This is the first part of an exclusive four-part Courier serialisation of the first biography on Dundee’s famous son Michael Marra, by celebrated Scottish writer James Robertson.

Michael and I spent a lot of hours sitting on either side of the kitchen table, talking. He could make a cup of black coffee last a very long time. I wish now I could remember all the things he told me across that table. I can’t, but I do remember a lot.

During the summer of 2016, I worked my way through a box of photographs, theatre programmes, scrapbooks and other miscellanea amassed by his wife Peggy, as I tried to find a way into telling Michael’s story. I had been trying for a while. To begin at the beginning and follow a chronological line from there might have been the obvious route but it didn’t seem to fit with the kind of man he was. ‘Obvious’ isn’t the first word that comes to mind to describe Michael. Clear, coherent, audible, unmistakable, distinctive – all of those, yes. But Michael Marra, obvious? I don’t think so.

So I began to wonder how he would do it. Where would he start, if it was down to him to make sense of that accumulation of memories? Possibly by saying it was not a project that interested him, that he had better, more important things to do with his time than tell his own story. Then I might reply, ‘But it’s not your time, Michael, it’s mine.’ And he would stop and consider that. Thinking of it as somebody else’s project, he would want to make some observations, even offer some help. Because he was that kind of man: considering, considerate, thoughtful, observant, helpful. He would want the thing to work, for the other person.

I was also, for reasons largely beyond my control, way behind schedule. Michael would have understood. Running late? He could easily have advised slowing down, or even stopping and going back a few stages. He had a good appreciation of effort and attention to detail. He understood that some jobs take more time than you thought was available. ‘The apple will fall when the tree is ready,’ he said once, when asked when the next album was coming out.

He always wanted to get things right. More than once he told me, ‘If it’s easy, it’s probably not worth doing.’ Which is a sentence containing reassurance and discouragement in equal measure: the sort of formula Dundonians pride themselves on. And Michael, to the marrow, was a Dundonian.

The writer and journalist Neal Ascherson likes to quote the following dark joke: ‘I hit bottom. But then I heard somebody tapping underneath.’ Ascherson declares this to be a Polish saying, but I can’t help thinking how Dundee it is. Maybe it was exported a few centuries ago, when the Scots were migrating to Poland in great numbers, as soldiers, merchants and craftsmen; when Cochrane, MacLean and Weir became Czochranek, Makalienski and Wajer. And maybe, like a homing pigeon, the joke found its way back again.

-

For more from the series, click here

Michael said in an interview, ‘For any artist, Dundee is just the perfect place to look at the rest of the world. Charles Mingus had a book called Beneath the Underdog. I always thought they should put that under Dundee on the sign outside the city.’

I remembered how he came to write the song ‘Muggie Sha’’. It was inspired by photographs from a book circulated by the Dundee police round the city’s pubs in Edwardian times. Michael had got hold of copies of some of the pages of this book. On each page were two photographs, one facing the camera, one in profile, of an individual barred from all of Dundee’s pubs. These were folk who were down on their luck. They were troubled and troublesome people, and in terms of social strata they were some distance below the meanest underdog.

And Michael admired them, especially the women, and he admired their achievement in earning themselves a city-wide drinking ban. I could hear his voice, ‘I wanted to celebrate these magnificent women.’ Which he did. From their point of view. And what did he have them say? ‘Eh’m no as bad as Muggie Sha’.’ Who but you, Michael, could have homed in on that place of intense, black-humoured empathy?

So already I found I was talking to him and he was talking to me, and not for the first time since he left us. When he was alive, the prelude to such a conversation would be a phone-call. ‘Hello. James?’ The unmistakable gravel of his voice. ‘It’s Michael.’ As if it could be anybody else. ‘Are you working?’ (He expected you to be.) ‘Do you have time for a chat? Good. I’ll come round.’ By the time I’d made the coffee, round he would have come. And we would go from there.

Who was Michael Marra?

Michael Marra (1952-2012) is widely recognised as one of Scotland’s most innovative and original songwriters. The range of his work is extraordinary, from the miraculously redemptive (Frida Kahlo’s Visit to the Taybridge Bar) through the angrily political (I am Shirley McKie) to the heartbreakingly poignant (Happed in Mist), warmly celebratory (Niel Gow’s Apprentice) and hilariously funny (Baps and Paste). He wrote hundreds of songs, and many are now regarded as classics which will outlast the products of passing trends and fashions.

