When it comes to the art of Zoom, the trick is to do interviews in front of a blank background if you don’t want the interviewer to glean personal information about your life.

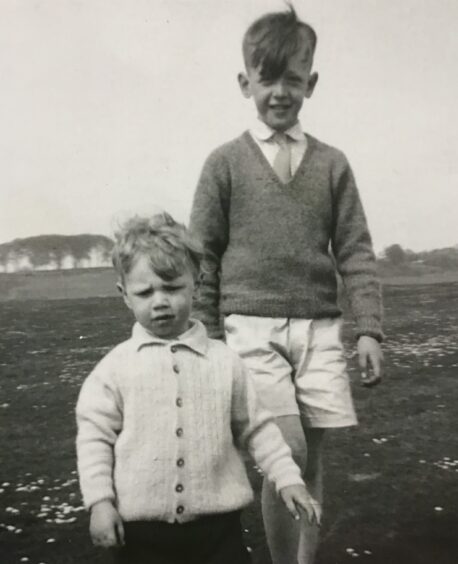

Globally renowned artist brothers David and Robert Mach of Fife do not subscribe to this notion.

As their Zoom screen kicks in for our chat, an admittedly belligerent David, who’s not finished his lunch, is on screen tucking in to a giant piece of delicious looking cake.

The last time this writer spoke to David, he was making plans to burn a semi-naked “effigy” of himself on Lower Largo beach.

It was part of an art installation by Fife-based artists Celie Byrne, Phill Jupitus and Mark Small.

David assures me that if you go down to Lower Largo beach looking for driftwood nowadays, you won’t find any.

The reason for this, he says, is that his driftwood collecting has very quickly gone from “a hobby to a f***ing obsession”.

The 67-year-old, who became a dad again last year, now can’t go for a walk on the sands without “hauling something back”.

Today though, we have convened on Zoom to talk about the Mach brothers’ first ever collaborative exhibition – Mach 2 – which is being staged to mark the 150th anniversary year of Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum, which is directed by Dundonian Caroline Mathers.

It’s a conversation that explores everything from the creation of this exhibition, to their creative influences growing up in Methil and their “bat sh*t crazy” relatives behind the then Iron Curtain in Poland.

What work can be found in David and Robert Mach’s Stirling exhibition?

David Mach, as one of the UK’s most successful and respected sculptors, is known for his dynamic and imaginative large-scale collages, sculptures and installations using diverse media.

This includes coat hangers, matches, magazines and many other materials.

The Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art and Design graduate has created a large and diverse body of artworks using regular colour-headed dressmaking pins.

His works have featured in exhibitions around the world, including London, New York and Hong Kong.

His brother Robert Mach, 61, meanwhile, has, for over 30 years, primarily worked on sculpture, installation and collage for his brother.

During that period, he has also consistently produced his own artwork, exhibiting widely in the UK and internationally.

He has concentrated increasingly on expanding his use of foil wrappings.

He utilises the brightly coloured wrappers from products such as the iconic Tunnock’s Teacake to ‘gild’ sculpture and to produce two-dimensional works.

Robert and his older brother have been in group shows together with other people.

However, this is the first time it’s been just the two of them.

Robert exhibited at the Smith a few years ago.

The one joint work for that exhibition was a giant tiger statue made from the wrappings of Tunnock’s teacakes.

Easy Tiger, which went on display at the Royal Academy of Arts in London, now lives at Stirling after the gallery bought it.

The current exhibition is a “natural extension” to one they were going to put on to support Stirling’s now unsuccessful bid to make the shortlist for the title of UK City of Culture 2025.

However, David says that having worked together on “individual things” for a long time, this first show together is also “like another opportunity for you as an artist”.

David says: “When Robert said we were going to do it, I said ‘well what am I going to show I haven’t got anything?’

“But it turns out you’ve got hundreds of little things tucked away in various corners of the studio.

“If you come in to see this show, you’ll be like ‘what the f*ck, what the f*ck, what the f*ck’! There must be about 100 pieces in here.

“But we’ve done it without really batting an eyelid.”

How did brothers David and Robert Mach get into art?

Born in 1956 in Fife, David Mach attended Dundee’s Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art where he chose to specialise in sculpture because he thought it was the most demanding, intellectually and physically.

Following a postgraduate year, he won a scholarship to attend art college in Warsaw.

However as Martial Law had been declared in Poland, he was unable to take up his place.

Instead, he was invited to do his MA at the Royal College of Art.

Lecturing at Kingston University and at the Contemporary Art Summer School, Kitakyushu, Japan during the 1980s, he was nominated for the Turner Prize in 1988 and four years later won Glasgow’s Lord Provost Prize, going on to have a distinguished career with exhibitions and in academia.

He moved back to Fife a few years ago.

David explains that he’s guilty of “jumping from one huge installation with 100 tonnes of stuff to a thing the size of a postcard”.

However, his contributions to this exhibition involve a lot of smaller work with a “hell of a lot of detail in it”.

“There’s a piece in it which has 28 separate works inside it,” he says.

“That involves me with hundreds of thousands of pins, or match heads.

“There’s quite a lot of collage, or cartoon collage.

“Picking up things like the Beezer, Dandy and Commando books and chopping them up and putting them back together again.

