The final instalment in an exclusive Courier serialisation of celebrated writer James Robertson’s biography on the Bard of Dundee.

Playing football mattered hugely to Michael and his brothers, as Nicky Marra recalled:

“Just underneath the line of plane trees on Harefield Road there was a flat area which we developed into a football pitch, in other words eventually there was no grass left on it.

“There were always other boys looking for a game. That could be a bit risky if you didn’t know them, but you had a wee bit of security playing with your brothers. We’d also go up to the hat factory in the industrial estate behind Clement Park where there was a huge area of flat grass. You’d go up there with a bottle of water and be there all afternoon, just playing football for hours.”

Nicky continued, ‘There was a football renaissance going on in the city in the early 1960s. Bob Shankly was appointed manager of Dundee in 1959, and then Dundee won the league in the 1961-62 season.

“In our summer holidays we would walk down to Dens Park from Lochee and see the players coming out at the end of training and ask for autographs, the likes of Gordon Smith and Alan Gilzean. Gilzean was a huge hero. Michael’s later description was ‘he strode like a colossus over the Tullybaccart’ because Gilzean was a Coupar Angus man.

-

For more from the series, click here

“Michael was a Dundee fan whereas I became a United supporter. Mum would take us to games – if it was Dens Park one time it would be Tannadice the next, or to see the Harp, the junior team. I can’t exaggerate how important football was for us.”

The beautiful game was something that would remain beautiful for Michael throughout his life. He could see through the ugly things that accreted to it – the obscene amounts of money, the occasional outbreaks of violence on or off the park, the sectarianism of the Old Firm, the commercial exploitation of the game through merchandising and selling television rights – none of these could take away his pleasure in football at its simplest, the moments of grace and magic, the way it can be, at its best, an international language of shared humanity.

For him, additionally, as an artist, it provided endless material for songs and for reflecting on wider matters.

Michael himself was a good player as a teenager, Nicky recalled:

“He was what they would call a tasty winger, but he did not like physical contact. So he would play on the wing and when we got older, into our twenties, we played in a team called the Thomson Street Academicals. This was moving up a gear into amateur, Sunday morning football, and Michael didn’t like that because it was hard, physical, and he developed bad knees. I’m not sure if that was for real or an injury of convenience.”

Michael was a Dundee fan from the age of 10 when they won the Scottish League in 1962. In the European Cup campaign that followed, Dundee started off by beating FC Cologne 8-1 at home. It was the first game Michael had seen under floodlights and he had never experienced excitement like it.

In later life he was also a keen follower of Celtic. He resisted the tribalism of the game and found incomprehensible its appropriation by bigots and fanatics in other parts of the country. For Michael, football was always bigger than any one team.

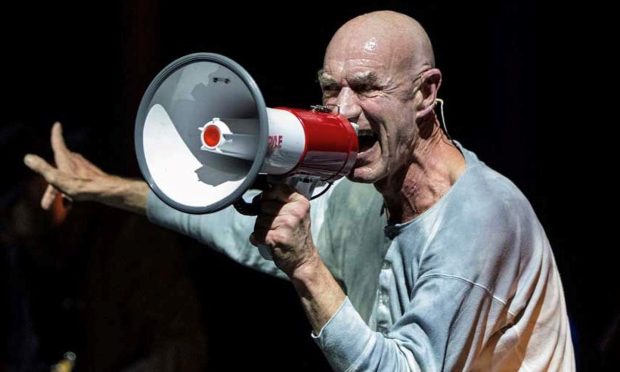

Perhaps his most sublime song about football is Reynard in Paradise. It manages to connect the city to the countryside, football to freedom, the beauty of a fox to the beauty of men, and it even carries an echo of Burns’s Song: Composed in Augus ( Westlin Winds with its condemnation of blood sports. This is how Michael would introduce it at gigs:

“I was listening to the radio one Saturday afternoon, and it was a football match taking place in Glasgow between Aberdeen and Celtic. And during the course of the commentary the commentator said, ‘An amazing thing has just happened, a beautiful and healthy fox has just run on the park.’

“Why would such a wise creature would put himself in such a precarious position. It just didn’t seem to be the right place for a fox to appear, but there he was. So I began to wonder where he’d come from.

“Maybe a member of his family had been killed by the hunt, and he had moved into sophisticated Glasgow, tired of the rural way of life. Something like that. But anyway, no matter what reason, I wrote this song, and during the course of the song, the fox revises his opinion of mankind, having watched Aberdeen play Celtic.”

Thus a true story became a fable in Michael’s hands. “Men can be graceful / This much I know”, the fox says, but he speaks in Michael’s voice.

