The story of the Bell Rock lighthouse – a miracle of engineering – is almost the stuff of legends. Caroline Lindsay discovers the very real story behind this famous tower.

The Bell Rock – the very name is enough to strike fear into the bravest mariner. Yet when historian Michael Strachan was first asked to write a book about the legendary Bell Rock lighthouse, his first answer was “absolutely not”.

“I felt there were enough books about the Bell and I failed to see what another book could achieve,” Michael explains.

He was finally persuaded by a colleague who would bombard him with facts about the Bell in a bid to convince him of the iconic tower’s superior status among lighthouses.

Once he’d decided to write the book, Michael realised there was a chance to do something different by producing a biography – a fuller history of events – of Robert Stevenson’s most famous lighthouse.

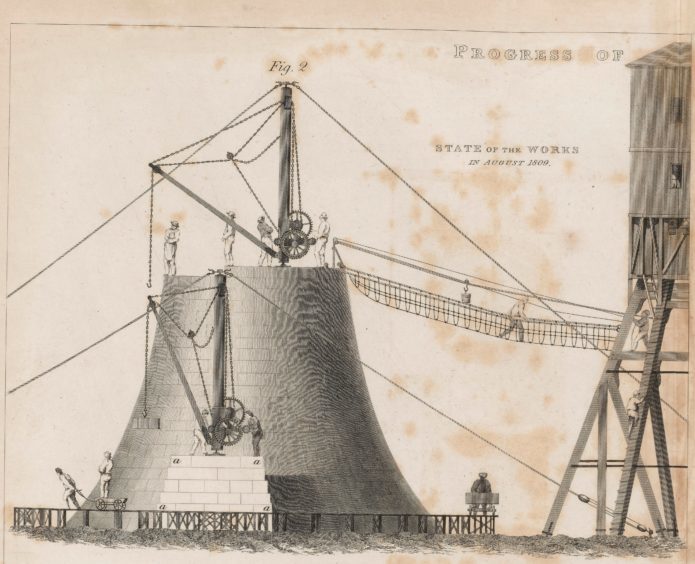

“Authors, starting with Stevenson himself in 1824, focus solely on the building of the Bell Rock between 1807-11,” Michael reflects.

“In my view this is a great shame as the tower has more of a history than those four years alone – it’s more than just Stevenson and his chief engineer John Rennie.

“The light has now operated for more than 200 years and has undergone many significant and ingenious upgrades and changes, some of them even being undertaken by non-Stevenson engineers. It was a manned light for 177 years, the lives of those keepers on their temporary Alcatraz being a source of equal fascination,” he continues.

Michael’s own fascination with lighthouses was sparked when he became a tour guide at the Museum of Scottish Lighthouses in Fraserburgh.

“I started with absolutely no knowledge of lighthouses whatsoever,” he admits. But with two degrees in history he took to lighthouse history like a duck to water and his knowledge quickly grew. Now the collections manager at the museum he is now a fully-fledged pharologist – someone who scientifically studies lighthouses.

The notorious Bell Rock is built almost 12 miles off the coast of Arbroath on the deadly Inchcape Reef, the scene of violent storms and crashing waves and which has claimed countless vessels and lives.

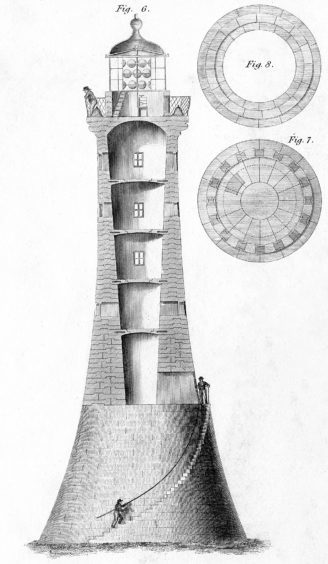

“The thing that made it so special was that it was built on a submerged reef: at high tide the reef is 12ft underwater, and barely visible above water at low tide,” Michael explains. Standing 115 ft tall, its light is visible from 35 miles inland.

Rennie suggested that the base of the lighthouse should be wider and therefore more stable and, says Michael, it’s still fiercely debated today as to which of the two men is due to credit for building and designing the Bell Rock.

