As Dracula marks its 125th anniversary, Gayle Ritchie explores how the north-east was the main inspiration for Bram Stoker’s iconic novel.

Blood-sucking vampires, a creepy castle, a tangled love story – Dracula has been sending thrills of horror down the spines of readers for 125 years.

Even those who’ve never read Bram Stoker’s classic novel are familiar with its most famous incarnation, Count Dracula, and the myriad film and TV adaptations the monstrous, or in some eyes, tragic, figure has spawned.

Scotland played a major role in the creation of the chilling story with Stoker making multiple trips north of the border – most often to Aberdeenshire – for inspiration.

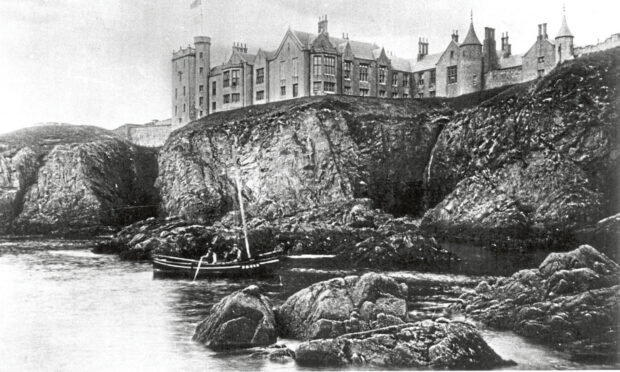

It was Cruden Bay in particular, with its intriguing coastal landscape and dramatic Slains Castle, that drew the author and theatre manager all the way from London by train.

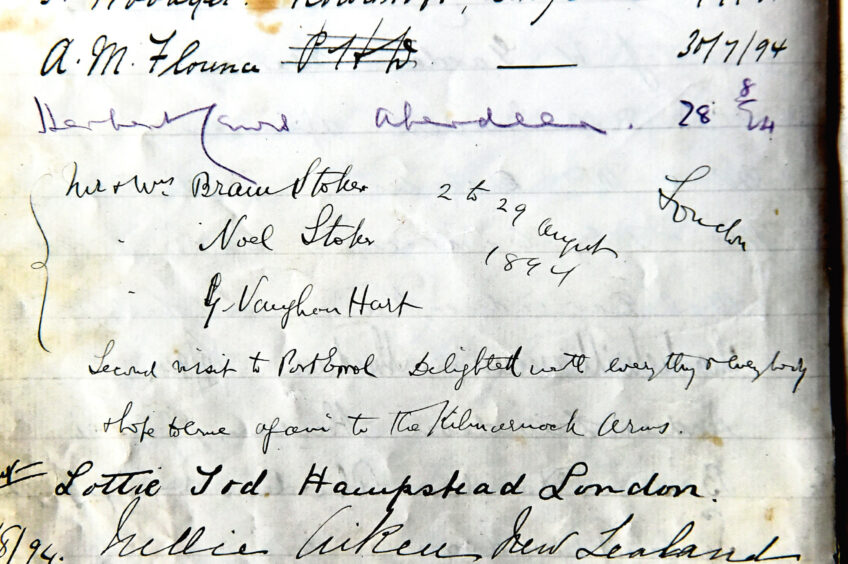

He holidayed in the village at least 12 times between 1892 and 1910, and it was here that he found the solitude, space and atmosphere he needed to become truly inspired.

Booking into the Kilmarnock Arms Hotel with his family in 1895, intent on writing the early chapters of Dracula, Stoker became known for his eccentricities, often perching moodily “like a bat” on a rock as he gazed up at the clifftop castle.

His wife Florence later told biographer Harry Ludlam of her husband’s strange behaviour: “When he was at work on Dracula, we were all frightened of him… he seemed to get obsessed by the spirit of the thing,” she revealed.

“There he would sit for hours, like a great bat, perched on the rocks of the shore, or wander alone up and down the sand hills, thinking it out.”

Stoker’s son, Noel, told Ludlam his father was inclined “to be short-tempered” and “very testy” while working on the novel. This was most unusual – normally the locals regarded him as a “jolly Irish fellow, full of jokes”.

There he would sit for hours, like a great bat, perched on the rocks of the shore, or wander alone up and down the sand hills, thinking it out.”

FLORENCE STOKER

THE STORY

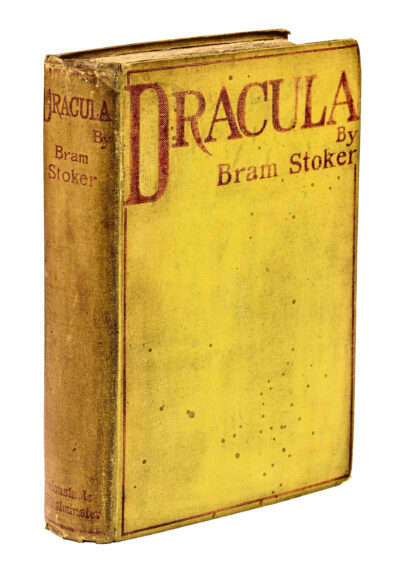

Published in 1897 as an epistolary novel, the narrative of Dracula is related through letters, diary entries, and newspaper articles.