Dundee was in his bones and much of his output reflects the dry wit and subversive viewpoint of the city he once described as ‘a rich, dark, healthy place for art and artists and a beautifully lit vantage point from which to look at the world’. Having dipped his toe in London’s music industry in the late 1970s and early 1980s, he realised that he preferred to have complete control of his own time and his own work, and came home. Subsequently he asserted his unique take on life, articulated through his instantly recognisable voice – ‘gravel stirred in melted chocolate’ as one description has it.

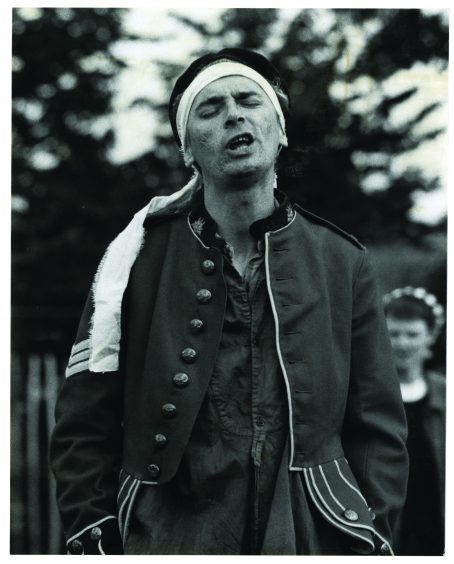

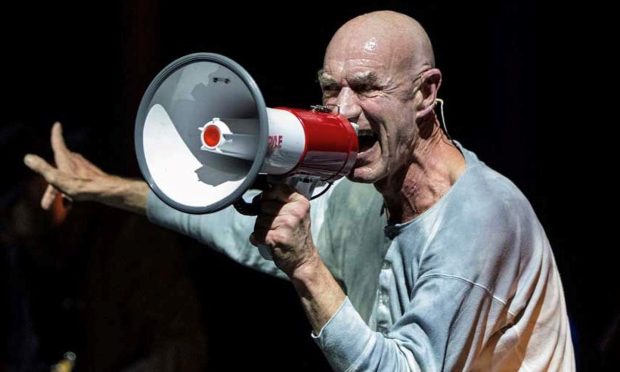

Michael also had a career in theatre, creating words and music for countless shows, acting and directing, and writing his own plays and an operetta. He produced other musicians’ records, worked in television and film, was an accomplished visual artist, wrote short fiction, and collaborated with many different performers over the years. He was a great football enthusiast, too, and many of his songs have football themes.

His songs have been covered by many distinguished artists and his contribution to the culture of his hometown and of Scotland was acknowledged by honorary doctorates from Dundee and Glasgow Caledonian Universities, as well as by other awards both in his lifetime and posthumously. Five years after his death he is still much missed and much loved. Michael Marra: Arrest This Moment is the first full-length biography of a man who continues to exert a strong and positive presence across many areas of Scottish culture.

The author and Michael Marra

James Robertson knew Michael Marra’s music long before he met the man himself, but when he and his wife Marianne (who had known Michael and Peggy back in the 1970s and 1980s) settled in Newtyle in 2003, they found themselves just a few hundred yards from the Marra home. Over the next nine years Michael would often come round to chat about music, books, art, politics and life in general.

When, a year or two after Michael’s death, the idea of a book about him was suggested, James and Michael’s family discussed what form it might take. They agreed that such an unconventional man deserved something other than a ‘straight’ biography. It was while pondering how to go about the task that James thought of reconstructing the long conversations he and Michael had had across the kitchen table, and turning them into, as it were, posthumous interviews.

These ‘kitchen conversations’ are interspersed between the more factual chapters about Michael’s upbringing, songwriting, musical and theatre careers, collaborative work and his other interests including football. James’s hope is that these dialogues supplement the biographical facts and help to capture something of Michael’s personality, including his sense of humour.

Michael Marra. Arrest This Moment is published by Big Sky Books and is available from October 20 via all the usual stockists or direct from www.bigsky.scot. £16.99 for paperback, £24.99 for hardback.