It’s almost three years since fire ripped through the Scottish Crannog Centre.

Locals watched in horror as the inferno destroyed its showpiece feature – a replica of an Iron Age dwelling house.

The blaze, on June 11, 2021, took just six minutes to tear through the centre’s much-loved icon.

By morning, the wooden structure – that had stood on stilts in Loch Tay near Kenmore for a quarter of a century – was a smouldering wreck.

Mike Benson, the centre’s director, was reduced to tears when he saw the devastation, but his emotions were mixed.

While sad to have lost the crannog, he was relieved nobody had been hurt, and that the museum’s artefacts, some dating back 2,500 years, remained intact.

Almost three years on, a replacement Crannog Centre, on the north side of the loch at Dalerb, is rising from the ashes.

New Scottish Crannog Centre

The new attraction opens to the public on April 1, with a preview for guests on March 31.

Having been invited along for a sneak peek earlier this month, I’m confident the centre will blow visitors away.

For starters, it’s 12 times the size of the old site, and when it’s finished – and it’s getting there fast – it will boast not one but THREE crannogs (reconstructions of stilted loch dwellings).

It’s a wee bit like a construction site when I visit, but Mike assures me things will be ready for the grand opening.

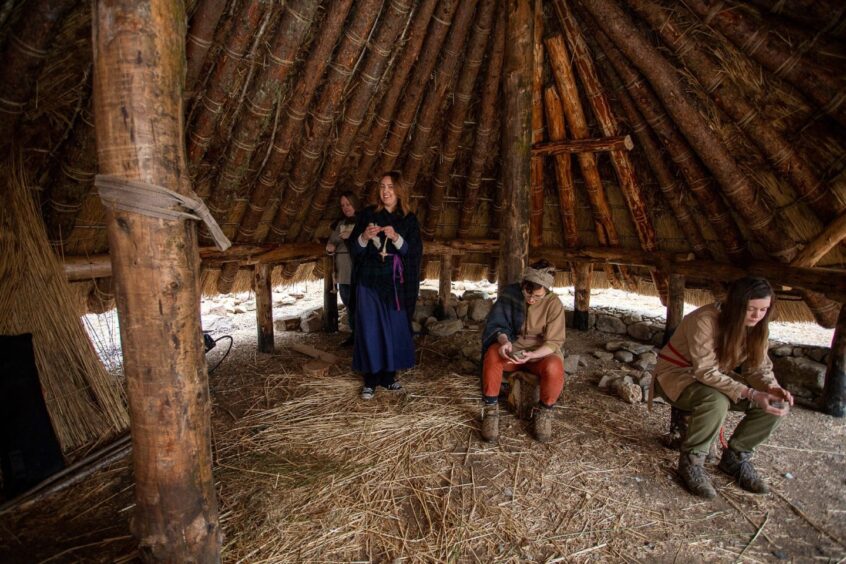

The new centre features an Iron Age settlement, including a fabulous giant roundhouse – woven from hazel branches gathered from nearby trees and resembling an upturned wicker basket.

The site is bustling with activity when I arrive, with craftspeople wielding a variety of tools and making a lot of noise.

Ambitious project

I’m invited into a huge glass building – the centre’s cafe, shop and museum. I’m offered a latte and informed that soon, soup, sandwiches and cakes will be available in this gorgeous, shiny new space.

Then it’s a case of sporting hi-vis gear and heading out to meet the folk at the forefront of this ambitious project.

It’s a jaw-dropping moment as I come face-to-face with the stunning array of buildings on the loch-side site, most of which are crafted using locally-sourced materials, including reeds, hazel, turf, heather and stone.

Rich Hiden, the centre’s assistant director and operations manager, greets me beside a circular drystane dyke.

He’s hugely excited about the future. In his mind, the new museum will be the yin to V&A Dundee’s yang.

Scotland’s most sustainable museum

“We’ve got the same bold ambition as the V&A but believe we can offer a greater sense of place and belonging,” he muses.

“We aim to be Scotland’s most sustainable museum – in touch with prehistory and our roots.

“It’s a fantastic chance to give back to the community, and expand what we had at the old site.”

Rich reveals that the buildings, including two cooking shelters and a roundhouse, will host demonstration workshops, whether baking bread, making jewellery, spinning, wood turning, metalwork, making fires or working with textiles.

And while most of them have been completed, thatching the roundhouse and cooking shelter with turf and heather begins on April 1.

Thatching in progress

“Visitors will be able to see thatching in progress,” he explains. “We reckon it’ll take a month, maybe two, but it’ll be a brilliant way to immerse people in the experience.”

While the journey to raise the Crannog Centre from the ashes hasn’t come without stress, Rich is filled with an overriding sense of joy and exhilaration.

“There’s the obvious stress that comes with building anything – it’s a new build, and there have been over-runs,” he says.

“We’d hoped to open in autumn, but we’re 100% opening on April 1!

“It’s been a real delight watching these skilled craftspeople work, and passing their skills and knowledge on to apprentices.”

While traditional skills have been employed, Rich says that with the exception of the roundhouse, these aren’t “clinical reconstructions” of prehistoric buildings.

“They are demonstration shelters, and to tap into the agency of the craftspeople 2,500 years ago, we’ve given the agency to the craftspeople of today to do it,” he says.

“They’ve brought their own styles to it, but the skill and craftsmanship is levels above.”

Space to tell the story

And where the new centre excels – over and above the old one – is in the space it has to tell the story of craftmanship.

“What we had was great, and award-winning, in spite of the tight space,” Rich says.

