A Perthshire-born minister’s invention in the 19th century is helping NASA develop the future of space travel. Here, Michael Alexander speaks to Montrose author Phillip (Pip) Hills about his new book that explores the remarkable tale.

It reads like the plot of a science fiction novel.

The often overlooked and misunderstood work of a 19th century Scottish inventor being adapted to power 21st century space flight and facilitate human missions to Mars.

But if truth is stranger than fiction, then the story of Perthshire-born minister Robert Stirling, whose 200 year-old invention has recently been adapted by NASA, has proved that his creation was centuries ahead of its time.

What is a Stirling engine?

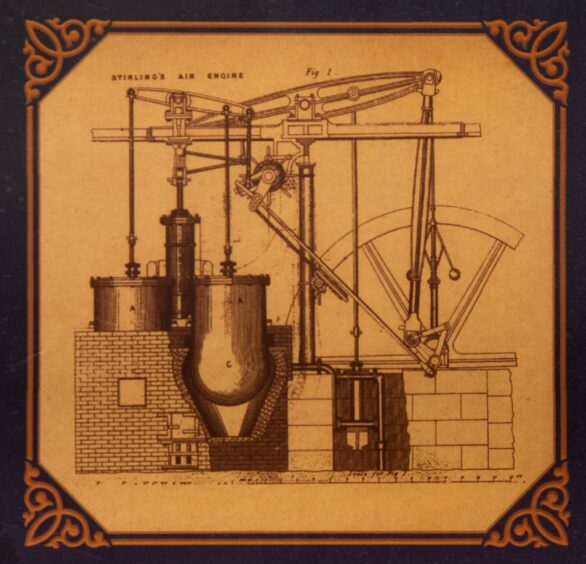

The story begins in 1816, with Robert Stirling’s original design for a heat exchange engine.

Born in Perthshire in 1790, and trained as a Church of Scotland minister after studies, including physics, at Edinburgh University, Robert worked closely with his brother to develop and refine hot air engine technology, which later became known as a ‘Stirling’ engine.

Unlike a conventional engine, a Stirling engine is powered by hot air rather than steam.

The air is alternatively heated and cooled, so that the expansion caused by the heating drives a piston.

Stirling engines are noted for their efficiency, quiet operation, and ease with which they can use almost any heat source.

Yet the practical application of the Stirling engine has taxed the minds of scientists and inventors for almost 200 years.

While one was built to run the Dundee Foundry in the 1830s, for example, it eventually burnt itself out.

It’s only relatively recently, after the ground-breaking work of US scientist William Beale in the late 20th century, that it’s been possible for the Stirling engine’s full potential to be realised.

In 2018, NASA announced the successful test-run of their tiny nuclear reactor KRUSTY.

This revolutionary technology, which runs on heat alone, now powers missions to deep space and may have far-reaching consequences for energy supply on Earth.

The Scottish connection is in the acronym: KRUSTY stands for Kilowatt Reactor Using Stirling TechnologY.

Inspiration for book

Pip Hills, of Montrose, who founded the Scottish Malt Whisky Society in the 1980s, became interested in Stirling technology when he found a model of a Stirling engine in London’s Portobello Road Market.

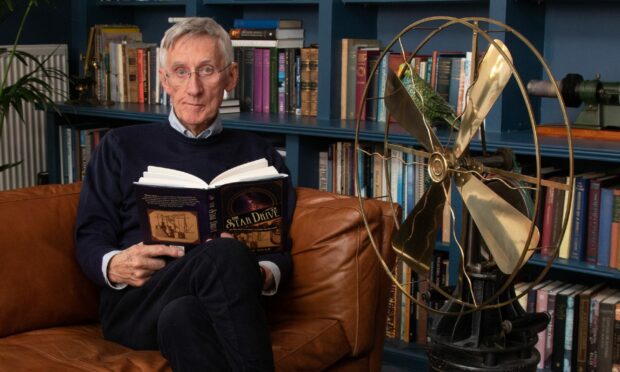

Now, after learning of the recent NASA developments, he has written a book, The Star Drive, telling the remarkable story both of Stirling’s life and the afterlife of his invention.

Weaving together science and history, it is a tale of genius, frustration, and perseverance on both sides of the Atlantic.

“I can’t remember where I discovered Stirling engines, but I do remember very clearly where I first met one, and that was on Portobello Road in London,” says Pip, 81, in an interview with The Courier.

“I was there with my brother in law Dick. One fine Friday morning, we were at a stall with lots of bits of machinery on it and on the ground was another bit.

“I said to the guy ‘do you mind if I pick that up?’. He said ‘no’. I looked at this thing – Dick says ‘what is it’? I says ‘I don’t know, but I think it’s a Stirling engine’.

“I’d only ever read about them, never seen one. I asked the guy ‘how much do you want for it’? He said ‘£240’. I said ‘that’s out of the question’. He says ‘the lady in the shop behind will take a credit card’. I thought ‘I’ll be in trouble’!”

Pip and his brother-in-law took a taxi with the purchase back to their residence in Camden.

Not quite sure what to do with it, Pip put the engine on the gas stove, lit one of the burners and squirted oil into it.

As it got hotter and hotter there was a burning smell. Then, eventually, a fly wheel gave a twitch and it started to turn.

“Dick said ‘why is it doing that’?,” recalls Pip.

“And I said ‘I don’t know’! Because it’s completely opaque technology!

“What in fact was happening is there are generally two cylinders to a Stirling engine.

