A groundbreaking new exhibition at V&A Dundee exploring the history and future of plastic launches on October 29. Curator Laurie Bassam assures Gayle Ritchie that it’s ‘not all doom and gloom’.

Plastic has percolated into every aspect of our existence, shaping our daily lives like no other material.

It’s in our clothing, footwear, household goods, furniture, in our cars, buildings and food packaging.

It’s been drilled into us that plastic is polluting our seas, killing off our wildlife, spreading toxins and contributing to global warming.

However, there’s more to plastic than just doom and gloom. In essence, it’s not simply an “evil” product that’s ruining lives and landscapes.

A symbol of carefree consumerism and revolutionary innovation, it’s spurred the imagination of designers for decades – think cutting-edge pop era fashion, furniture, decor and household goods (Tupperware, Perspex, polystyrene are just a few examples).

Today, however, the dramatic consequences of the plastic boom have become glaringly obvious, and it’s true to say that the material has lost its utopian appeal.

Never has it been more important to understand the 150-year history of the material, understood to be essential and yet superfluous, life-saving but also life-threatening, seductive and yet dangerous.

Reframing our relationship

A new exhibition launching on October 29 at V&A Dundee aims to address the issues around plastic, and to make us reframe our relationship with this much-contested material.

Laurie Bassam, co-curator of Plastic: Remaking Our World, says: “The intention is to make people think about plastics, and their relationship with plastics, rather than feeling very doom and gloom about it.

“It’s about maybe saying – do I really need X amount of plastic in my life, do I need as many toys? Could I use an alternative material? “Could I take a reusable water bottle with me? It’s about small changes.

“There are lots of things people can do to change their relationships with plastics, both as individuals and collectively.

“Can we petition our MPs about use of the material, perhaps? Can we actively help to change the future, even if just in our own small ways?”

Celebration

The exhibition is also very much about celebrating plastics, says Laurie, in terms of its vast uses and design.

“There are some really amazing objects in the show,” they say.

“I think the key is not to make people gloomy about plastics. It’s more about understanding our relationship with a material we find familiar in so many ways.

“It’s also about making people open their eyes and start to question where things they own, and don’t even think about, come from.

“Maybe a child will look at his or her Lego set with fresh eyes.”

150-year history

The exhibition covers the 150-year history of plastic, from the material’s birth in the 19th Century until the present day and how our relationship with it – initially regarding it as a “magical material” – has changed.

“Designers responded to the devastating environmental impact of plastic overproduction with a wave of cutting-edge material experimentation and contemporary design approaches,” says Laurie, V&A Dundee’s assistant curator, and one of a team of seven curators from Vitra Design Museum Germany, V&A London and the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (MAAT) who all worked on the new plastic exhibition.

“Examples of these breakthrough innovations are showcased in the ‘future’ section of the exhibition, where visitors are invited to explore more sustainable uses and alternatives to plastic.”

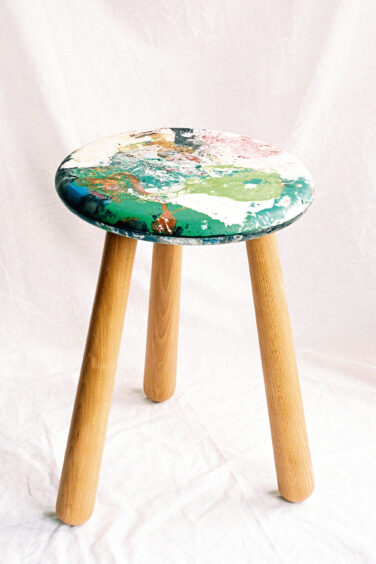

Exhibits include rarities from the dawn of the plastic age and objects from the pop era including fashion, architecture, furniture and product design, through to contemporary designs and projects – from efforts to clean up rivers and oceans, to bioplastics made from algae and mycelium.

The exhibition takes visitors on a three-part journey, beginning with an immersive video installation by Asif Khan Studio, exploring the relationship between plastic and nature.

The second part traces the history of plastic from its natural origins through to synthetic material experimentation in the mid-19th and early 20th Century.

It continues with the rise of the petrochemical industry and its impact on the scale of plastic production as well as the concern for the planet that grew towards the end of the 20th Century.

Finally, the third section examines multiple contemporary approaches to rethink the future of plastic and to ask, what role can design play in tackling the plastic crisis?

Plastic Lab

Laurie is hugely excited about the exhibition’s ‘Plastic Lab’, which boasts a ‘free interactive space’ in which visitors can walk around and explore the ‘promise and problem’ of plastic.

Here they can also witness a ‘precious plastics machine’ in action as it melts objects like milk bottle tops into other items.

And as a nod to the 1970s Energy Crisis board game featured, visitors can play modern climate-inspired board games including Global Warning and What Next?

“It’s a darkened space with big projections,” says Laurie. “It should give visitors a sense of how we’ve got to where we are now.

“The second room, all about synthetics, is a bit like a big department store – maybe a bit like walking into an Apple store.

