-be actors to take part in a theatre production of Frankenstein.

He went along, as he puts it “to try and meet people. To be sociable. To make an effort”.

It was a level playing field of potential.

But it’s also where he met Capaldi – “a compelling, gregarious figure in a long dark coat and trailing scarf” – who was going to be the leading man.

The project’s mastermind was Iain McCaig, who would one day go on to work for George Lucas as a conceptual designer, famously on the Star Wars prequel The Phantom Menace.

Iain had grandiose ideas for the play.

One day, he announced that there was going to be a fundraising concert for the production and they would form a band.

Roddy was recruited, with his basic skill set and the plexiglass guitar he’d bought in Aberdeen a couple of years before.

Peter, meanwhile, was to be the front man, Iain would be the drummer, and John Rogan from Glasgow’s East End was brought in on bass.

Needless to say, Frankenstein never came to life.

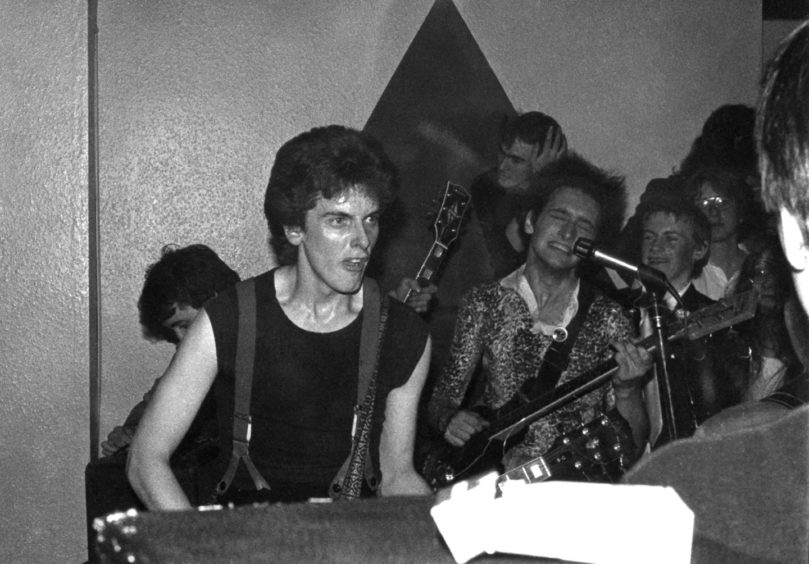

But the band enjoyed a couple of incarnations. Their first gig, as ‘The Ba*tards from Hell’, was during Activities Week in February 1978, when the art school staged events, film, happenings and the like.

Free-for-all

Roddy recalls a “sweaty, beer-soaked, bawls-out, cacophonous free-for-all, devoid of much musical merit but utterly exhilarating”.

The set list was a “dog’s dinner of covers, culminating with John bawling out Pretty Vacant”.

The band, who later recruited Craig Ferguson on drums, attempted to become more serious as “The Dreamboys” before disappearing into what Capaldi has since described as “the ruins of youthful delusion, much of which I don’t remember.”

More than 40 years on, Roddy laughs that he was the only person in the band who didn’t “make it” as a celebrity.

But as the now 65-year-old father-of-two school age children recounts the story with dry wit and humour alongside many others in his recently released book Bleak: A Mundane Comedy, he tells The Courier that, on reflection, the truth is, deep down, he never wanted fame.

“As you get older you do realise certain things, “he says.

“Like being in a band, you are trying to ‘make it’ and become some kind of celebrity.

“Further on you look back and think I didn’t want that at all. I don’t want that. Maybe in a way that’s why I never got that because actually deep down you never wanted it in the first place. I’m much more an introvert than I am an extrovert.

“Some people crave and need to be in the public eye, in the glare of publicity. But that doesn’t do it for me.”

Dry humour

Roddy is bemoaning the Scottish weather when The Courier calls him at home on the Isle of Lewis.

Not only did he have to cancel a holiday he and his family had planned in Nairn after the accommodation fell through, it turns out the weather has been “naff” during the two-week “staycation” his family are having in the islands instead.