“One of which has a tight closely fitting piston. The other has a large piston that doesn’t quite fit. The two are connected by a crank shaft on which sits a fly wheel.

“The gas inside the engine is contained. It’s not open to the elements. What happens is when the end of one of the cylinders heats up, the air inside expands and creates a positive pressure which pushes the piston.

“The power piston turns the fly wheel, the fly wheel shaft turns the other non-fitting piston which squirts the air from the hot end up to the cold end of the cylinder where it loses its heat and contracts, and it sucks the piston back in. That’s the basic cycle, although it took me 15 years to get my head around it!”

Renewed interest

There was some interest in the Stirling engine for domestic use but by the early 1900s it was widely replaced by affordable electric motors.

By the 1930s, the Stirling engine was largely forgotten.

In recent decades, however, it has been trialled for use in hybrid electric cars, has been successfully used to power submarines, and can be driven in reverse to operate portable refrigeration systems.

It’s potential as a clean, efficient and reliable source of power has increased interest in recent years due to its compatibility with renewable energy sources.

Placed at the focus of a parabolic mirror, a Stirling engine can convert solar energy to electrical energy and huge Stirling dish plants have been created in hot areas such as Phoenix, Arizona.

Philosophy of science

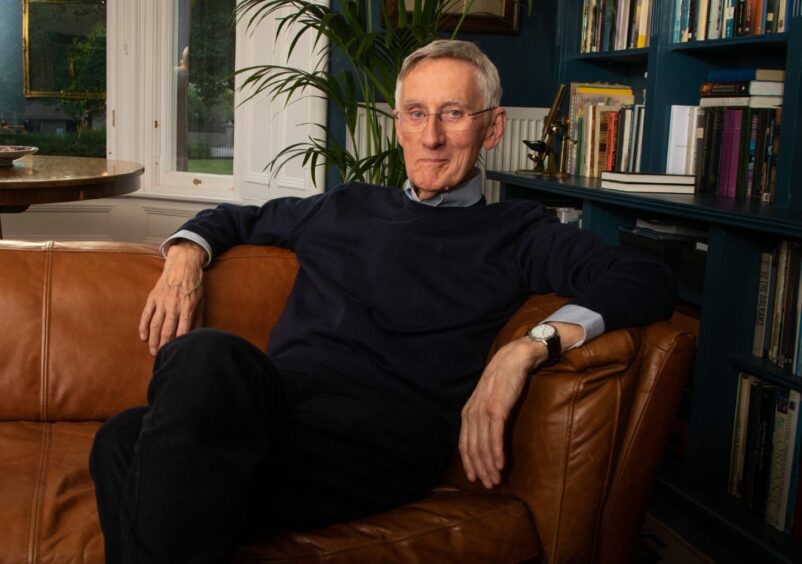

A philosopher by education who had worked as a docker, crane driver, truck driver, tax inspector and accountant, it was something that had fascinated Pip for a long time.

The impetus to write the book, however, came just a couple of years ago when he discovered Stirling technology was being trialled by NASA.

“The advance in the design of the engine was made by an engineer called William Beale in Athens, Ohio, in the 1970s,” explains Pip.

“He invented the free piston Stirling engine. Basically it’s a Stirling engine that has no external moving parts.

“This thing can be configured as a line alternator. Power can be got out of it by electrical means.

“It is the highest of high tech. It’s basically a tube with two pistons inside it. The rest of the space in the tube is taken up by helium at 600 atmospheres pressure.

“It’s just amazing. The work on this for a good many years was funded by NASA because NASA had long term projects to do with sending ships out to the outer planets. They needed a way of propelling it.”

Space technology

With on-board propulsion systems needing some electricity, Pip explains there have only been two reliable means to date.

One is by solar panels which are bulky and heavy, while the strength of solar radiation diminishes at the square of distance from the sun, meaning it’s impractical beyond Jupiter.

The only alternative to solar panels has been to use radioactive substances whose decay produces heat.

The problem with the decay of plutonium 238, however, is that it’s one of the most toxic substances in the universe, requiring heavy shielding.

KRUSTY came about as NASA investigated alternative sources of electricity for serious space travel.

“KRUSTY is basically a nuclear reactor – a fusion reactor burning uranium 235, that’s about the size of a dustbin,” says Pip.

“On top of the reactor sit eight free piston Stirling engines which generate electricity, and on top of that sits a sort of parasol whose business it is to disseminate the waste heat, because Stirling engines need to not only be supplied by heat but have it taken away.

“The plan is to use that as the power source for a Mars based mission.”

Pip says the propulsion of spacecraft is another vexed matter. All spacecraft until now have been propelled by the means of chemical rockets – or “glorified squibs” as he calls them. They are very difficult to control, burn up very quickly and are not much use for steering.

It again became apparent to NASA that this is no good for long term projects.

That’s where the Stirling engine again comes in. He adds: “There’s a system known as ions propulsion which consists of taking an inert gas, xenon is most used because it’s heavy, and putting high charges of electricity into it which split up its atoms into positive and negative ions.

“You can then use the positive ions to squirt out the back of your spacecraft and you have a highly controllable and reliable form of propulsion and steering.

“The plan is to put that together with the Stirling powered generators.”

Scottish invention

Pip says that as a nation, Scotland has been much given for “trumpeting ourselves and saying how much of the modern world derives from what the Scots did”.

Until fairly recently, that’s been fair enough, he says. But no one seems to know about the Stirling engine!

The Star Drive: The True Story of a Genius, an Engine and our Future by Phillip Hills is out now, published by Birlinn, £14.99.