Scotland from the Sky, a new three-part BBC TV series presented by James Crawford, explores the country from the air. It opens up many secrets and surprises, as Gayle Ritchie discovers.

On rare days, when Loch Cluanie is at its lowest, two chimney stacks poke out of the dark, glassy waters.

Look closer and you might spot the desiccated stumps of old trees, and a road to nowhere, disappearing over a crumbling stone bridge into the loch.

This surreal, otherworldly view, which offers up relics of a by-gone era, is best understood from above.

The fascinating story of the loch’s transformation is told in Scotland from the Sky, a new BBC One Scotland series presented by James Crawford.

He believes the best way to view Scotland’s magnificent scenery – and to make connections with the past – is from the air.

In the series – an exhilarating mix of aviation adventure and historical detective work – James takes to the skies to explore the country, combining modern aerial shots with rare archive material from Scotland’s National Collection of Aerial Photography to tell the story of the making of a modern nation.

“The view from above is much more than pretty pictures,” reflects James, publisher at Historic Environment Scotland (HES).

“Aerial photographs capture the imagination in ways no other photos can. The view from above is uniquely powerful, offering the strange sensation of being at once distanced from and connected to the world below. Height – quite literally – broadens your horizons.”

During James’s travels, one of the most striking discoveries is just how much Scotland’s post-war hydro schemes – which raised water levels to build dams and create electricity – transformed the landscape and affected communities.

Comparing aerial photos taken by the RAF in 1947 of two lochs in Glen Shiel and a stretch of the original Road to the Isles between Skye and Edinburgh with modern day versions, the changes are compelling.

“They show an entirely different landscape,” says James, who grew up just outside Auchterarder.

“In the post-war period, the hydro schemes raised Loch Loyne and Loch Cluanie significantly – up to 30m – and drowned roads.

“We drove to the end of the line at Loch Loyne to watch the tarmac just disappear down into the loch. We also saw the crumbling remains of an old Telford bridge, now a bridge to nowhere.

“A 1940s RAF aerial survey of every inch of Scotland was used to identify the best sites for the hydro schemes. In the 1950s, people were told ‘this valley is going to be flooded – you have to move out’”.

Loch Cluanie of today is a mesmerisingly beautiful, yet strange, sight from above, particularly when the water is low.

Trees on the shores were cut at the base before the planned flooding so their tops wouldn’t poke up above the water. Today, during dry spells, you can spot the tangled stumps, which James describes as resembling “petrified octopi”.

But most powerfully of all, two chimney stacks emerge from the loch, rising up from the underwater home of a family forced to flit.

“A former gamekeeper who grew up in a croft beside the loch remembers playing in the house as a boy with the family who lived there, and playing shinty on the road outside it,” says James.

“He has vivid memories of driving on the road with his dad for the last time, to find it had been washed over.

“On one hand, the planned flooding was essential – it brought electricity to the Highlands – but it’s easy to forget that it caused a fundamental transformation of the landscape, which impacted upon communities.”

The series begins with James charting the dawn of aerial photography – a century ago – an era which he describes as being about “brave, barnstorming aviators risking absolutely everything for a picture.”

“The magical combination of powered flight and photography sparked a revolution,” he muses.

“In the years leading up to the First World War, the view from above was vital. Aerial photos were taken from airships which patrolled the skies, inspecting the coastal defences designed to protect Scotland’s people from German invasion.”

Flying over Belhaven and Haddington in East Lothian, James notes that WW1 defensive trenches are still visible, although some are now buried under forestry and a golf course.

“During the war itself, cameras were taken into the skies over Belgium and Frances to photograph weak points in the trenches which could then be attacked.

“Tragically, the life expectancy of these young men flying over trenches in primitive aircraft was just a week.”

In the first episode, James takes his own photographs from one of the only First World War biplanes still flying – a Bristol F.2B Fighter.

“It was incredibly difficult,” he says. “It was like taking pictures in a hurricane. There was no windshield and because of our airspeed, I was being hit by winds of more than 100mph.

“But 100 years ago, photographers had cameras the size of briefcases and used heavy glass plate negatives which they developed in the air – and they had people shooting at them.”

After the war, these same pilots and photographers set up the world’s first commercial aerial photography company, Aerofilms.

James went up in a helicopter to recreate one of their 1930s flights over Perthshire.

Looking down on his home town of Auchterarder, he is struck by the transformation.

“It’s that wonderful moment when the familiar becomes something completely different,” he says.

“Auchterarder in the 1930s had a population of 2,000, half the number of today. It was known as the Lang Toun because of its long spine. But now it’s developed middle-aged spread!

“It must be a sign I’m getting old but I remember when all of it was just fields.”

