Forming a consensus on Scottish pebble jewellery is like trying to win agreement on salt or sugar in porridge. It’s one or the other for most folk (though neither for this breakfast purist).

Set with ‘Scotch pebbles’, agates, or other semi-precious and native stones such as Cairngorm, granite, citrine and amethyst, and taking Scottish themes, such as miniature claymores, shields or clan symbols, or popular motifs such as thistles and Celtic knots, ‘Scottish’ jewellery was hugely popular in mid-to-late Victorian times. It was both affordable and fashionable and, as the railways expanded, Scotland became a prime destination not only for its beautiful scenery, but because of the fascination it held for Queen Victoria herself, who owned and wore such hand-engraved jewellery.

One women’s magazine reported in 1837: “Scotch jewellery as well as Scotch costume is de rigeur.” Another magazine in 1878 described the new look as: “A perfectly dazzling combination of silver – burnished, dead and frosted – combined with precious stones.”

As polished pebble jewellery gained in popularity, a small industry met the demand (much of it in England, particularly Birmingham), and some of the finest, precisely-cut examples were sent to the great exhibitions of the late 1800s. Most pieces were set in silver, but the best were made in gold, though invariably left unsigned.

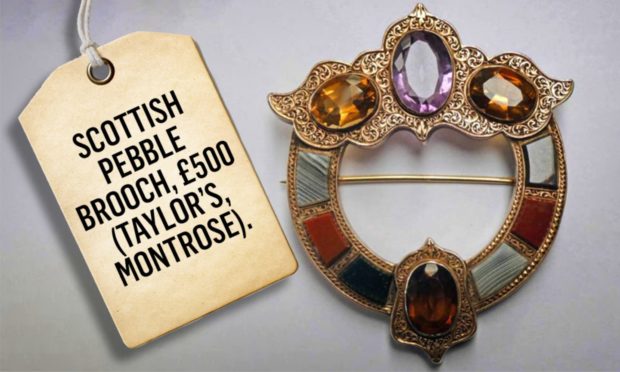

Taylor’s of Montrose auctioned a selection of this distinctive and traditionally functional jewellery on July 27, including the fine 19th century gold plaid brooch illustrated.

Just over two inches in width, the brooch was set in an engraved gold mount and beautifully composed with amethyst, citrines and agates.

It attracted an equally-handsome £500.