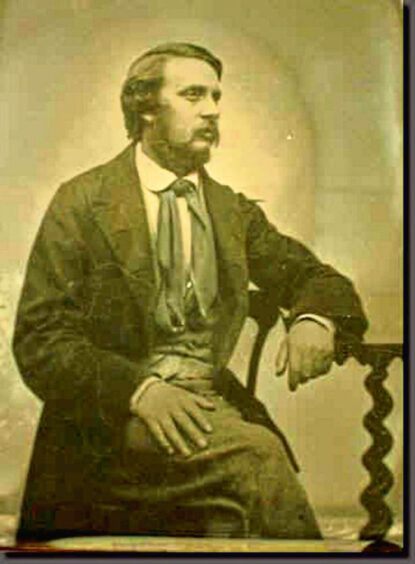

In the bitterly cold winter of 1852, a young man – a mysterious foreigner – restlessly paced the streets of Dundee, dreaming of moving on to greener pastures.

Emile L’Angelier, a Channel Islands native of French descent, was an ordinary worker at a city plant nursery who harboured ambitions to move in high class circles.

Bored with his mundane life and unsuccessful with the local women, he would soon move to Glasgow where he would embark on a clandestine affair with prominent Scottish socialite Madeleine Smith.

A fatal attraction

It was a decision that would prove fatal. Just a few years later, the 30-something Emile would die of arsenic poisoning. Madeleine would be accused of his murder in what became known as the “trial of the century” from which she would, controversially, walk free.

Thousands of people gathered outside the courtroom, while the public galleries were packed with spectators. Newspapers across the whole of the UK reported every morsel of information.

A compelling story

The story had it all – forbidden love, class conflict, blackmail, revenge, a love triangle and most sensational of all, letters detailing the pair’s trysts which were read out in court and scandalised Scottish Victorian society.

So what actually happened?

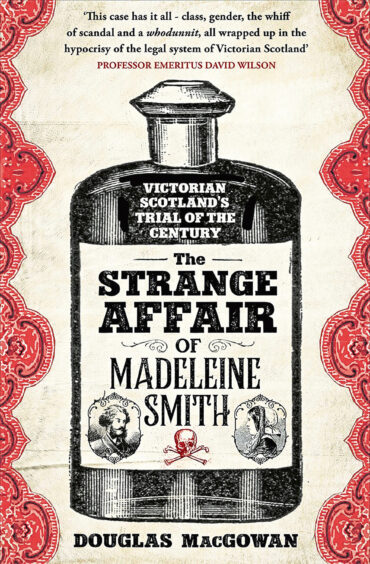

The Strange Affair of Madeleine Smith, by historic true crime author Douglas MacGowan, now lays bare the whole saga including the infamous letters, the pathology reports and the trial testimony.

The Strange Affair of Madeleine Smith

We learn how Emile relentlessly pursued Madeleine after catching a glimpse of her in the street in Glasgow, leading to the pair falling in love. But Madeleine’s father, a prominent architect and a man of fierce temper, would not even hear of his daughter marrying a lowly clerk.

The couple met in secret, with Madeleine talking to Emile out of her bedroom window at night or sneaking out of the house to meet him. She knew, however, that the relationship had to end when a marriage proposal from a wealthy Glasgow merchant came her way.

Her family would never accept Emile as her husband. She would have been cast out from high society unless she married someone of her own class.

Emile L’Angelier: a spurned lover

But Emile wasn’t going to go quietly. In a blackmail attempt reminiscent of today’s “revenge porn”, he threatened to show Madeleine’s letters to her father if she left him – an act that would have had catastrophic consequences for her.

Not only had she disobeyed her parents by continuing the affair, but the letters also mentioned her losing her virginity to Emile, out of wedlock.

Moreover, she had accepted the marriage proposal from the eligible William Minnoch, who had no idea about Emile.

A “ruined” woman

Madeleine’s despair at the threat of the affair coming to light is palpable in her final letters to Emile: “For God’s sake do not send my letters to Papa. It will be an open rupture. I will leave the house. I will die, my father’s wrath will kill me.

“Will you not keep my secret from the world? I shall be undone. I shall be ruined. Shame would be my lot. Despise me, hate me, but make me not the public scandal.”

Shortly afterwards, Madeleine purchased arsenic from an apothecary, saying she needed it to kill rats. But it was Emile who ended up dead, with a large amount of arsenic found in his stomach.

