The third in an exclusive four-part Courier serialisation of renowned Scottish writer James Robertson’s biography.

Among the numerous projects to which Michael was committed in the late 1990s was another major theatre production: he wrote the songs for, and acted in, Chris Rattray’s The Mill Lavvies. This hugely popular play was first performed at Dundee Rep in 1998, was revived in 2002 and again in 2012, just a month before Michael’s death.

Set in the early 1960s in a Dundee mill where most of the workforce are women, the action takes place in the mill’s male toilets and dips into the lives of five men whose banter, tricks, petty cruelties and occasional kindnesses to one another reflect the changes going on in society around them.

There is a particularly Dundonian underdog take on life in the scenarios and dialogue of the play. Michael’s songs are beautifully crafted to tap into this theme, and it is not doing an injustice to the strength of Rattray’s writing to say that they are the highlights of the play, partly because they slot so seamlessly into the narrative, enhancing and never disrupting it.

-

For more from the series, click here

Some of these songs, which teeter on the edge of pathos but never quite topple in, are rightly regarded as top-drawer Michael Marra creations, Big Wide World Beyond the Seedlies, Broom Crazy and Gin Eh was a Gaffer for to Be among them. Oh Meh Goad, in which Erchie, the janny, is urged by his workmates to supply them with ever more surreal non-rhyming limericks, is a comic masterpiece.

Perhaps the most memorable song, though, is If Dundee was Africa, a geography lesson in sound-pictures. At one point in the play, Erchie wants to know where North Africa is but, since he is unable to read or write, one of the other men has to find a way of explaining its location to him without the aid of an atlas or globe. He does so with this song:

If Dundee was Africa,

And Fife was Antarctica,

If Arbroath was India,

And Perth was Peru,

In that darkest of continents

How happy Eh’d be,

Cause that would mean Aiberdeen

Was deep in the Mediterranean Sea,

And a’body would agree

That’s a no bad place for Aiberdeen to be.

As well as songwriting and musicianship, Michael wrote short stories and plays, acted, drew and painted, took photographs, manipulated the images he made, made collages, constructed objects, whittled sticks and invented things. Conversation, too, was a form of art for him. He enjoyed the company of visual artists and engaging with their ideas: he liked hanging out in their studios, and he counted Vince Rattray, Andy Hall, James (Jimmy) Howie, Francis Boag, Calum Colvin, Eddie Summerton and many more as friends.

It was obvious to Michael’s friend Andy Pelc (a.k.a. ‘Saint Andrew’) that:

“Michael was basically a rebel when it came to art or anything else. He was the rebel of the family. He was into art but almost anti-art in any formal or academic context. Anything that involved classical, formal training, he would reject that. I have it in my head that Michael might have applied to go to art school. But if he did apply, if he had been offered a place, I don’t think he would have accepted it, or he wouldn’t have stayed. He would have hated being told how to go about “doing” art.

“In the same way, if you wanted Michael to, say, watch something on television, the worst thing you could do was tell him,’Watch this programme, you’ll really like it.’ That immediately erected a barrier. He would take umbrage at you telling him what he should watch or would like.”

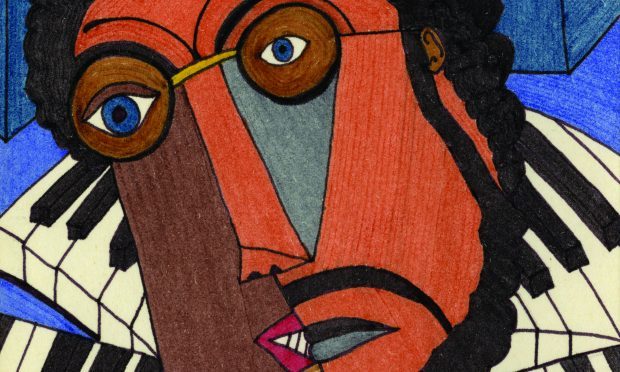

Back during the days of touring with Skeets Boliver and Barbara Dickson, Michael had found that a lot of hours were spent sitting around waiting for things to happen. To help himself relax before gigs, he bought himself crayons and felt-tip pens and started drawing – often very detailed, multi-lined images that needed a lot of concentration and a fair bit of colouring-in.

