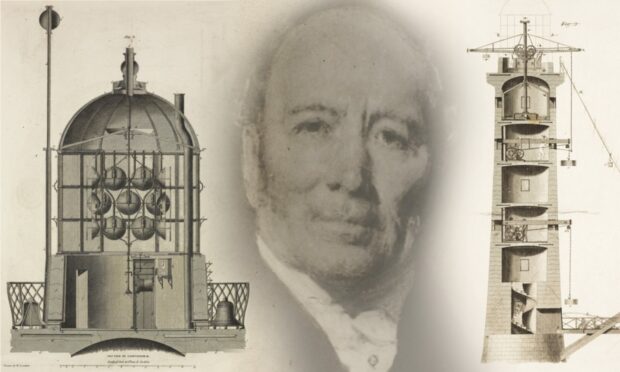

Robert Stevenson has been described as the ‘father of Scottish lighthouses’. As June 8 marks the 250th anniversary of the civil engineer’s birth, Gayle Ritchie chats to experts about his life and legacy.

Adorning Scotland’s wave and wind-battered coast, from the Mull of Galloway to Bell Rock, the Stevenson lighthouses are among the country’s greatest architectural and engineering marvels.

For seafarers, whether at the helm of huge cruise ships or bobbing about in tiny fishing boats, these shining beacons are priceless, and potentially lifesaving gems of navigation. The man responsible for designing and building many of them was Robert Stevenson, grandfather of legendary Scots author Robert Louis Stevenson.

Born into a family that tried to make its fortune from slavery, and destined for a life in the ministry, it was a curious chain of events that put Robert on the path to becoming the true father of Scottish lighthouses.

His remarkable story begins on June 8 1772 with his birth in Glasgow.

Remarkable story

Robert’s father was Alan Stevenson, a partner in a West Indies sugar trading house in the city. Alan died of an epidemic fever a few days shy of Robert’s second birthday, leaving his mother, Jean-Lillie, a widow in dire financial straits.

Robert started his education at a charity school, and Jean-Lillie had high hopes he would join the church.

However, when he was 15, Jean-Lillie remarried and the family moved to a house off the Royal Mile in Edinburgh.

Robert’s step-father was Thomas Smith, a tinsmith, lamp-maker, mechanic, and civil engineer, who had been appointed to the newly formed Northern Lighthouse Board (NLB) in 1786.

Smith took the young Robert into his office and encouraged him to study civil engineering at the Andersonian Institute in Glasgow and later at Edinburgh University.

Apprentice

Serving as an apprentice to his step-father, Robert was so talented that, at the age of just 19, he supervised the construction of a lighthouse on the island of Little Cumbrae in the Firth of Clyde.

He became a fully-fledged lighthouse engineer aged 26, taking on his step-father’s post as engineer to the NLB, an appointment he held for nearly 50 years.

During that time he designed and oversaw the construction of 20 lighthouses round the Scottish coast, the most important of which was the Bell Rock, located on a dangerous reef off the Angus coast.

His many innovations included his choice of light sources and mountings, his reflector design, and his use of rotation and shuttering systems that gave lighthouses unique “characters”, allowing them to be identified by mariners. For this latter innovation, he was awarded a gold medal by the Dutch king.

Hands on

He was known to be exceedingly “hands on” and his work on the Bell Rock and elsewhere offered numerous anecdotes about the dangers he put himself in and his narrow escapes.

In 1799, Robert married his step-sister Jean Smith, and three of their sons, Alan, David and Thomas, along with two grandsons, David Alan and Charles Alexander, became lighthouse engineers – leading to the family becoming known as the Stevenson Dynasty.

The six men, along with Robert’s step-father Thomas Smith, built more than 150 lighthouses in Scotland including the tallest at Skerryvore, the most westerly at Ardnamurchan, and the most northerly, Muckle Flugga, off Unst in Shetland.

Other builds

Robert also branched into other builds, designing bridges including Marykirk Bridge over the River North Esk between Angus and Aberdeenshire. He also improved navigation in the Tay between 1834 and 1842, dredging streams, removing fords and deepening and widening the channel between Perth and Newburgh.

Robert died in 1850, the year his grandson Robert Louis Stevenson was born.

