Am I a psychopath?

In an age of endless true crime documentaries, serial killer dramatisations, cold case investigation podcasts and cripplingly self-aware psychology ‘influencers’, it’s a question many of us have asked ourselves.

Indeed, studies have shown that 91% of men and 84% of women have what’s called a ‘vivid murder fantasy’ – we know who we’d kill, with what, and how we’d hide the body.

Is it a case of too many childhood games of Cluedo, or something wired wrong in our minds? How would you know if you had the brain of a ruthless killer?

For serial killer expert Cheish Merryweather, it was the question which kickstarted an entire career.

The research psychologist was just eight years old when she became fascinated with the darker side of human nature.

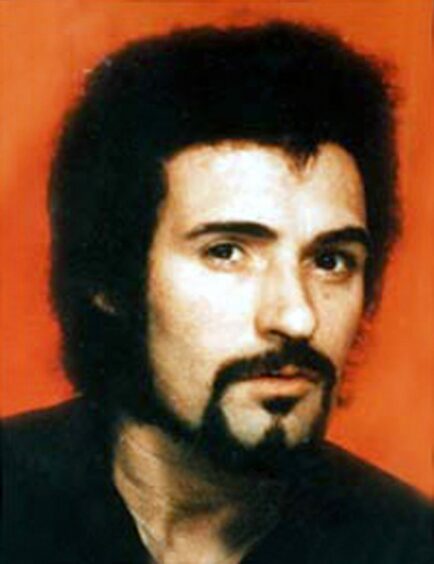

“I read a book on the Yorkshire Ripper and I was absolutely terrified,” recalls Midlands-based Cheish, who was, in her own words “a little freak” as a child.

“And then in the very middle of the book, it went back on his timeline, and it talked about him being a child. I was like, ‘Oh, hold on – I’m a child. And the Yorkshire Ripper was a child?’ It didn’t make sense to me.

“Then I kind of figured it out – the monsters were once children too. And that got me into this web of psychology.”

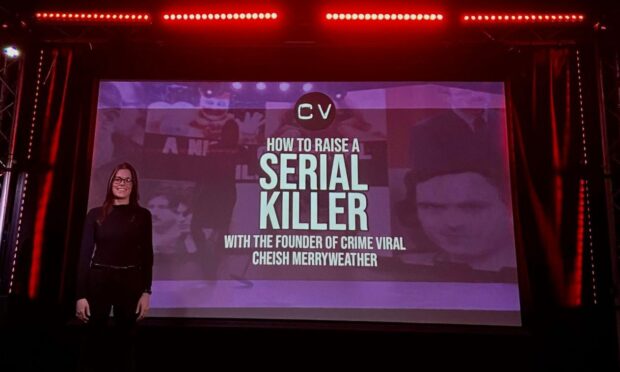

Now, Cheish is the founder and director of Crime Viral, a true crime media community which produces books, podcasts and – most excitingly, for her – touring shows.

Her two-hour Serial Killers and Psychopaths talk covers morbid topics such as ‘serial killer couples’ and ‘the seven steps to true evil’; but by far the biggest draw of the night is the live psychopath testing.

How do you test if someone’s a psychopath?

It’s estimated that around one in 100 people is a psychopath, and every night, Cheish conducts tests on her audience to determine who in the room is high on the psychopathic spectrum.

Going by the numbers, on her upcoming visits to Dundee and Aberdeen, she expects to find three – maybe four – psychopaths.

Sceptical? So was I. So to get a taste of her process, I asked her to test me.

The four tests, based on research by Oxford University professor Dr Kevin Dutton, each look at different aspects of the psychopathic character: ruthlessness, sensation seeking, ability to stay cool and calm under pressure and a test of moral judgement.

Audience members rate how strongly they relate to statements using numbers zero (not at all) to three (strongly relate), and each test is scored out of a total of 33.

Explaining why she’s derived the test in that way, as opposed to more traditional methods of people simply scoring themselves on named personality traits, Cheish notes: “You can ask somebody, ‘Are you callous?’ and they’ll be like, ‘No I don’t think so’.

“Or you could say, ‘Are you ruthless?’ and of course they’ll say, ‘No, I’m not’.

