‘Street art’, ‘graffiti’, ‘spray painting’, even ‘vandalism’ – to the untrained eye, these are interchangeable names describing an oft-maligned art form.

Whatever you call it, it’s there, adorning Dundee’s riverside walks, illuminating underpasses, criss-crossing over the cracks and crevices of the city’s unloved corners.

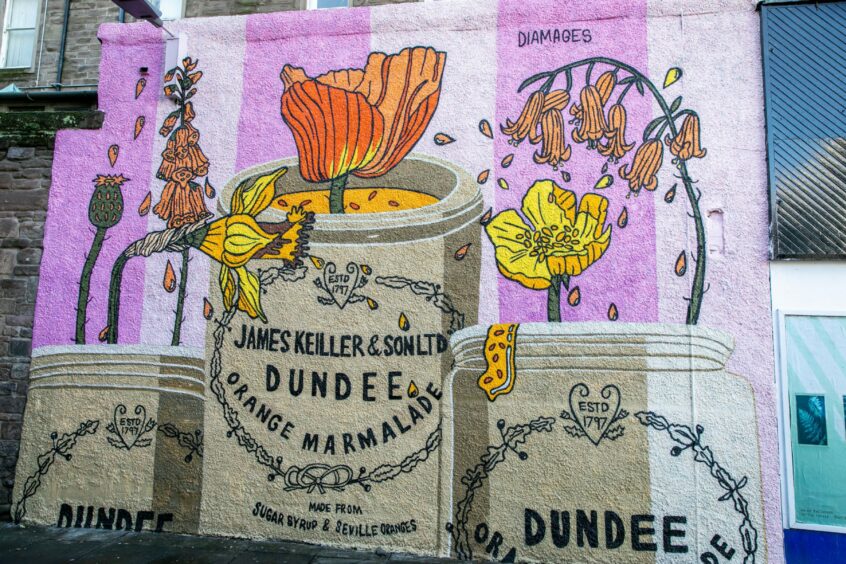

But as up-and-coming street artist and Dundee native Diane Selbie (known as Diamages) has learned, not all sprayed art is created equal.

And even in a scene which presents itself as lawless, anarchical and alternative, there are rules to be followed, and lines to coloured inside.

“There’s a constant battle between ‘street art’ and ‘graffiti’,” explain Diane, 28, whose most well-known work is the Keiller marmalade mural at the Keiller Centre.

“Graffiti is predominantly names. If you go down to any of the legal places in Dundee or any of the spaces that have been graffitied, it’s mainly tags [adopted names or logos graffiti artists use to identify themselves].”

Former Monifieth High pupil Diane bought her first spray paint cans aged 14, and admits that in her younger days “me and my friends were naughty with it”.

She started off spraying song lyrics on abandoned building in Dundee, and “dipped in” to the world of tagging as a teen.

“We thought we were hilarious,” she giggles, recalling her first forays into the sometime-legal (often not) art form.

“When it comes to art I’m really curious. So I was interested in [tagging], and in finding out who was behind all of these things and what enticed them to put their names up everywhere.

“When I was younger, I did a bit of that, but I thought it was more about ego than somebody walking past and being able to relate to it.

“So now I’ve stuck with the street art side of things. Floral designs, things that are bright and fun for people.”

‘A different world’ of kings and jokers

Much of the work Diane does is on Dundee’s legal walls – designated spots for graffiti artists and street artists to practice their designs and play with paints without breaking the law.

Her larger murals, such as the Keiller piece and her designs at the Victoria Community Garden, have been commissioned.

But part of spray painting culture is doing ‘illegal’ works – ones on walls which have not been sanctioned by the council or a private client, and which can technically be counted as vandalism.

The relatively harmless nature of Diane’s work – mainly flowers, everyday objects and family-friendly images with few words – means that for the most part, even her illegal pieces have been well-received by the public.

Moreover, with her recent exhibition in popular Westport venue Gallery 48, it’s clear her work is part of a larger cultural shift, transforming spray painting from ‘vandalism’ to a treat for the eyes, or even a public service.

“Most people try to look past the spray paint can and see what you’re actually doing. And I think most are appreciating it as a medium now,” Diane says of Dundonians’ responses when she’s out painting.

“You get a lot of older people going past saying ‘we don’t mind the art but we don’t like the hieroglyphics’, meaning the people’s names and things. So I think it depends on what they see you painting!”

In fact, she’s even had a couple of police officers find her mid-painting in an abandoned building – and tell her to keep going.

“The police turned up to check what was going on, and they actually gave me permission to finish my painting,” she giggles.

“They both added me on Instagram to follow my work! So it seems to make a difference if it’s a bit of art, rather than a name.”

