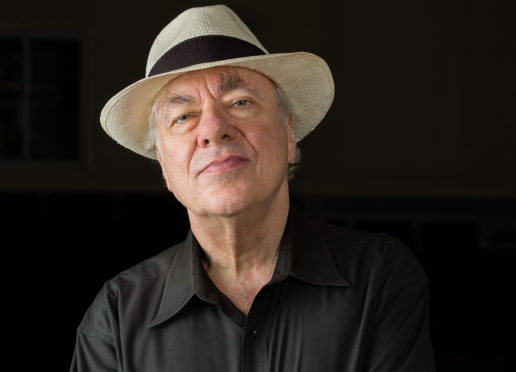

It started with a “B” and ended with a “C” but a whole alphabet of superlatives could be attributed to the performance of pianist Richard Goode at his recital in the Perth Concert hall on Sunday. Excellent, intuitive, inspired, masterful. All these perfectly fit the bill.

The “B” was Bach, the “C” Chopin but with three other Bs in the programme – Berg, Beethoven and Byrd – it meant he spanned nearly 400 years of composition. Versatility is the by-word for performers nowadays, but this was something special. The Byrd was a surprise package, a Pavane and Galliard, and it gave the concert some novelty. Seldom do you hear a keyboard work from the polyphonic era on the concert platform.

The Bach was, to continue the alliterative theme, brilliant. His Preludes and Fugues need a precision, a delicacy, a flowing technique and a restrained flair. They also need a pianist of Goode’s ability to forget their original harpsichord delivery and show that they could easily have been written for a modern-day piano.

After the Bach, Goode threw what might have been a musical googly into the works, but what was in fact a triumph. Alan Berg can be both abrasive and atonal – and hard to admire – but his piano sonata is delightfully lyrical, powerful in parts and a perfect foil to Bach’s counterpoint and fugal dexterity.

It was Beethoven’s turn next, his A major Op 101 sonata. For once, this great man came runner-up to the other composers on show, and this was nothing to do with Goode’s performance. It’s not the best of Beethoven’s 32 sonatas, but the scherzo and trio and the finale, the latter of which is full of Beethovian humour and whimsicality, are certainly its saving graces.

Then there’s the “C”. The second half of the programme was devoted to Chopin, with two Nocturnes, four Mazurkas, one Ballade and one Barcarolle. This certainly was a great eight and while there can be some pomp to Chopin’s works, there is also tons of grace, heaps of lyricism and many touches of tenderness.

Goode might be in his 70s, but this concert was a prime indication that you really can’t beat an old master.