“But if you put it into a personal, social perspective, like: ‘Is it OK to step on others if it means you get ahead professionally?’ then suddenly people start to go, ‘Well… if you want a promotion, maybe…'”

The statements include anything from the seemingly innocuous – “I rarely make plans, I choose my adventure at the beginning of each new day” (2, for me) and “I am able to stay cool and calm in the face of disaster” (also 2) – to more obvious indications of callousness, such as “It’s OK to cheat in relationships as long as your partner doesn’t find out” (0, no bueno).

“That last one’s always tricky if people are out on dates when they come to the tour!” laughs Cheish mischievously.

Explaining the scoring system, she says that below 11 is “incredibly sweet, not a cause for concern” and 12-22 is average.

However, anything above 23 is “quite scary”, as that veers into the realm of psychopathy, while 30-33 would be “a very high level of psychopathy indeed”.

Cheish tests me for ruthlessness, and I score a somewhat disappointingly average 13.

Likewise, Cheish reveals that – to her morbid dismay – she is not a psychopath.

“My score is 16, so on the relatively low side of average,” she says.

“Ideally I’d like to score a lot higher because I think it would be a good twist in the talks where I’m like ‘I’m the psychopath’ but no. I’m sorry to let everybody down!”

Can a true psychopath fool a psychopath test?

The test seems sound, but I do have one gripe with it – if psychopaths are, as their reputation suggests, notoriously narcissistic, self-serving and expert manipulators, wouldn’t they just… lie?

“The true psychopath will pick up from a very young age that they are different,” admits Cheish.

“And rather than making themselves vulnerable to others by showing they’re different, they emulate other people’s emotions. Psychopaths have a very limited range of emotion so to blend in, they mirror the emotions of those around them.”

But, she adds, there are ways to measure psychopathy using physiology, not just psychology.

“Psychopaths have a really low resting heartbeat,” she explains in relation to the ‘staying calm under pressure’ test.

“It takes a lot for them to feel any sort of impending danger or doom. It’s not that they’ve been desensitised – like a lot of firefighters, for example, have taught themselves over time to be desensitised to the danger of their jobs.

“However with a psychopath, they have this natural born ability in the face of danger to just feel no anxiety whatsoever. No spike in their heartrate.”

And heartrate isn’t the only measurable physiological indication of a psychopath.

In fact, psychopathy is “absolutely neurological” and can be identified by brainwaves – or lack of them.

“In an EEG scan, which is what we would do to test your brainwaves and see your neurological wiring, we can actually see the brain wiring of a psychopath,” reveals Cheish.

“There would be little to no activity in the prefrontal cortex, which just sits right at the very forefront of the brain. It’s where your empathy, your insight, and your decision-making process takes place.”

Crucially, it’s that decision-making which differentiates the ‘vivid murder fantasy’ majority of us from the truly murderous minority.

“With the vivid murder fantasy thing, it comes across as if we’re all walking around in society like homicidal maniacs!” exclaims Cheish.

“But thankfully we have that prefrontal cortex where our decision making takes place, and we also have that ability to look forward into the future. We’d be concerned about the consequences.

“A psychopath can visualise the future, but they have no concern for the consequences, and that is how it can all go wrong.”

The psychopathic brain – nature or nurture?

So if psychopathy is neurological, rather than psychological, is psychopathy a case of nature over nurture?

According to Cheish, it’s “a bit of both”.

“If a young child [with a psychopathic brain] has grown up in environment which is full of a lot of love, affection, kindness, encouragement, they will become a pro-social psychopath,” she explains.

“So that’s our bomb disposal technicians, our surgeons, our CEOs. They’ve got that low resting heartbeat, they’ve got the brain of a psychopath, and they can go on to do incredible things.

“But if you take a child, again with a psychopathic brain, and instead they’re raised in an environment of cruelty, neglect and abuse, that psychopathic brain is of course going to go a completely different way – often criminal.”

It’s these criminal stories that we as a society – particularly women – are fascinated by.