“There are beautifully intricate objects made from a variety of semi-synthetic plastics, showing how things are not always mass-produced.”

And when it comes to the world of fashion, the exhibition displays some mind-boggling pieces, a dress made out of Second World War parachute nylon being just one example.

There’s also a section dedicated to toys made of plastic, including Barbie dolls and Lego sets, plus a display of comics such as DC Comics’ 1960s Plastic Man.

A section on architecture showcases space-age housing – made using plastic components – and architect Alison and Peter Smithson’s famous 1956 House of the Future design.

Iconic Ball Chair

A major highlight of the exhibition is the swivel Ball Chair by Finnish designer Eero Aarnio – one of the era’s most iconic and symbolic innovations.

An immediate success at the International Furniture Fair Cologne in 1966, the Ball Chair featured in films, showrooms, and on numerous magazine covers, with politicians, pop stars and fashion models all photographed in it.

Aarnio’s cosy private retreat was fitted with a quirky “twisty” red Ericsson telephone, also featured in the exhibition.

Serious messages

While upbeat, colourful, eye-catching and exciting, the exhibition also has several serious messages to relay – about oil production, sustainability, environmental damage, and about how plastic is essential to life.

“We’ve got an incubator on loan from Ninewells and a prosthetic arm from bespoke prosthetic studio, The Alternative Limb,” says Laurie.

“It’s about exploring how plastic can be hugely useful in hospitals, essential for saving lives. It’s better than glass at keeping small babies warm.

The intention is to make people think about plastics, and their relationship with plastics, rather than feeling very doom and gloom about it.”

LAURIE BASSAM

“However, plastic has become over-used in hospitals and there are initiatives even in Ninewells to start reducing reliance on single-use plastics.”

As part of Laurie’s team’s research they worked with students from Dundee University Medical School, alongside Dr Pavan Banaglore and Dr Rodney Mountain to explore plastic waste at the hospital and ask questions about how it could be reduced.

“Dr Bangalore in particular is part of a project exploring the concept of sustainability in surgical theatres,” explains Laurie.

Another issue, when it comes to single-use plastics, is food packaging, such as film used on punnets of grapes.

“It’s about looking at whether things like this could instead be biodegradable,” says Laurie.

Beach finds

Also featured in the show are plastic ‘beach finds’ as well as quirky exhibits from Glasgow’s Plastic Bag Museum from the 1970s to the present day. These single use plastic bags have been collected as pieces of social history.

“It’s about looking at solutions,” says Laurie. “We’re not saying plastic is evil at all.

“There’s a duality about it. It can be really useful. We can explore reusing and recycling or even repairing, buying less and buying more responsibly.

“It’s not a scary, doom-laden subject. It’s just about re-evaluating and reframing our relationship with it.”

History of plastic

We’ve been using plastic-like materials, such as shellac – made from a resin secreted by lac insects – for thousands of years.

But plastics as we know them today are a 20th Century invention.

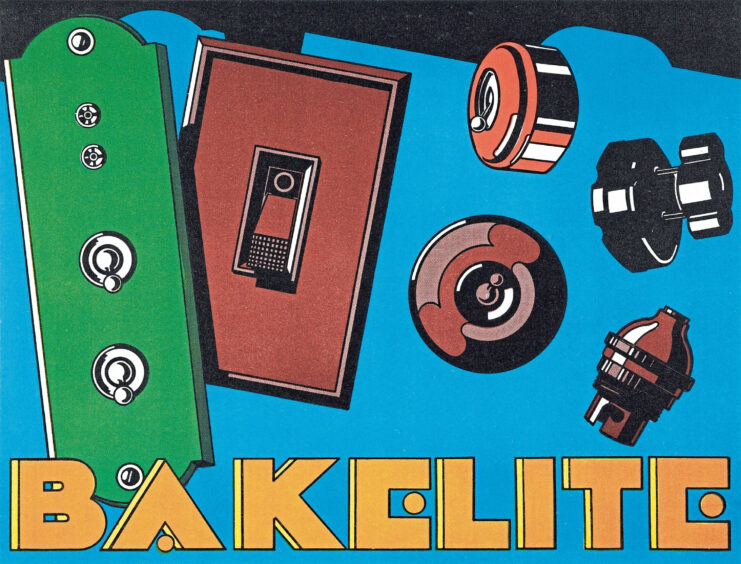

Bakelite, the first plastic made from fossil fuels, was invented in 1907.

But it wasn’t until after the Second World War that production of synthetic plastics for use outside the military really took off.

Since then, plastic production has increased, from two million tonnes in 1950 to 380 million tonnes in 2015.

If it continues at this rate, plastic could account for 20% of oil production by 2050.

Today, the packaging industry is by far the biggest user of virgin plastic – plastic resin that has been newly created from a petrochemical feedstock, such as natural gas or crude oil without any recycled materials.

We also use plastic in buildings, transport, furniture, appliances, TVs, carpets, phones, clothes… it’s everywhere.

