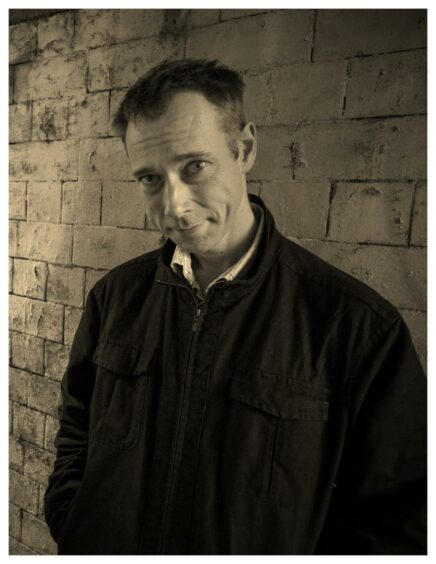

From his home in Cupar multi-instrumentalist Fraser Fifield steps out into the musical world.

He might be going to the other side of the country, as was the case recently when he joined his long-time musical partner, guitarist Graeme Stephen to film a video on the “whisky island” of Islay.

Or his travels might equally take Fifield to the other side of the planet, to Mumbai or Buenos Aires or to Eastern Europe, all of which have been locations for recordings and concerts with leading local musicians.

If you’d told Fifield, when he began learning to play the bagpipes as a schoolboy with his local GP in Aboyne, Aberdeenshire that this would open doors to working with musicians including the Indian percussion master Zakir Hussain, he’d likely have responded with an “aye, right” in the soft Doric accent that remains unchanged.

Over the years, however, Fifield has added various saxophones, clarinet, the Bulgarian kaval (or end-blown flute), and the low whistle to the bagpipes.

His expressive playing on the low whistle has proved particularly attractive to bands including Capercaillie, the Afro Celts and the mighty Grit Orchestra.

The latter was formed to interpret the music of maverick musical alchemist, another piper-multi-instrumentalist, Martyn Bennett.

Ancient and mysterious

In lockdown last year, Fifield revisited the music that his GP, Jack Taylor, who just happened to be the champion piper and long-time chairman of the Piobaireachd Society, taught him.

Piobaireachd literally means pipe music but is now used to describe the classical music of the Highland bagpipe, what the 45-year-old Fifield calls “that ancient, slightly mysterious music.”

The result of his return to his roots is Piobaireachd/Pipe Music, a startling new album that features centuries-old tunes and new compositions by Fifield, seasoned by touches learned and developed in his travels.

‘It never leaves you…’

“Piping never leaves you,” he says. “It’s kind of a blessing and a curse.

“You develop a way of hearing things totally through the bagpipe filter so that your training on the pipes informs everything.

“It’s the bedrock of everything I do and there’s a certain dexterity in the fingering that you can apply to the whistle especially.

“I’ve sometimes found myself teaching whistle workshops, wanting to tell students to go away and learn to play the pipes first. But you can’t say that to someone who’s only come to a class for an hour or two.”

During his enforced stay at home, Fifield explored and re-imagined ancient tunes, including The Flame of Wrath for Squinting Patrick, from the 17th Century, and The Lament for the Old Sword.

On the album, the former, which commemorates an act of terrible retribution, features soprano saxophone, clarinet and whistle embellishing the bagpipe melody.

The latter tune finds Fifield’s whistle, alto and soprano saxophone vividly reinterpreting its traditional variations.

Musical responses to life

He didn’t set out to make an album but the more he experimented with the older pipe tunes, the more he realised he was creating a repertoire that had a certain flow.

There were also musical responses to events such as the death of Fifield’s friend, bagpipe maker and fellow fearless cross-cultural experimenter, Nigel Richard, at the beginning of this year that chimed with the stories behind the old tunes.

“I wouldn’t want people to get the impression that the album is all doom and gloom,” he says.

An eclectic mix of sound

“It’s actually quite lively and has multi-instrumental choruses that were designed to be uplifting. There’s also a real soulfulness in the old music that I wanted to convey.

“The tune for Nigel, Being in Time, puts Border pipes together with saxophones, whistles and kaval in a bustling, slightly roguish way that he, I think, would have appreciated.”

Transferring the musical arrangements on the album to the stage might be a challenge.

A mix of performer and composer

But Fifield wasn’t thinking of the recording-to-promotion steps that have sometimes been part of the plan with his previous seven albums.

“It was more about exploring a theory I have that improvisation is simply inherent to the human musical experience,” he says.

“I also believe that improvisation once played a greater part in the music we now call piobaireachd.

“That might be impossible to prove today but it makes sense to me and I’m happiest when creating afresh – that interesting mix of being performer and composer at the same time.”