The pandemic meant that in his day job as founding director and Head of Visual Art and Literature at An Lanntair arts centre in Stornoway, everything came to a “grinding halt” very quickly in March 2020.

They’ve been picking up the pieces through sheer perseverance ever since. “It’s a typical story,” he concedes.

Yet it quickly becomes apparent that Roddy’s self-deprecating dry humour that is so relatable during these pandemic times is just how he is.

Island life

Born at home in the village of Coll, Roddy describes his upbringing as “absolutely normal” because he had nothing to compare it with.

Growing up seven miles from Stornoway, he describes it as a “genuine way of life” where fishing and the Harris Tweed industry ruled.

While his dad’s parents were from Stornoway, him and his siblings only literally went into town a handful of times a year.

It was a relatively remote existence. Very few people had cars and, because Harris and the islands to the south were at that time part of Inverness-shire, most children there his own age went to schools on the mainland.

However, life was what it was, and while sometimes “bleak” as the name of the book suggests, he reflects on the ironic value of an oft forgotten way of life with “shafts of sunlight” thrown in for good measure.

One fond sardonic memory is a daily diet of herring. He describes his mother as an “exceptional cook”. Potted herring, salted herring, you name it – she would cook it.

“It’s weird looking back that the diet we had back then is what people aspire to today,” he says, “in the sense that everything was organic and locally sourced. Posh food would be when you got tinned peaches on a Sunday!”

As part of a remote island community, the sea was never far away.

Yet recounting another story, amid the mosaic of vignettes and minor personal fables that are strangely relatable, he still finds it “baffling” as to why, when he was about eight, his parents thought it a good idea to take him and his three young siblings on a near 24-hour round trip to Mallaig on the Loch Seaforth.

Sea-sickness

Memories of exhaustion and an encroaching queasiness remain vivid before sickness broke inside him “like a malignant egg”.

“It was a rite of passage, indeed,” he reflects. “And I’ve never been seasick since!”

Roddy only visited the mainland a couple of times on holiday before his mid-teens.

However, if you got qualifications at school, it was a “given” in those days that you would leave the islands to enter further education and that you might only return if you qualified as a minister, doctor, lawyer or teacher.

Roddy took a different path. He went to Gray’s School of Art in Aberdeen for a year “by default”. It was a time when art was “not regarded as a serious subject”, and he had no desire to be a teacher.

“I remember coming in on the train into Aberdeen thinking ‘this is ridiculous, all these houses’. It was astonishing!” he says.

However, he also describes his year in Aberdeen as “a failure and a very steep learning curve”.

While some of his friends from Lewis went into Aberdeen city centre every day for their business studies and other core courses, he had to travel out to the art school campus alone at Garthdee and found the experience “alienating”.

“I left Aberdeen after a year – I just thought I can’t hack this,” he says.

“I went home for a couple of years trying to do the job thing – building sites, power station work, the harbour.

“But I got a real telling off from one of the guys who I worked with in the harbour.

“I met him afterwards in a pub somewhere and told him I had left. He was furious. Did I appreciate the opportunity that I’d thrown away?

“The penny dropped maybe this needs a rethink. I need to give it a second go.”

Glasgow School of Art

By the time Roddy applied to Glasgow School of Art, he felt “battle hardened”.

He’d stay in the city for another five years – punk band experiences and the rest – before moving back to Lewis in 1982.

After a couple of further false starts, Roddy got his first “serious job” with An Lanntair in 1985 through the then Manpower Services Commission and has grown with the organisation since.

The last time he saw Peter Capaldi was in 2010 when he came to Stornoway to help with a fundraiser for the arts centre.

He had no intention to write a book. However, he was persuaded to do so after a chat with a writer friend.

He concluded: “I’d rather it was done first hand by me rather than me off loading all my information and having it reinterpreted by someone else.”

Roddy hopes the stories are relatable. He’s a firm believer that through humour you can get to the truth.

But if there’s one thing he embodies, it’s the ability to laugh in the face of adversity, or even just embarrassment.

Bleak by R.M. Murray is published by Saraband, priced £9.99

ISBN: 9781912235605