A hunt for the killer

Did she really kill him? There is certainly some evidence to suggest so. She clearly had a motive. But equally, there was a lack of definite information about Emile’s movements during the final hours of his life.

He had exhibited suicidal tendencies and there was some suggestion he had taken arsenic in the past.

As the court couldn’t prove beyond all reasonable doubt that Madeleine had poisoned Emile, the jury returned verdicts of “not guilty” and “not proven” on three charges of murder by administering poison.

“Not proven” verdict

A quirk of Scots law, a verdict of “not proven” is an acquittal, however, some critics suggest its real meaning is closer to “we think you did it, but the prosecution couldn’t prove it”.

“It’s this doubt that has kept people fascinated with this case”, says Douglas, who has researched the story since the 1990s. I still haven’t reached a definite conclusion myself, about whether Madeleine was innocent, or if she did it and got away with it.

“That’s what keeps me coming back. It’s a puzzle with no solution. In the late 90s I thought she had done it but by the 2000s I changed my mind because some new evidence came out. I’ve gone back and forth so much but I still can’t decide. Until I can come to a conclusion the case will continue to fascinate me.”

A long-standing fascination

Douglas, a retired social worker from California, has always been a writer on the side, publishing articles in Scottish-American magazines. He first came across Madeleine’s letters in an archive when he was researching his Scottish ancestry and various other information related to Scotland.

“It caught my interest and I was able to find a book about her in a library in California. It was clear that the case had resonated around the globe. I first wrote an article about Madeleine in 1995 and she has followed me around ever since.

“Although there have been other books written on the case, mine is the first book that includes all of the letters Madeleine wrote, which are central to the case and really fascinating.

A labour of love

“Also, many of the other books are now out of print. I had to go to my local library and put in a special request for them to be transported over from other locations – so they aren’t really accessible unless people know what they’re looking for.

“Other authors take a stand on whether Madeleine was guilty or not, but I don’t do that. I set out all of the evidence and arguments for each side, so that readers can make up their own minds.”

It took Douglas a year to painstakingly go through all of Madeleine’s letters, some of which are held in Stanford University Library, while others are included in court transcripts. Deciphering the letters was no easy task. Bizarrely, once Madeleine finished a page, she wrote on top of the writing once again.

19th century Scotland

The letters are a fascinating window into the everyday life of the Scottish middle and upper classes in the 19th Century.

Madeleine’s life was one of leisure – strolling on Sauchiehall Street, attending balls and concerts, hosting friends at home and spending summers at the family’s holiday home in Helensburgh.

We also get a glimpse of the dynamics of her relationship with Emile, which could be classed as abusive by modern standards.

A toxic relationship

“I think both of them were very controlling of each other,” muses Douglas. “Madeleine couldn’t see Emile publicly but couldn’t give him up either.

“And he was very jealous of her. He didn’t like her to meet friends or go out to balls. Today it would be considered a toxic relationship.

“It seems that he was trying to improve his social position through women. There is mention of a ‘lady from Fife’, who he was involved with for a while. But she eventually married another. We get the impression that she too was several rungs above him in the social ladder.

A social climber

“He was even “shopping around” for churches to go to based on the social class of the congregation. Climbing the social ladder seemed to be his number one priority.

“I don’t think he was a nice person. He threatened to show the letters to Madeleine’s father and that was not a gentlemanly thing to do.

“But if he had burned Madeleine’s letters as she had asked him to, his death would never have been linked to her. There would have been no court case and we wouldn’t even be talking about this today.”

Madeleine Smith’s later life

It is not known whether any descendants of Madeleine live today. After the trial finished and she was released, her engagement to William Minnoch fell through. She married George Wardle, a draughtsman and the business manager of the artist William Morris.

The couple moved away to London and had a son, Thomas and a daughter, Kitten. But after 28 years the marriage broke down. Madeleine emigrated to New York, where she later married a man named William Sheehy.

Her death in 1928 was recorded under the name Lena Wardle Sheehy. It is known she had three grandchildren – Stephen, John and Violet, but after the trail goes cold.

Possible descendants

“There likely are direct descendants living today, somewhere,” speculates Douglas. “Maybe they even know something we don’t, or have some kind of clue. But so far no one has come forward.

“If she ever confided in anyone about what really happened with Emile, then the person never spoke out.

It would be fascinating if any descendants were to come forward. But for now, it looks like it will remain an unsolved puzzle.”