The influence of modern masters like De Chirico, Matisse and Picasso is evident in his drawings and paintings, but his unique perspective meant that there was something identifiably Marra-like in nearly all of his output, which included a large number of cartoons and drawings enhanced by captions, speech-bubbles or other text.

There was also always a sense that he wanted to break down boundaries between different art forms. He noted that wherever painters are working – whether they are artists or painters and decorators – there is usually music too, coming out of a wee radio or a big blaster. Music, as he put it on Candy Philosophy, is “the sound of painters painting paint”. So why wouldn’t visual art have a powerful presence in a music studio?

Hermless: Michael’s Scottish national anthem

In the introduction to Hermless, Michael said:

“This song was my suggestion for the national anthem of Scotland, and it’s one of my songs, and that would appear to be a very impertinent thing to do, especially in Dundee as, you know, we take a pride in our modesty.

But, I must stress, at the time there were only two suggestions, and I didn’t like either of them really. Both of them were kind of military, or based on hatred of our neighbours, and I find that unacceptable, although we’re not alone in that, because I did a study of national anthemry the world over, and we are not alone, you know generally they are pretty duff.

I think the South African one is beautiful, it’s celebratory and it’s up and you can tell it’s full of love, so I like that one. The Dutch one has a great tune. But apart from that they’re all pretty dodgy, I think. They’re either based on extravagant claims about themselves, or just plain simple hatred of their neighbours. In fact if you ever get a chance to read the Algerian national anthem, have a drink before you do.

Anyway, this one is very simple. The chorus goes ‘Hermless, hermless, there’s never nae bather fae me/ I ging to the lehbry, I tak oot a book, and then I go hame for ma tea.’ Okay? Take great care over the word ‘lehbry’, it has a Latin root but it is definitely Dundee, that one.”

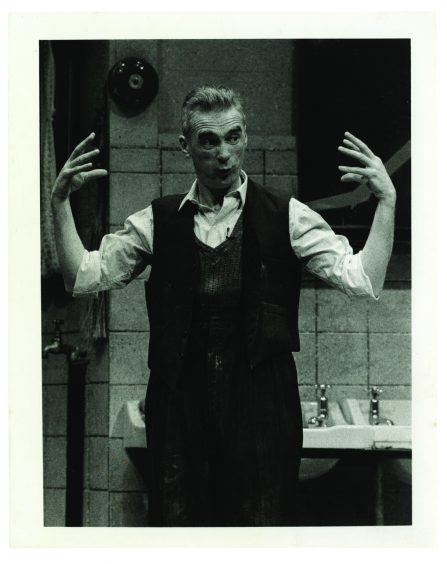

Michael the actor

If Michael had not been primarily a songwriter and musician, he could easily have had a full-time career as an actor. Theatre directors for whose shows he wrote music and songs were often quick to spot his talent for adopting a persona with complete conviction.

One review of the show A Wee Home From Home, in which Michael appeared with his friend the dancer Frank McConnell, commented: ‘By standing still and doing, apparently, nothing, he created a dark violence which completely dominated the stage. Few actors have that gift.’

Michael’s acting ability was related to the way he prepared for music gigs. He was notoriously nervous before a gig – ‘stage fright to the power of ten’ was how he described it – but once he was at the piano and singing he was ‘in character’ and his anxiety was invisible to the audience. Similarly, he always maintained that his songs were not personal, not about him, even if they contained the word ‘I’.

“Performance is an act,” he used to say. “You’re like an actor, and that’s what an actor has to do: become someone else.’ He also likened it to being “on a tightrope all the time you’re out there. You have to be the tightrope walker.”

Michael Marra. Arrest This Moment is published by Big Sky Books and is available from October 20 via all the usual stockists or direct from www.bigsky.scot. £16.99 for paperback, £24.99 for hardback.