“There’s beautiful drawings.

“That’s also the thing you grew up with and what people know.

“They know about comics and cartoons. I like to find a language that we all use.”

How did Robert Mach get into using sweetie papers for his creations?

That sense of art connected to real life is something that also inspires Robert.

Art was not his thing originally.

He studied English and philosophy at Edinburgh University.

He then worked as a systems analyst and a garden centre manager before a spell as a househusband looking after the kids.

But even from when he started university in 1980, he was helping David build one of his sculptures, made from thick Yellow Pages.

His own work has developed since then.

The first time he created art with sweetie papers was for a show in 2009.

Their mum and dad, Martha and Josef, had a “cheap plaster figure of Jesus, Mary and Joseph” which he covered in foil wrappers – and it sold.

Thinking he was on to something, he made more of them – and it “kind of slightly took over”.

“A lot of the wrappers I use are tinned sweetie wrappers,” he says.

“A lot are found things.

“You get strips of foil off the back of a paracetamol tablet packet. It’s all over the place. It’s a fairly British thing.

“But if you are making something and you discover you need eight bits of foil, you think ‘I better buy eight of these bars’ then end up eating them all to get the extra foil!”

Robert particularly likes the foil on Marks & Spencer chocolates – so he has to eat a lot of them to get enough. He also eats a lot of Tunnock’s.

However, the company generously gave him rolls of fresh foil a few years ago to keep him going.

People also send him things like milk bottle tops, for which he’s immensely grateful.

“The important thing is these are items in your world,” says Robert.

“The world I live in is going to Home Bargains or I’ll buy things from Amazon.

“Normal things. The world of Leven High Street. It’s that kind of world.”

David adds: “The point he’s making is he didn’t go to the art materials shop and buy the stuff there.

“We got it where we f***ing live and that’s always a good thing.

“There’s always this mystification about artists. Like they come from another planet.”

Concerns about ‘cowardly’ online trolling

Conscious that he’s beginning to “rant”, David says one thing that afflicts contemporary life is that “we’ve managed to hide ourselves away from each other” through online activities and “cowardly” trolling.

That’s in stark contrast to growing up in Fife where “everyone is trying to tell you tae f**k off!”

He thinks younger people are increasingly missing the connections they got when they were young.

“Take the passion and the pathos of a f**king milk bottle top,” he says.

“Who’s actually watched a wee sparrow pecking at the top of a milk bottle – something that actually effects your whole soul?

“If you take away the things that affect your soul, you have f**k all, and we are all going to be scrabbling around in the mud again!”

Apart from leaving “cold hard cash in their sweaty mitts”, the artists want people to be “excited, happy and thrilled” when they visit the Stirling exhibition.

The art world can be “too serious” and they are proud they’ve made some of it “quite funny”.

But if anyone asks where their inspiration comes from, David will say: “I’m already inspired!”

How did family influence David and Robert Mach growing up?

“We are not from an arty family but we are all very artistic,” he says, thinking back to their upbringing in industrial Methil.

“Our dad was a miner, my mum a housewife.

“They were very extravagant nutty people who looked ordinary from the outside but they were f**king nuts!

“We were never encouraged to do anything.

“There was sort of an understood thing that you’ve got to make your own way. Nobody ever said it.

“It wasn’t like we were forced to play the piano or take painting lessons. None of that.

“Whatever artistry happened to us it was lurking in there.

“I didn’t know I wanted to be a real artist until I’d been to art college for four years.”

Childhood trips to Poland

Robert explains how as kids, they’d go to Poland to visit their dad’s family – after escaping Soviet Gulags, he served as a member of the Fife-based 1st Polish Parachute Brigade during the war – and to Glasgow to visit their mum’s side.

It always felt like they were “doing something that was kind of different”.

David agrees, stating that they always felt “a bit more exotic than everyone else”.

“It’s odd isn’t it,” he reflects.

“Because when we went to Poland it was behind the Iron Curtain. It was a big adventure. It took two days to get there.

“The people who were there were batty. They were bat sh*t crazy.

“Our entire family – concentration camps, Gulags in Siberia, they’d fought on the Russian front with the German Army.

“Uncle Karl sitting there chain smoking with a chunk of his nose missing where it had been shot off.

“Everyone was hugely extravagant, but completely inspiring.

“They all drank like crazy, they all smoked.

“The women would all be swooning to the accordion.

“Our dad was a man who’d been chained to the back of a f***ing tractor and hauled into Siberia in whiteouts telling you that you were lucky to be chained to the back of that tractor.

“We’re like, ‘come on how can you be lucky to be chained to the back of that tractor’?

“He’s like ‘if you’d stepped away from that long line of prisoners being dragged at the beginning of the Second World War, you were dead.

“Whiteout in Siberia? You wouldn’t last 10 seconds’.

“So we had two perspectives.

“Our mother was incredibly negative about everything.

“Our father was ludicrously positive about the most difficult things.

“And there’s us sitting in the middle of that.

“We weren’t trying to make sense of it. We were probably just sitting listening.

“By hook or by crook, I think we were inspired to be creative – although nobody actually said it.

“You would never hear the word creative in our house!”

The Mach 2 exhibition runs at The Stirling Smith Art Gallery & Museum until April 7.

Conversation