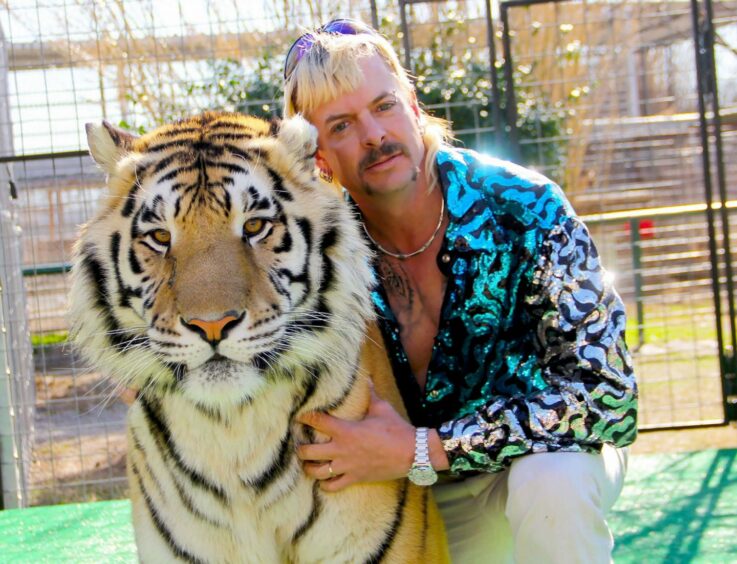

In 2021, it was revealed that true crime was the biggest documentary subgenre offered by streaming giant Netflix, and also the fastest growing one, with programmes like Tiger King dominating viewing charts for record numbers of weeks.

Cheish reckons that the female fascination with true crime makes perfect sense – since notable serial killers most often kill women, they embody “our greatest fear”.

“At all of my talks, about 99% of the audience are women. So I usually open up the talk by saying, ‘to the few gentlemen in the room, welcome to Ladies’ Night, this is how we like to entertain ourselves’,” she laughs.

“It’s about getting as close as we can to our worst fears imagined, but not getting so close that we have to experience the terrifying inconvenience of death itself.”

Why are we obsessed with psychopaths?

But is this mass consumption of real-life terror and trauma healthy? More importantly, is the creation of such content even ethical?

“It’s difficult territory,” admits Cheish, who acknowledges that although she is an academic research psychologist, she’s also an entertainer.

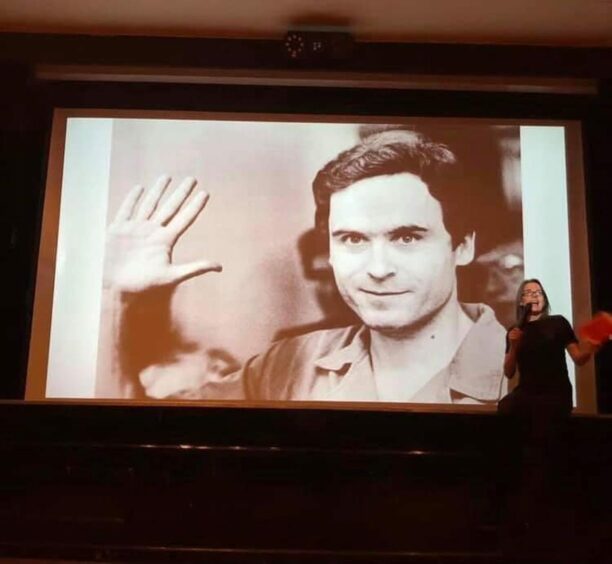

“Not all narcissists are psychopaths, but all psychopaths are narcissists,” she explains.

“So it would really be a serial killer’s worst nightmare if they were to commit their crime and then they just rotted away behind bars. If nobody was interested, there was no detective waiting to interview them, there was no weird fans writing letters, no psychologists asking questions.”

And as well as potentially feeding the egos of career killers, Cheish recognises that true crime content can be “retraumatising” for the families of victims, or survivors.

But she maintains that it can be beneficial for families to know that “something is being done”.

“In the 1980s and 90s, the true crime documentaries… they were just slasher horrors!” she says candidly. “And it was really from the perspectives of the killers themselves.

“Nowadays there’s been this big shift in true crime; there’re more victim-led stories and true crime has become a lot less sensationalised.”

Cheish Merryweather will present Serial Killers and Psychopaths at Dundee’s Gardyne Theatre on June 3. For more information or to book tickets, please visit the Crime Viral website.

Conversation