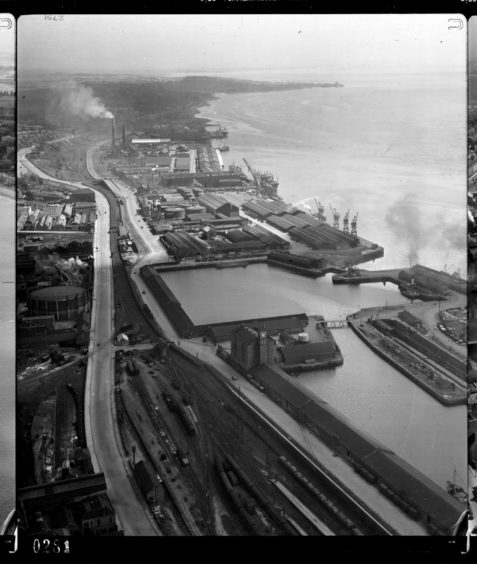

Striking changes can be seen from the air – with entire industries wiped out – as James flies over Perth, Blairgowrie and Dundee.

“In 1930s Perth, Pullar and Sons Dye Works was the largest employer in town, with 2,000 people arriving at work on trains,” he says.

“Today the factories have gone, the railways have gone and it’s now a retail park. Comparing now and then, you see a radical transformation.”

It’s a similar story in Blairgowrie, the railway station that once shipped tonnes of locally grown fruit now a supermarket and the town’s mills long gone.

In Dundee, James tracks the demise of the jute industry via 1920s and 30s aerial photography when it was a skyline of tall chimneys.

“Moving through time, those chimneys disappear,” he says.

“Today out of all Scotland’s big cities, Dundee is the one experiencing the most rapid change and you see so much of that from above.

“The harbour lay derelict for decades but now the area is undergoing a £1bn three-decade long redevelopment, a grand experiment in cityscaping that’s unparalleled in modern Scotland. And from the air, you see how the striking new V&A fits into the city like a jigsaw piece.”

James also flies over Blair Castle, and discovers how aerial photographs taken by Aerofilms in 1933 were used to boost tourism.

He looks at 1940s photos taken of nearby houses in which people are looking skyward and waving at the biplane’s pilot, such was the novelty of seeing a plane at that time.

James flew hundreds of miles in his quest to chart Scotland’s past, present and future, but a highlight was flying over the Strathearn Valley in an open cockpit 1945 Tiger Moth biplane, following in the footsteps of his hero, O.G.S. Crawford.

“He flew over the trenches in WW1 as a photographer but while he was up there, he was spotting Roman and other ancient remains.

“After the war, he became the Ordnance Survey’s first archaeology officer and in 1939, he made a pioneering flight over Scotland.

“After the Second World War, others took up the torch, but Crawford is still seen as the father figure of aerial archaeology.”

The sun was setting over the valley in late summer last year when James took to the skies in the biplane to follow a near 2,000 year old route featuring Roman forts, roads and sections of the Antonine Wall.

Ancient features emerged from the landscape below as he flew from Perth over Findo Gask, Braco and down to Falkirk – features that remain hidden at other times of the day.

“One way of spotting archaeological remains from above is to fly when the light is low at sunset or sunrise; what photographers call ‘golden hour’,” he explains.

“It’s then that you get ‘shadow sights’ – humps and bumps appear in the land that you never see any other time.

“They might be Roman camps or ancient hillforts or burial sites that could be thousands of years old.

“Because of the low-light and the time of day, these traces suddenly appear everywhere in our modern landscape, giving the sense there are ghosts around us all the time.

“You can see vividly the presence of the past in the present day.”

Another fascinating find which was revealed thanks to aerial photography was one of the oldest archaeological sites ever discovered in Scotland, at Crathes Castle in Aberdeenshire.

“A severe drought in 1976 revealed crop marks which showed up a site around 7000 years old,” says James.

“There’s one theory that it’s the world’s oldest time-keeper, a Mesolithic Neolithic lunar calendar, although it’s impossible to really know. It certainly had some ceremonial purpose.”

In James’s mind, aerial photography is like a flick book of the past.

Even today, in 2018, when most of us are used to flying, he believes there’s still something mesmeric about the view from above that no other view can compare with.

“Take to the skies at a certain time of day,” he says, “and it’s the closest you can get to time travel,” he says.

info

Scotland from the Sky, a new three-part series, starts on BBC One Scotland later this year.

Presenter James Crawford takes to the air to discover forgotten factories, abandoned villages and secret military installations.

From the first pictures taken from WW1 biplanes to modern day drones and helicopters, this is the story of how Scotland’s countryside, communities and cities transformed in 100 years.

Over the past decade, James has researched Scotland’s National Collection of Aerial Photography – an archive of millions of images held by HES – and has written a number of photographic books on its history, origins and application.

His new book, Scotland from the Sky, which accompanies the BBC series, is published on March 28.