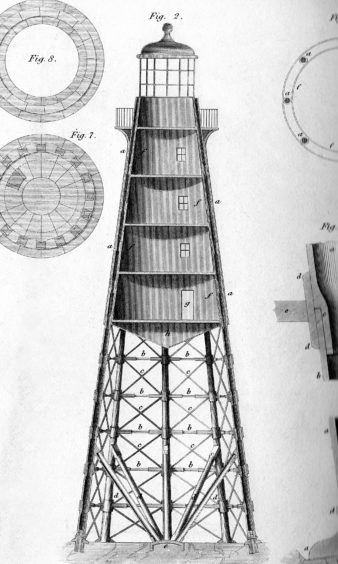

The first task was to build a beacon house on tall wooden struts, so some of the workers would have a place to stay on the reef.

“The transport of the stones from Arbroath made one unlikely celebrity in a workhorse called Bassey, who carried every one of the Bell Rock’s 2,835 cut blocks of stone from the work-yard to Arbroath Harbour for shipping,” says Michael. Commuting that short distance daily for three seasons, Bassey moved just over 2,083 tons of stone. Her skeleton can be seen at the Bell Pettigrew Museum in St Andrews.

The lighthouse was manned until 1988 when the last principal keeper, John Boath, retired. For the majority of that time there was a compliment of four keepers: three men serving on the rock, while the fourth took his leave at the shore station – the Signal Tower – at Arbroath. Each man would spend a six-week period at the station, before spending his two-week leave at the Signal Tower – if the weather permitted. The Pharos lighthouse ship would attempt to enact a landing at the station every two weeks to change keepers, as well as land food and other supplies, including oil and water.

“While the keepers kept their nightly vigils, life at the station was punctuated by the occasional visits of the engineer and by world events,” says Michael.

“The lighthouse underwent its first major upgrade in 1902 when the entire top of the lighthouse was replaced. It then had to adapt for two world wars, before safety concerns led to a complete overhaul of the station in 1963/64,” he continues. “This modernisation would see the light operate on electric, with no mains electric being run from the shore: a challenge being all the more difficult due to the little space available.”

The final punctuation came in 1988, when the station turned automatic and the last men were withdrawn.

“Automation, by its nature, is perhaps unfairly viewed in a negative light,” Michael muses. “Yes, it led to the end of the age of the lightkeeper but the innovations involved in keeping an unmanned light working 12 miles offshore are just as ingenious as the building of the tower.

“The story of Scottish lighthouses is a fascinating one. Despite the fact they have all been built on the authority of the Northern Lighthouse Board, and most of them were built by members of the same family, they all have their unique histories and identities.

“Many people have this idea that lighthouses were built and then nothing changed. In reality what happened behind the walls of those towers was constant improvement with the introduction of innovative new technologies being serviced by countless, successive keepers.”

So why are writers so fascinated by the Bell Rock?

“There is little doubt that building a solid stone tower on a submerged reef, some 12 miles off the coast at the beginning of the 19th Century was a massive engineering achievement,” says Michael. “It was the impossible lighthouse, now recognised as one of the seven wonders of the industrial world.”

Author and conservation officer Tom Nancollas is also beguiled by the Bell Rock. Describing himself as an architectural storyteller, his new book Seashaken Houses (the title is inspired by a line from Dylan Thomas), is a study of lighthouses across the UK and includes a chapter on the infamous Angus lighthouse.

“No book on lighthouses could omit the legendary Bell,” says Tom. “The stories of its gestation, operation and automation are uncommonly rich and vivid.

“But it has a significance larger than itself. For me, it is a symbol of Scotland at the peak of its powers – perspicacious, rational, urbane, mercurial – and those qualities are to be found in the lighthouse itself. More than any other tower it expresses the ambassadorial and protective roles lighthouses have in a nation’s story.”

Tom’s own love of lighthouses was sparked during his childhood.

“I grew up in some pretty marginal places and spent lots of time on coastlines in sight of them,” he explains. “They are among the rarest and strangest kinds of historic buildings and I developed an insatiable passion for them.

“In 2017 I went with a good friend and the amazing staff of the Signal Tower Museum in Arbroath – the museum is a must-visit and tells the Bell’s story brilliantly. We journeyed out on a boat – interior access wasn’t possible – on a crisp March morning,” he recalls wistfully.

“To see this tower presiding over the North Sea was humbling. It has a presence I will never forget.”

Tom reveals a little known fact about the lighthouse.

“It once housed the only Georgian library ever built in the North Sea, in the uppermost room of the tower, which had exquisite cabinetry, ornamentation and a domed ceiling,” he says. “Famous poets of the day would visit and sign the visitors’ book. Sadly, this remarkable interior was lost in a later refurbishment scheme.”

