Barry Mill, a working water-powered mill, is a rare example of Scotland’s industrial heritage. Gayle gets the lowdown from the Angus attraction’s miller

Whirring, clunking, banging and splashing – it’s all happening at Barry Mill.

In fact, when I turn up to meet the miller for a tour of the picturesque 19th century sandstone building, I can barely hear him talk.

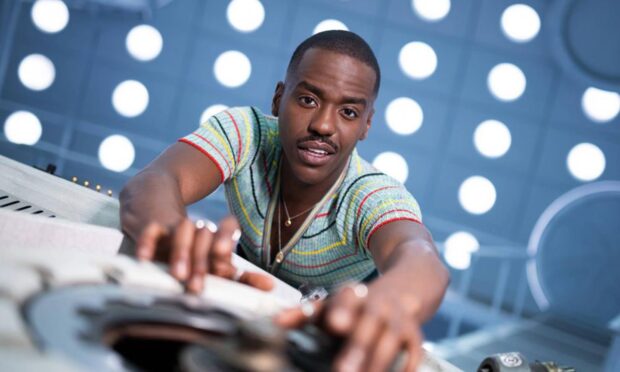

Bursting with anecdotes about the mill’s history, soft-spoken Ciaran Quigley is a man worth listening to.

“Barry has been a site for several mills since at least 1240 and was commercially operational until 1984,” he tells me.

“It was then restored, and has been operated by the National Trust for Scotland (NTS) since 1992.

“It offers a great record of rural Scottish milling practices of the pre-mass-production period, before technological changes and imported raw materials rendered many mills obsolete.”

Indeed, such a fate befell Nether Mill, a short distance downstream from Barry Mill. It was demolished in the 1960s.

As for Barry Mill, it produced animal feeds and oatmeal until 1984, when flooding damaged the lade.

It still functions, producing small amounts of meal, flour and wheat, but only for demonstration purposes.

Ciaran, a carpenter to trade, took over as miller five years ago and adores his job.

He’s full of information about the origins of phrases which derived from milling, and pops these out willy nilly.

“There’s ‘grist to the mill’, ‘the daily grind’, ‘milling around’, ‘take your turn’, ‘put through the mill’ and more,” he grins.

“People went to the mill because they needed oats, but they also went to barter; to do deals and trades.

“Many didn’t trust millers – they had a reputation for being dishonest and farmers would leave with less grain than they’d taken in!”

There was even what was called a ‘devil’s hole’ – a secret hole where a portion of a customer’s meal would “disappear”.

Three-storey Barry Mill contains a meal floor, a milling floor and a top, or “bin floor”.

Originally, oats arrived in sacks from neighbouring farms and had already been threshed – and there’s an example of a traditional threshing machine on display.

The oats were then dried in the mill’s peat-fired kiln and sent down a chute to the meal floor to be collected in sacks again.

The mill is powered by Barry Burn – there’s a working dam and lade half a mile upstream, which channel water to the mill wheel.

Ciaran allows me to tip a bag of grain into the “hopper”, trigger the waterwheel by operating a lever, and hoist up a sack – a very heavy one.

Taking me down steep steps into the basement, he shows me a series of levers, cogs and gears. His eyes light up as he explains how they control the mill’s power.

What strikes me is just how organic the mill’s mechanisms are. It’s a living animal, creaking, clanking and producing a deep, bassy hum, reminiscent of a trombone. It sure is a noisy place to be. It’s also a potentially very dangerous environment.

Robert Mackie, the miller in 1881, was killed when he fell through the pit wheel.

“He was mangled by cogs and machinery; his head would’ve been taken clean off,” says Ciaran, with a grimace.

Outside the mill, I meet a group of volunteers maintaining a footpath.

“Voluntary work varies widely – from thinning woodland and maintaining machinery to organising events,” says Ross Hughes, community outreach ranger for NTS.

“We’re always looking for volunteers and we’re flexible about how much you want to get involved.”

Anyone with an interest in history is sure to love a trip to Barry Mill, whether as a volunteer or a visitor. I highly recommend it.

info

Derelict Barry Mill was acquired by the National Trust for Scotland in 1988, and was fully restored over the next four years. It was threatened with closure in March 2009, but has remained open thanks to local support and extra funding. Ciaran plans to make the mill more interactive this summer, introducing a play area for kids and making it “more child-friendly”. There are also plans expand the cafe and shop.

See www.nts.org.uk/visit/places/barry-mill for more information.