It opens with solicitor Jonathan Harker taking a business trip to stay at the castle of a Transylvanian noble, Count Dracula.

Harker escapes the castle after discovering Dracula is a vampire, and the Count moves to England and goes on to plague the seaside town of Whitby.

A small group led by Van Helsing hunts down Dracula, finds him in his Transylvanian castle, and kills him – although interestingly not with a stake but with a knife, leaving him to crumble to dust.

Mostly written in the 1890s, Stoker produced more than a hundred pages of notes for the novel, drawing extensively from Transylvanian folklore and history. He found the name Dracula in Whitby’s public library while on holiday there, picking it because he thought it meant ‘devil’ in Romanian.

When Dracula was published in 1897, the novel was well-reviewed but sold modestly, leaving Stoker poor by the time of his death in 1912.

However, a stream of adaptations — movies, plays, comics, TV series, books and video games – gave him the potential of an afterlife, and ironically alludes to his having already lived for 500 years or more

CRUDEN BAY CREATION

Stoker had never been to Transylvania when he escaped to immerse himself in the shipwreck-scattered north-east coast of Scotland.

Here he found Dracula’s world of crashing sea, foreboding sky and fang-like rock formations – and a striking castle to boot.

Stoker’s great-grandnephew Dacre, 63, says the concept of Dracula had long been brewing in his famous ancestor’s imagination, but it was in Cruden Bay that it was truly conceived.

Canadian-American author, former pentathlon coach and filmmaker Dacre, 63, has been fascinated by Stoker’s story since he was 12 years old.

He’s written both a prequel to Dracula (Dracul), inspired by notes and texts left behind by the author, and a sequel (Dracula The Undead).

“The north-east of Scotland was really where all Bram’s earlier inspiration and research came together and it’s likely the majority of Dracula was written in Cruden Bay,” he says.

“The area offered him peace and quiet, solitude, atmosphere, inspiration – far from the stress of his job at the Lyceum Theatre in London.

“He chatted to locals and coastguards to get a deeper insight into his surroundings and to listen for any ghostly tales he could incorporate into his writing.”

Dacre says the castle exterior depicted in Dracula draws inspiration from Bran Castle in Transylvania, while the interior portrayed in the novel is inspired by Slains Castle, especially its unique, windowless octagonal chamber, which had only a single lamp to light it and is mentioned in the book.

Stoker was said to have thought Cruden Bay’s beach and rocks were like “fangs rising from the deep water” and was transfixed by the ‘Skares’, jagged rocks that poke out of the North Sea at the south end of Cruden Bay’s beach.

Dacre, who jokingly describes himself as a “bit of a literary forensic detective”, says he hunts down bits and pieces of information about Stoker and tries to draws a conclusion – “a bit like putting a jigsaw together”.

“Bram didn’t leave an autobiography that said, ‘I went to Cruden Bay because of this’. But we have him saying things in newspapers – like that he loved the bracing weather,” he reflects.

“He came here with a map of geological formations in the area. That’s significant because he mentions outcrops of granite and gneiss.

“There’s a line between Cruden Bay and Whinnyfold where the granite stops and this other black rock starts. The red and the black come together. That plays a major role in another of his novel’s, The Mystery of the Sea.”

Underworld of mother nature

Stoker also had a keen interest in the link between the supernatural, the occult, and the “underworld of mother nature”, says Dacre.

“He saw the area as a place where the underworld shows itself. At low tide, you can see the sand crag Bram sat on – he mentions it in his books. He sat there and did his writing.

“Then there’s the Skares, a treacherous rocky reef. Bram was also interested in the horrific nature of all the souls that at died at sea here – the souls not at rest.”

Stoker also stayed in Hilton Cottage in Cruden Bay, Crooked Lum Cottage in the tiny hamlet of Whinnyfold, and was a guest at the Garden Arms Hotel in Gardenstown in 1896, the year before Dracula was published.

“The lady who rented him the Crooked Lum said people were scared of him and the way he would march up and down the beach!” says Dacre.

“This was Bram method-acting, getting into his roles, adopting the persona of Count Dracula.

“He was known as being friendly and upbeat – to have scones and tea out with his wife – not as this scary person. But people here gave him the space to just be.”

DRACULA’S GUEST

Dacre published a special 125th anniversary edition of Dracula – a reprint of the classic vampire novel along with ‘Dracula’s Guest’, included in the original manuscript (but edited out), plus an extended ending to the novel.

“His widow Florence published missing pages from the original draft of Dracula in a short story, Dracula’s Guest, in 1914,” he explains.

