I brought you a book last week – and here is another. This is a basket case of a bible, though, if you’ll pardon the phrase.

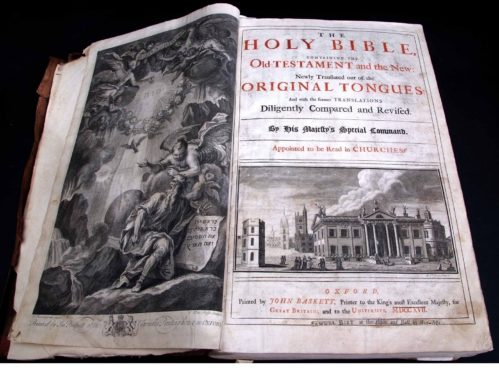

Printed in Oxford in 1717, it is John Baskett’s so-called Vinegar Bible, which also earned the nickname ‘A Baskett-ful of errors’ due to its alarming catalogue of mistakes.

Baskett, printer to the King and the University of Oxford, printed bibles from 1812, but it is his two-volume Old and New Testaments of 1717 which is known as ‘The Vinegar Bible,’ from an error in the headline of St Luke, Chapter XX, which reads ’The parable of the vinegar,’ instead of ‘The parable of the vineyard.’

It is so carelessly printed that it was at once named ‘A Baskett-full of errors,’ which is believed to be the original source of the term ‘basket case’ meaning something that is full of eccentric errors and faults.

Yet, the 1717 edition is also a landmark in English graphic art, celebrated both for the beauty of its typographical design as much as it is for its textual carelessness, and this saved Baskett from further ridicule.

Baskett, who had gained a reputation for unscrupulously buying up competing bible printing businesses and absorbing them into his own, claimed the exclusive right to print and sell bibles in Scotland – which landed him in more hot water.

In 1715 he launched a lawsuit against Henry Parson, an Edinburgh stationer who was selling bibles printed by John Watson, the king’s printer for Scotland, who claimed the right, under the new Act of Union, of printing and selling his bibles anywhere in the new unified kingdom. The litigation was eventually settled by a judgment of Lord Mansfield in favour of Baskett.

A ‘magnificent’ copy of the 302-year-old Vinegar Bible appeared at Keys of Aylsham, near Norwich, on April 11 – a volume with an engraved frontis representing Moses writing the first words of Genesis, along with 66 engraved headpieces and tailpieces.

It took £780 in the room.

As it happens, a corrected 1726 version of Baskett’s work appeared at Irish auctioneers Fonsie Mealy on April 16. Here, it was knocked down for a more modest £220.

If only my notorious mistooks would raise the value of my literary outpourings!