Michael in Turin – and Grace Kelly at Tannadice

When Michael was invited to perform in Turin in 2000, he prepared for the trip by asking Frankie Robatti, a neighbour in Newtyle, to translate the introductions to his songs into Italian. Michael learned them by heart and delivered them like a native speaker to a very appreciative audience. Between songs he told them of the time he had met the great AC Milan and Italy player Gianni Rivera in the Nethergate in Dundee, in May 1963 when Michael was eleven. They shook hands. AC Milan were at Dens Park for the second leg of the European Cup semi-final. Their players looked like film stars, while the Dundee players were all peely-wally. As Michael was speaking a man in the front row stood up, turned round and began to count back through the years on his fingers. When he signalled his satisfaction that Michael’s claim was correct, the entire audience roared its approval.

One of Michael’s much-loved football songs is Hamish. This is how he used to explain its origins before singing it at gigs:

“A great footballer called Ralph Milne asked me to write something to celebrate the testimonial year of his team-mate, the great Dundee United goalkeeper and entertainer Hamish MacAlpine.

“I admired Hamish although I was a Dundee supporter but we are not Glaswegian about these things, and then one night I attended a match at Tannadice Park, which is where Dundee United play. The newsreader Peter Sissons pronounces it “Tanna- dee-chy”, isn’t that cool?

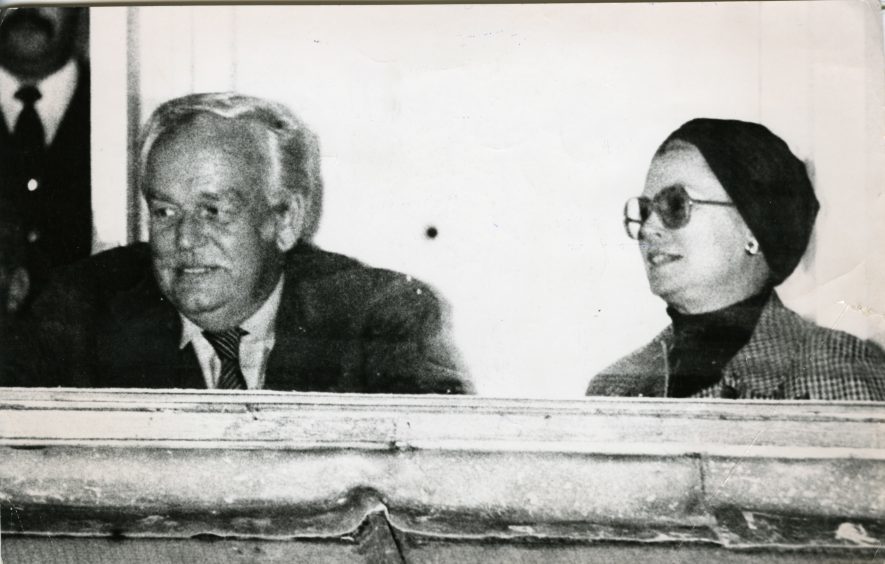

“Anyway, Dundee United were playing against F.C. Monaco, and present among us, the people of Dundee, in the grandstand, was the wonderful Hollywood star Grace Kelly. She was there with her man, I can never remember his name.

“Anyway, she was wearing a white turban – which is unusual in Dundee – but unfortunately she was sitting behind an advertising hoarding which proclaimed ‘TAYLOR BROTHERS COAL’. It was what we cry incongruous.

I had no camera so I went home and made this song. It’s called either ‘Hamish’ or ‘Grace Kelly’s Visit to Tanna-dee-chy’.”

Football in context

In his song Reynard in Paradise, Michael describes a game of football as ‘a working model of the one big thing’ – a metaphor for life in other words, or for some of its better aspects at least: co-operation, skill, passion, excitement and grace.

He was also very conscious that football, like music, had the power to demolish barriers of language, race and cultural differences.

In his song Flight of the Heron, about Gil Heron, the first black professional footballer to play in Scotland. Heron had a season with Celtic in 1951-52 and was known as the Black Arrow because of his speed on the ball.

The chorus of Michael’s song is

Higher, raise the bar higher

He made his way across the sea

So that all men could brothers be

This was part of Michael’s wider philosophy. After his death in 2012, the journalist Lesley Riddoch summed him up in these words:

“Like Robert Burns, Michael was driven by compassion, humanitarianism and a deep-seated fury at cruelty – whether that was the callous cruelty of war or the cruelty of men towards women.

“All of his work was characterised by humanity and – despite the mess humanity has made of the planet – optimism.”

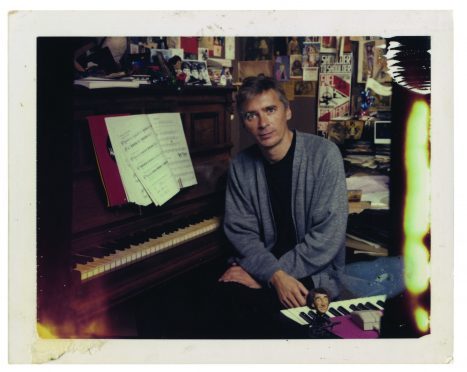

Michael Marra. Arrest This Moment is published by Big Sky Books and is available from October 20 via all the usual stockists or direct from www.bigsky.scot. £16.99 for paperback, £24.99 for hardback.