His achievements made their mark on the Treasure Island author who wrote about his grandfather in his unfinished 1896 family history, Records of a Family of Engineers.

Early innovator

Historian Michael Strachan, collections manager at the Museum of Scottish Lighthouses in Fraserburgh, has long been fascinated by Stevenson’s story.

“There’s no doubt that Robert Stevenson is truly the father of Scottish lighthouses,” he says.

“His significance goes far beyond the Bell Rock and other towers built to guard the Scottish coast.

“His personal character shaped the lighthouse service into an ever-improving, sober, respectable and professional service.

“The innovations he made were the building blocks for the Stevenson dynasty and I think it’s impossible to overrate his contribution to the safety of the mariner in Scotland, even today.”

It was Robert who first suggested building a lighthouse on the Inchcape, or Bell Rock, in 1799, a year when 70 ships were lost off the east coast in a terrible storm.

Many doubted that building on a submerged reef 12 miles offshore in the turbulent North Sea would be possible and it wasn’t until 1807 that the political support, finance and plans were in place.

The innovations he made were the building blocks for the Stevenson dynasty and I think it’s impossible to overrate his contribution to the safety of the mariner in Scotland, even today.”

MICHAEL STRACHAN

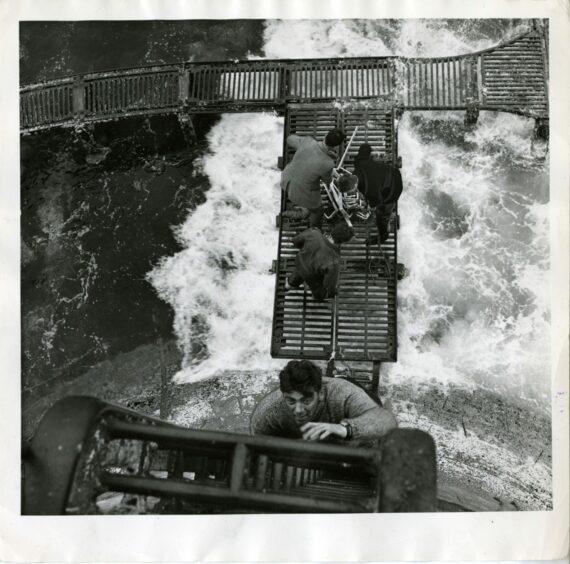

Accounts of the challenges to construct the Bell – tearing out foundations from rock revealed for only a few hours a day to build a 130-foot tower using hand tools and muscle power – make for riveting reading.

But Michael, who wrote a book about Bell Rock in 2018, says Robert’s “force of character, attention to detail, hands-on enthusiasm and the respect of his team” were key to carrying the project to conclusion.

First lit

When the light was first lit on February 1 1811, the Bell Rock became something of a tourist attraction, with Sir Walter Scott famously accompanying Robert on a trip there in 1814.

However, Michael believes that as a historical figure, Robert Stevenson’s legacy has perhaps become too tied up in a single project – as “the man who built the Bell Rock”.

“He was not a modest man – it is clear from his detailed and painstaking personal account of the construction of Scotland’s most famous lighthouse that it was a legacy he wanted for himself, and himself alone,” reflects Michael.

“The Bell Rock was an obsession of Robert’s, both before and after its construction, and to him, perhaps, goes the credit of having the original plan to build a stone tower on the infamous Inchcape Reef.

“His greater achievement and contribution to Scotland was in improving general maritime safety and in saving lives not only by building new lights around a largely untamed coast but also in improving them and leading the way to make the NLB a professional institution.”

Prior to the Bell, the NLB maintained only eight lights around the coast of Scotland with the final three being worked on by Stevenson under his step-father, Thomas Smith.

“Robert had an incredible work ethic and built 18 more lights around Scotland,” says Michael. “Five of those towers were rebuilds; just as he adhered to life-long philosophies of self-improvement, this was applied to his work to bring the early Scottish lighthouses up to a professional standard.

“He replaced three of the NLB’s very first lights at Kinnaird Head, Mull of Kintyre and Eilean Glas and arguably did the same with the antiquated beacon on the Isle of May.”

Legacy tarnished

Michael says Stevenson’s legacy as an inventor and engineering innovator on the world stage has, to some extent, always been tarnished by claims that his inventions belonged to other engineers and, in some cases, were developed by men working under him.