“But what we have here is fantastic, and it will be improved by the space.”

Just as the original replica roundhouse burned to the ground, these new buildings won’t last forever. Rich expects he might get “eight or 10 years” out of them.

“They were never built to last,” he says. “We’re going to track how the buildings move, how they change, and that will help us tell the story better.

“For example, we’re creating different caps (the top of the thatch) on buildings. One has spagnum moss, one has rush, one has clay, one has skin and one has nothing at all.

“We’ll see how these living buildings fare over the years.”

Devastating blaze

It took Rich a while to come to terms with the devastating blaze. But, like Mike, he’s always been determined to focus on the positives.

“Crannogs would’ve collapsed or burned down thousands of years ago,” he reasons.

“There were no suspicious circumstances around the fire. It was just a terrible accident.

“So we focused on building something bigger and better.”

But what happened to the old crannog can’t be ignored, I suggest. Rich agrees.

As such, tour guides will make a point of talking to visitors about the incident – and the opportunity it afforded to forge ahead with the new centre while remembering the old site and its history.

Looking around, I notice there’s no sign of a crannog, let alone three. But that was always part of the plan – build the Iron Age village first and fret about the crannogs later.

Tour guide

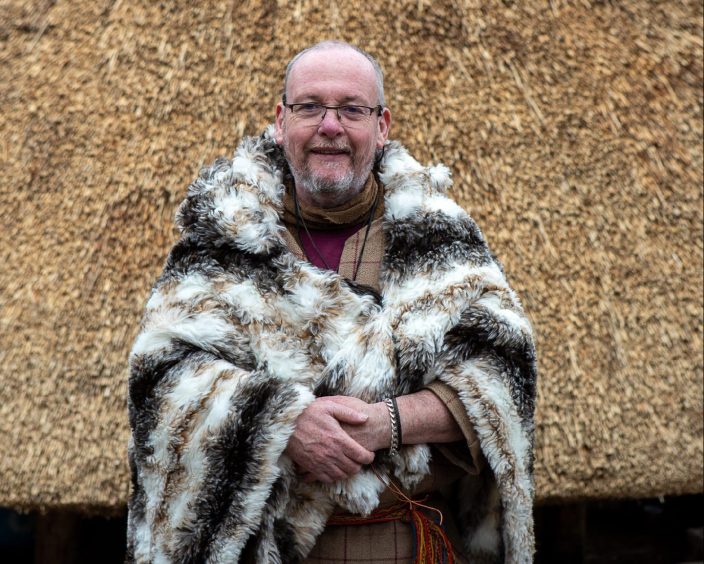

As I’m gazing out at the loch, I catch sight of John McGarry, dressed in a resplendent (fake) wolf skin.

He’s worked as a centre tour guide for 13 years.

“Because we’ve no crannog yet, I do a tour in the museum and talk about the artefacts,” says the 59-year-old.

“I put them into historical context and let the imagination run to give people an idea of what life was like in the Iron Age.

“Work starts on the new crannogs in April. We learned a lot from the first one in terms of building methods, and that’s part of the story.”

Living history

I also catch up with Cat Hotchkiss, a vernacular building craftsfellow with Historic Environment Scotland, and thatcher Brian Wilson.

Living history creator Caroline Nicolay is shimmying up a thatched roof when I pin her down for a chat.

“It’s a brand new site, so it brings in people from different worlds attracted by life in the Iron Age that don’t usually meet,” she says.

‘So much fun!’

Lara McLeod is the new marketing and events officer. She’s only been in the role a week when we meet.

“Day one, I was doing manual labour!” she says. “Day two, half manual labour, half social media, and every day since has been different. It’s been so much fun.”

When I tell Lara I was here in May last year helping to build the new Iron Age Village as a volunteer, her face lights up.

I’d not only helped to debark massive larch logs, which would be used to build the skills shelters, but I’d worked alongside archaeologist Brendan O’Neill to weave the walls of the roundhouse using coppiced hazel “rods”.

Will my “work” have been torn down because it was shoddy, I wonder?

“No, no – it’s still there!” she assures me. “Having people like yourself, the public, and volunteers, coming along to do little things, gives a sense of ownership.

“It’s all about community. There’s a much disconnect in today’s society, so to be so involved feels magic.”

Humbled by the support

I finally spot the man behind the grand project – Mike. He’s exhausted but upbeat.

“It’s been some journey!” he smiles. “We’ve been incredibly humbled by the support we’ve had, and the quality of the workmanship at the new site is breath-taking.

“A lot of love has gone into making it happen.”

Mike is keen to tell me about the mission to keep the “integrity” of the buildings, and how the “harvest zone” on Drummond Hill will allow the centre to grow its materials.

“It’s about building a legacy,” he says. “It’s not just a case of build and walk away. It’s about maintaining and expanding these skills – that’s why it’s called a ‘living museum’.”

Hotspot for wild swimmers

Before I leave the site, I deliberate, albeit briefly, going for a dip in the loch. It looks so calm and peaceful, and I’ve got lovely memories of having swum here in summer – plus, it’s a hotspot for wild swimming.

While Lara recoils at the idea – “it’s way too chilly!” – she assures me that wild swimmers are more than welcome at Dalerb.

“We’ve got hot showers and picnic benches, so there’s no need to worry about missing out on a swim!” she says.

I decide to leave it for another day, and instead simply stare out at the glassy loch and watch the ducks swim by.

- The grand opening on April 1 will see the Iron Age village brought to life with music, singing, storytelling and craft workshops.

Conversation