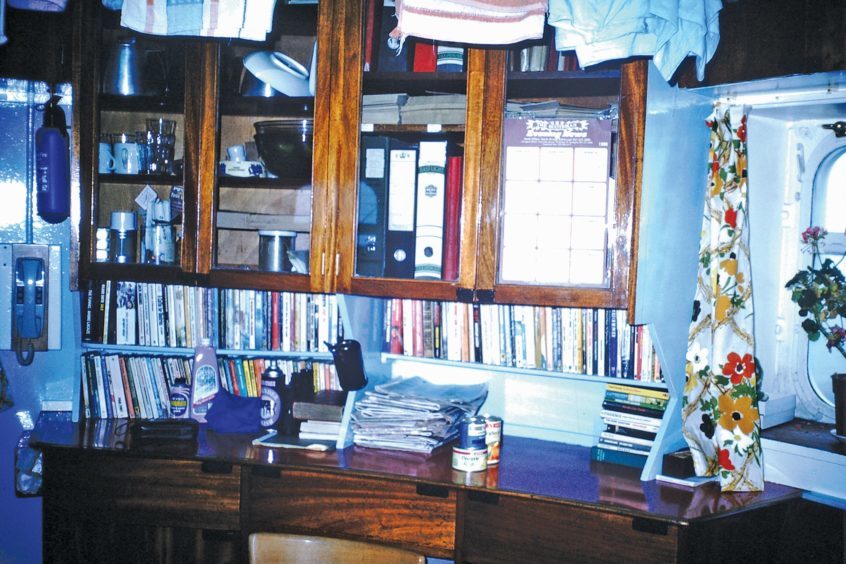

Books were something of a necessity for John Boath, the last principal lighthouse keeper on the Bell Rock, as he was posted there for three or four weeks at a time.

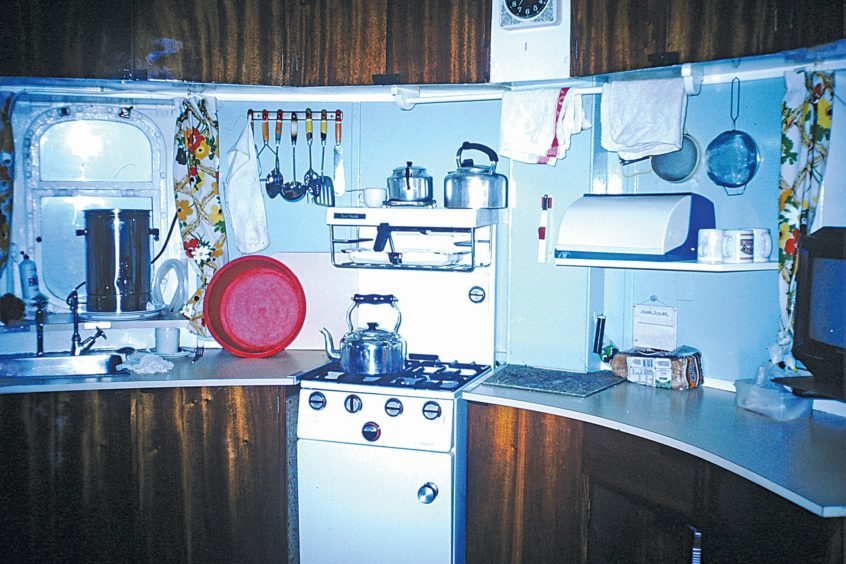

Now in his 80s, John admits it was the last posting any keeper wanted during their service. “It was like living on a vertical submarine and very basic inside as there was heating and no shower,” he recalls. “The toilet flushed with sea water pumped up to the header tank and at one stage the system broke.

“I had a single-bar electric fire to keep me warm and any power was used for navigation light, beacons, VHF and radio signals.”

Living on the lighthouse never caused him any qualms, even on the stormiest of nights. “It was quite cosy when I was tucked up in bed — it had stood there for nearly 200 years so I wasn’t worried it was going to fall apart,” he laughs.

“Bell Rock was the first lighthouse to have a TV but I didn’t watch it much. I used to read a lot and I was always in the workshop painting or making wee models and toys for my boys. I missed the family but I tended to close my mind to it.”

And if he was on the lighthouse at Christmas he made sure he marked the occasion. “Once I was away for four Christmases on the trot but I put up a tree, and I was sent a cake and the usual festive cheer in the form of bottles – although I made sure I rationed them!” he laughs.

Switching off Bell Rock in 1988 was a moving moment for John. “I was sorry to leave but I have my memories.”

Bell Rock Lighthouse: An Illustrated History by Michael AW Strachan is published by Amberley, £14.99

Seashaken House: A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet by Tom Nancollas is published by Particular Books, £16.99