And some question whether chief engineer John Rennie had more to do with the design and construction of the Bell Rock than he has been given credit for.

“It is difficult to sum up Rennie’s contribution in a sentence,” says Michael.

“He was the chief engineer on the projects and made significant changes to the blueprint of the Bell Rock. He was influenced by Smeaton’s argument that the base of the tower should be wider, inspired by the principle shape of the trunk of an oak tree.

“Stevenson’s base was narrower and is claimed would not have been structurally sound against the worst the north sea could offer. In the end the base of the tower was built wider than in Stevenson’s plan, but narrower than in Rennie’s.”

Michael says while there has been counter claim that Stevenson built the lighthouse largely to his own design as resident engineer, author Bella Bathurst points out that he kept Rennie’s attention elsewhere with “constant, absurd questions on the detail”. While Rennie dealt with these, Stevenson built as he saw fit.

“In his own lifetime Rennie was privately critical of Stevenson for claiming the whole credit for the Bell Rock,” says Michael, “going as far as to warn his peers not to correspond with Stevenson suggesting that he would take their ideas and sell them as his own.

“However Stevenson worked tirelessly to improve the technology used in Scotland and it was under his leadership that the old style lamps of Smith were improved with his own Stevenson Reflectors. He introduced rotating and flashing lights to Scotland; sequence flashes of red and white; double lights; and early development of ‘intermittent’ or ‘occulting’ lights.

The father of Scottish light-keeping

“He was the father of Scottish light-keeping, for it was he who created the system of light-keeping used in Scotland for nearly 200 years and adopted by other institutions around the world.

“It was also the paternalistic Stevenson who fought for the rights of early keepers, putting forward a case for pensions for the men who served the lighthouse well but who at the end of their tenure with old age owned not a stick of furniture to their name – the downside of the NLB’s generous settlement to provide tied and furnished housing to their keepers around Scotland.”

Life on Bell Rock

The Bell Rock was a manned light for 177 years until 1988 when the last principal keeper, John Boath, retired.

Referred to as a “temporary Alcatraz” by Michael in his book Bell Rock Lighthouse, it was a lonely and exiled existence for the keeper.

Dundee-born John, 79, would spend up to four weeks stationed there, and recalls he was “never off duty”.

“It was tough. There were more resignations from the Bell Rock than most other postings,” he says.

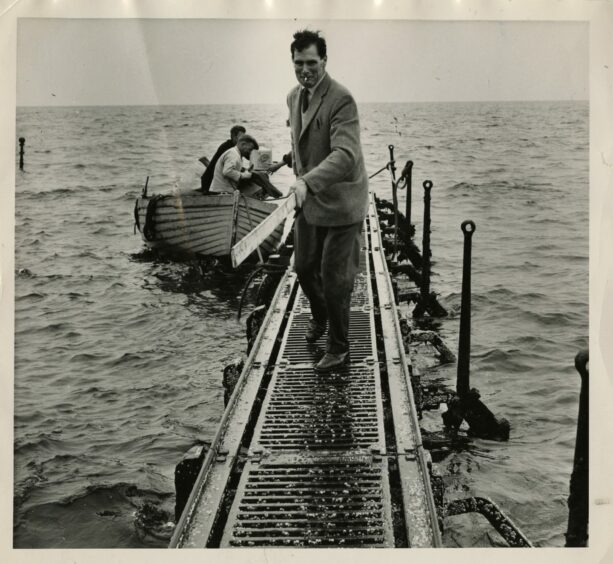

“Visualise landing there in total darkness and freezing cold, with ice sticking to your beard, the boat bobbing about in the sea for an hour before you could get off. Conditions weren’t great; there was no health and safety and hygiene was non-existent. There was no flush toilet, shower or bath. You strip-washed with a sponge.

“If you were caught short when you were up five flights of stairs, you didn’t run down – you did your business and wrapped it in loo paper. Or you peed in a bottle, jar or can, or did it out the window, being careful to clean and scrub it to stop any smells.”

John, who says there was “no room to swing a cat”, recalls sleeping on hard granite stone under blankets, with damp seeping into his bones and engines “going thump, thump, thump 24 hours a day”.