And to lose it, in some industries, would be devastating. In hospitals, for example, plastic is used in gloves, tubing, syringes, blood bags, incubators, sample tubes and much more.

Here’s a round-up of some of the quirkiest exhibits…

1. Bakelite leaflet, 1930s

The first fully synthetic plastic, Bakelite, was invented by Belgian-American chemist Leo Baekeland in 1907. Bakelite is made from phenol and formaldehyde – liquid synthetic ingredients that, when poured into a mould, undergo a chemical reaction and solidify into a solid mass. Bakelite was a hugely successful material: its hardness, strength, and fine finish meant that objects previously carved from wood or other hard materials could now be compression-moulded and mass-produced. This innovative plastic was ideal for use in new technologies that emerged at the beginning of the 20th Century, including radios, phones, and other household electrical products.

2. Pineapple syrup bottle, 1958

After the Second World War, the plastics industry searched for new uses for its wartime innovations. Plastics found their way into homes in the form of time-saving devices, easy-to-clean gadgets, and safe, colourful children’s toys. Visually arresting products that were also convenient and affordable came with the promise to make housework and childcare easier and life more carefree.

The first squeeze bottles made from soft polyethylene hit the market in the late 1940s. In the early 1950s, Bill Pugh, a designer at British plastics manufacturer Cascelloid, designed a lemon-shaped squeeze bottle for lemon juice. It was sold by the entrepreneur Edward Hack, who later also patented other fruit-shaped squeeze bottle designs including a banana, a strawberry and a pineapple for different types of fruit syrup to flavour milk.

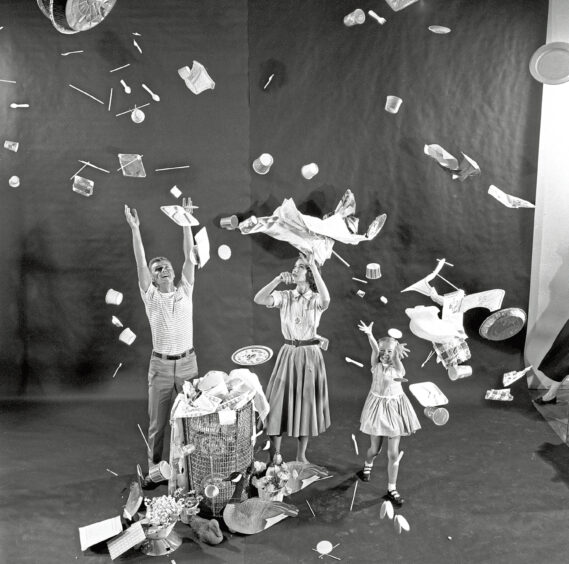

3. Photo by Peter Stackpole to illustrate an article on ‘Throwaway Living’ for LIFE Magazine, August 1, 1955

This iconic image marks the beginning of the throwaway era. The article the photograph illustrated enthusiastically reported that the items depicted “would take 40 hours to clean – except that no housewife need bother. They are all meant to be thrown away after use.”

4. Pallo/Ball chair, 1963. Eero Aarnio for Asko

Plastics gave designers and furniture makers opportunities to experiment with bold colours and new production methods. The Ball Chair by Finnish designer Eero Aarnio is one of the era’s most iconic and symbolic innovations. An immediate success at the International Furniture Fair Cologne in 1965, the Ball Chair featured in films, showrooms, and on numerous magazine covers, with politicians, pop stars and fashion models all photographed in it. The chair became one of the most visible pieces of furniture of the 1960s.

5. Shellworks, jars made from Vivomer, a bioplastic produced with the help of microbes, 2019

Designers, architects, and scientists are exploring how natural materials such as algae, mycelium, and agricultural waste can be used to produce plastics from renewable resources that are biodegradable. Founded in London in 2019, Shellworks began developing a bioplastic from crustacean chitin – a waste product from the seafood industry. In response to the increasing interest in a vegan alternative, Shellworks launched a new material created by microbial fermentation. Vivomer is made by microbes that feed on a carbon source, such as sugar or food waste, and produce a plastic-like material in their cells. The material can be broken down again by microbes.

6. MycoTEX seamless jacket, 2018, Aniela Hoitink. 100% Mycelium

MycoTEX is a manufacturing method for seamless, tailored clothing made from compostable, lab-grown mushroom mycelia. The garments are made by growing mycelia in a mould shaped to create good fit without the need for measuring, cutting, or sewing, so there’s no waste. After use, mycelium products can be broken up and mixed with soil, and they biodegrade in around 60 days.

- Plastic: Remaking Our World, runs at V&A Dundee from October 29 to February 5, 2023. The exhibition is free for 18s and under and supported by Zero Waste Scotland.

- It’s the first international touring exhibition co-produced by V&A Dundee, the Vitra Design Museum and MAAT Lisbon, with curators from V&A South Kensington. Tickets are on sale now at vam.ac.uk/dundee

Conversation