“This edition reinstates some of this manuscript as well as including two thirds of a page edited out of the ending which involves a volcanic eruption after Count Dracula was stabbed.”

Dacre says this comes “full circle” to Bram’s fascination with the underworld, connection to the supernatural, and volcanos as the home of the devil.

“Interestingly there’s an extinct volcano in north-east Transylvania – the location of Bram’s fictional castle based on his notes and actual coordinates. He was planning a volcanic eruption at the end of the story but it was crossed out!”

Stabbed

In popular culture it’s widely believed that Dracula had a wooden stake driven through his heart.

But, says Dacre, he was actually stabbed with knives – Harker stabs him in the throat with a kukri knife while Quincey Morris stabs him in the heart with a Bowie knife.

“So who knows, maybe Bram wanted the story to continue at some stage! Because to kill a vampire, you need a stake…”

BLOODLETTING AND VAMPIRISM

Jedburgh-born author Emily Gerard played a huge role in Stoker’s creation of the vampire and all traits associated with vampirism.

“He did a lot of research into vampirism and Gerard’s collections of Transylvanian folklore had a huge influence on him,” says Dacre.

“He mentions, in the only newspaper interview he’s given that anyone’s found, how he found an essay by Gerard about how Romanians believed in vampires, how to use garlic, how to stake them and kill them.”

Sarah Kersh, professor of Victorian literature and culture at Dickinson College in Pennsylvania, believes Dracula sits at “the intersection between the use of blood as both a symbol of traditional superstition and modern medical practice”.

She adds: “The widespread practice of bloodletting, whereby a vein or artery was punctured and blood was drained from the patient to restore the balance of their humors, to prevent illness, lasted well into the 19th Century.”

Dacre thinks there’s a “very good chance” Stoker, who was a very sickly child, was blood-let.

“Nobody knows what caused his seven year illness but we know he did not have a normal childhood,” he muses.

“One of his uncles was a famous doctor who wrote a treatise on blood-letting, so I think there’s a very good chance Bram was blood-let.

“I think that because there is a passage in Dracula where Bram describes Jonathan Harker finding the Count in his crate in Castle Dracula looking ‘bloated in his repletion’ like a leech after a full meal. To be blood-let would be a horrible experience for a young boy: it would’ve had a major impact.”

Crawling out of graves

While he was ill, Stoker’s mother shared her experience of watching apparently dead people crawling out of graves during the cholera outbreak of 1832 – surely traumatic for the young boy to process.

“His mother had witnessed misdiagnosis and premature burial of people,” explains Dacre.

“She described a man going to this mass grave to give his wife a proper send off. She wasn’t dead at all and he had to help her crawl out of all these bodies. Little stories like that may well have had an impact of the young Bram.”

Does Dacre think his great-granduncle believed in vampires? He laughs: “Well, who knows! He was a broad-thinker and a Freemason, which doesn’t mean he was a weird guy who sacrificed cats!

“He was an open-minded man who thought there might be more to life than meets the eye and had a great respect for the occult and spirits of the dead.”

LITERARY LEGACY

Dacre funded and unveiled a plaque commemorating Stoker’s links to the area – and to mark the official 125th anniversary of Dracula in May – on the exterior of Kilmarnock Arms. He hopes this will help establish “some sort of literary legacy” in the area.

“The plaque shows you all the spots where we know Bram stayed, the places he described not only in Dracula but in other books (The Watter’s Mou, The Mystery of the Sea). Places where he set the story,” he says.

A few years ago Dacre, a frequent visitor to Cruden Bay, campaigned for a street in the village to be named Dracula’s Close – “that was a bit tongue-in-cheek!” – but he was happy enough when Aberdeenshire Council settled on Stoker Road.

Stoker’s signatures in the hotel’s guest book, from 1894 and 1895, survive to this day, and a special ‘Stoker’s Snug’ was created in the lounge bar last year.

In what’s arguably a cheeky nod to the north-east, he included the Doric line “I wouldn’t fash masel’” in the sixth chapter of Dracula.

DRACULA HOTSPOTS

Locations in Edinburgh, the Scottish Borders and Glasgow all have links to Stoker.

Renfield Street, Glasgow: Stoker supported the staging of plays at the Glasgow’s Theatre Royal. It’s thought the name of RM Renfield, a character featured in Dracula, was taken from Glasgow’s Renfield Street.

Lyceum Theatre, Edinburgh: Before writing Dracula, Stoker worked as a theatre manager, which saw him heavily involved in the opening night of the Royal Lyceum Theatre in Edinburgh in 1883.

Jedburgh, Scottish Borders: Jedburgh-born author Emily Gerard was the first person to bring the word “nosferatu” or “vampire” into use in western Europe. Her collection of Transylvanian myths and legends are known to have influenced Stoker’s Dracula.

Conversation