When he wasn’t carrying out maintenance, or ordering paint, diesel and panes of glass, John enjoyed reading, sunbathing and swims in the sea.

“When the tide was out you could walk up and down the little pier to stretch the legs, or I looked for clappy-doos (mussels), or made lobster pots. I was always busy.”

The grandfather-of-ten, who was keeper at the Bell from 1983 to 1988, was sad to leave when it became automated but will never forget his time there.

“The mind boggles when you think Stevenson built such an amazing structure,” he reflects. “It’s not hard to see why it’s been described as one of the Seven Wonders of the Industrial World.”

Building blocks

Dad-of-two Craig Pake has been employed by the NLB since 1998 and has made around 25 trips to the Bell.

The 46-year-old planning engineer is struck by the correlation between Stevenson and his grandson, the writer.

“Some of RL Stevenson’s stories are inspired by trips around the country and to dangerous, inhospitable places,” he says.

“There’s the notion of adventure and bold ideas for both the writer and lighthouse engineer.”

Formerly an electrical engineering technician, most of Craig’s job is now office-based, organising site surveys, although he still makes trips to lighthouses across the country.

“A lot of it is about maintenance and logistics and making sure buildings are sound. I’ve been to the Bell in all weathers and it’s about trying to eliminate risk.

“There can be really bad weather but the Bell’s been built to last! There are times when waves hit the tower and it shudders but it’s the safest place to be.”

It’s rather an adventure getting to the Bell, says Craig.

“When you land by helicopter, everything needs to be winched up – clothes, sleeping bags, pillows, food, tools – and you’re up and down vertical ladders. It’s a really physical role. Everyone takes turns to cook and because it’s such a tight space, you have to keep everything clean and get on with everyone.

“But I’m honoured to have such a great job working on Stevenson structures.”

Top ten Robert Stevenson lighthouses (according to Michael Strachan)

- Bell Rock 1811 (Angus) – Probably the most famous Scottish lighthouse. Named as an industrial wonder of the world, it was Scotland’s first rock lighthouse and is now the oldest surviving sea-washed tower in the world.

2. Isle of May 1816 (Angus) – Built in a gothic-style it departs from Robert’s largely plain, rubble-built structures. The light replaced the antiquated coal beacon which had been working since the 1640s. Some referred to it as the Commissioner’s Lighthouse as it contained a boardroom and lodgings for the commissioner.

3. Kinnaird Head 1823 (Aberdeenshire) – Kinnaird Head was the NLB’s first light, exhibited from 1787 on top of a castle tower. It was drastically improved by Stevenson who brought it to a professional standard by building a new lighthouse through the middle of the castle.

4. Mull of Galloway 1828 (Galloway) – The picturesque light was used by Stevenson to trial his intermittent light, whereby the light was covered and exposed by a set of mechanical blinds. This created a character of light periods and dark periods.

5. Sumburgh Head 1821 (Shetland) – Built on a huge cliff the tower contains only 52 steps. Its foghorn still operates as part of the visitor attraction.

6. Pentland Skerries 1828 (Pentland Firth) – Stevenson superintended the first light at Pentland Skerries in 1793, which almost cost him his life. On his return to Edinburgh his sloop was becalmed causing Stevenson to request to be rowed ashore to Kinnaird Head. Soon after the winds got up, the sloop was blown north and all hands lost. Stevenson rebuilt the towers in 1828.

7. Girdle Ness 1833 (Aberdeenshire) – Unique in Scotland the single tower at Girdle Ness was designed with two lightrooms; one at the top and one mid-way. This caused the light to appear longer vertically when seen at a distance. The lower light was removed in 1890 when the lantern was blocked up.

8. Eilean Glas 1824 (Outer Hebrides) – Originally lit in 1789, Stevenson replaced the old tower in 1824. The remains of the old tower can still be seen beneath the new tower today!

9. Lismore 1833 (Inner Hebrides) – One of Stevenson’s last lighthouses, its first Principal Keeper was Robert Selkirk. Selkirk joined Stevenson during the Bell Rock construction becoming his Principal Builder on the project. He remained with Stevenson building, among others, the new towers at Kinnaird Head and Eilean Glas. His job at Lismore was a reward, presumably when he became too old for the building work!

10. Cape Wrath (Highland) – Well, the name says it all really!