However, within the community of artists, the story is very different; for Diane, it was “like a different world”.

She reveals that she received a barrage of online harassment and threats from prominent members of the city’s graffiti community, known as “kings” over her work, with some artists deliberately “dogging” (ruining) her pieces with obscenities and even “painting the poo emoji on my stuff”.

“I’m not away to say I’m anything like Banksy,” jokes Diane, “but he is predominantly street art, and graffiti artists dislike him a lot.

“Both of them might be classed as ‘graffiti’ because they’re illegal, but a lot of the people who do graffiti don’t appreciate street art being in the same place.”

There’s a strong whiff of misogyny in Diane’s all-too-familiar tale of a woman trying to break into a male-dominated space.

And perhaps space itself is the issue, with too many (literally) big names jostling for prominence on the ever-changing canvas of city walls.

“These people feel like they have an ownership of the legal spaces in Dundee, I suppose because they popped up around the time of them starting,” explains Diane.

“But the idea wasn’t just for one person to be able to paint there.”

‘It’s a huge sign of disrespect’

After downing tools while still at school, Diane picked up spray painting again about two years ago during lockdown.

And she admits that the unspoken rules of respect were something she was conscious of navigating as a newbie.

“I tried to pick my spots carefully, because you’ve got to be a little bit respectful of who you’re painting over,” she says.

“When I saw a piece that was there for a long, long time, and it had been ‘dogged’, I would then paint over that. But [the ‘kings’] don’t like somebody new going over their stuff I don’t think, it’s just seen as a huge sign of disrespect.

“I didn’t mean it like that. If you go anywhere around the world to a legal wall, you don’t really get to know how long it’s going to be up. That’s sort of the unwritten rule of a legal wall.”

Meanwhile when it comes to illegal pieces done by others, Diane’s own code is simple: don’t touch.

“If you’re ruining somebody’s work that they’ve taken a bit of a risk to do, that’s asking for problems,” she warns.

“That’s when the real disrespect comes into it. And I’ve not gone over anybody’s stuff like that, at all.”

Indeed, the risks of being caught spray painting illegally aren’t insignificant – months in prison, fines up to £5,000 and on-the-spot £50 fees are some of the measures doled out to perpetrators of such “criminal damage”.

So why do it?

Wall work is in Diane’s DNA

For Diane, the reasons are part nature, part nurture.

She grew up working in her parents’ wallpaper shop on and off, and is poised to take over the running of the business soon.

“It seems that everything I do involves walls,” she laughs.

“My parents started that company in our garage when I was tiny, and it was just nice to be around all of the art there. Lots of inspiration and seeing what people like on the eye.”

Her process – using an iPad to plan out her designs and then ‘doodling’ on the wall first to help map out details – makes it clear Diane’s inherited her parents’ eyes for large-scale design.

To her, a wall is something to be made beautiful. And she’s a tough cookie who has refused to let pushback from aggressive players quiet her.

In fact, for the past two years she’s run an annual Girl Jam, where women interested in trying out spray paint can accompany her to a legal wall and try it out for themselves.

And as Diane points out, the other driving force to spray paint is rebellion.

Street art eased agoraphobia after trauma

She reckons that for many artists in Dundee, spray painting is a way of publicly venting against the rising addiction and mental health crises facing the city; crises that many of the community members are directly affected by, including herself.

“I suffered with a bit of agoraphobia at one point after a traumatic life event that happened to me,” she says candidly.

“I didn’t really want to leave the house, and Covid… came around just at the end of all of that. It was one isolation to the next. But I really knew that I needed to get out the house and do something.”

Picking up her spray paint got Diane back into the cityscape of her hometown – and made it feel like home again.

But running deeply alongside her love for Dundee is a sense of grief and injustice about the suffering the city holds.

“It did help me connect to Dundee again, and I feel like a Dundonian,” she smiles.

“This is a place I really love. I care about the people in it. I just think there’s so much right now that is sad for people.

“My Disco packet was based on the idea that Dundee was the drug-death capital of Europe at one point. I just saw it everywhere I was going, and I was feeling so upset by it.

“There’s a lot that fuels my art, the personal stuff and also just observing what’s going on. And you can’t always put that into a photo of a flower, but it’s there.”

Ultimately, in spite of the challenges she’s faced, Diane is undeterred from pursuing her artwork; like any dedicated artist, she understands the complicated emotions that come with the territory.

“I think the reason I need a big canvas is that I’ve got a lot to express. And I think that might be where the common denominator is with us all, because they [the graffiti artists] have got a lot to express as well.

“It’s definitely clear that there’s a lot of anger.

“But if a city was happy, there would be nothing to say.”

Conversation