Cathy and Heathcliff, Tom and Shiv, Sting and whoever he was singing about in The Police’s 1982 hit Every Breath You Take…

For generations, pop culture has been selling the toxic love story, and 2023 is no different.

But just two years after Dundee was deemed the worst city in Scotland for domestic violence rates, the city’s youth aren’t buying it anymore.

Oor Fierce Girls is a young women-led collective of local secondary school pupils who are determined to set the record straight about healthy relationships for their generation.

Bursting pop culture’s toxic bubble

“In the media, we often see TV shows that glamourize unhealthy relationships, using power dynamics and stuff,” explains Oor Fierce Girls founding member, 18-year-old Ashley Henderson.

“For example in [popular American drama] Pretty Little Liars, there’s a relationship between a teacher and a child,” she continues.

“And in [Netflix smash-hit] You, people seem to think the main character, Joe is attractive, but really he’s a terrifying stalker.

“But young people romanticise that and seem to want that in their lives. It’s almost as if through this exposure, we’re getting more awareness of unhealthy dynamics, but in the wrong way.”

Ashley’s fellow Fierce Girl Tamsyn points out that it’s not just TV and film that’s guilty; young adult fiction often eroticises abusive behaviour, so much so that there are entire social media trends where young people enthuse over the so-called ‘enemies to lovers trope’.

@lindahamiltonwriter Like they’re real, actual enemies. Also please enjoy my strange facial expressions of excitement. #booktok #books #bookrec #bookrecs #bookrecommendations #enemiestolovers #yafantasy #fantasybooks #bookish #bookworm #booklover #reader #readersoftiktok #reading

“There are so many books that are solely based on unhealthy relationships being this amazing thing to be in,” says the 17-year-old Morgan Academy pupil. “It’s scary.”

On their own, these pop culture trends may not signal anything for parents, carers and professionals to worry about.

Many may assume young people are discerning enough to know the difference between passion and violence, fiction and reality.

Even Ashley herself admits that “this stuff is basic knowledge”.

“But,” she adds, “not everybody has it. And so it’s easy to say ‘you should know this’, but if you never get taught, how would you know?”

Shocking peer sexual abuse statistics

Indeed, Scotland’s lack of formal education about relational abuse – particularly peer-to-peer sexual abuse – was one of the driving factors of Oor Fierce Girls’ inception.

In 2018, Childline reported delivering over 3,000 counselling sessions following peer sexual abuse in the previous year.

Romantic partners (35%), friends (31%) and other young people (34%) were all reported perpetrators of the abuse.

But crucially, the report highlighted the lack of understanding that young people have about what constitutes peer sexual abuse, with chilling Childline message board questions including: “Is this sexual abuse?”, “Sexual abuse or my fault?”, “Was this rape?”, and “I don’t know if I was raped or not?”

In the same year, a report from The Young Women’s Movement (formerly YWCA) revealed that 70% of students and 48% of teaching staff who responded to a questionnaire found that their current curriculum did not adequately prepare students to discuss intimacy with a partner.

And for young women like Ashley, Tamsyn and their friends, the fundamental lack of teaching about consent, peer sexual abuse and domestic violence has had very real consequences.

“Personally, there’s a lot of things that could’ve been avoided had I had certain education,” reflects Ashley.

“A lot of behaviours that I hadn’t realised were controlling or potentially unsafe.”

That’s why Ashley was moved to get involved with Oor Fierce Girls in the first place.

‘It seems like we should know everything’

At 16, she was a founding member of the original group of Dundee girls who volunteered through their schools to develop the Oor Fierce Girls programme in conjunction with The Young Women’s Movement, NSPCC Scotland and Dundee City Council.

Now a university student in Glasgow, Ashley is working with the new cohort of Fierce Girls to help bring education about peer sexual abuse and toxic relationships directly into school buildings across her home city.

“It’s a problem I’ve seen in a lot of people my age, not understanding healthy relationships,” says Ashley candidly.

“They got themselves into bad situations and I didn’t know how to help them, and it kind of scared me.

“So when I saw this opportunity come up, it meant a lot to me.”

Hearing a young person speak so openly about feeling uncertain is refreshing, but also jarring, in a culture which increasingly assumes teenagers are growing up faster and faster.

Could it be that adults have forgotten that teenagers are still figuring out everything we’ve already learned the hard way?

“It sometimes seems like we should know everything,” admits Ashley. Laughing, she adds: “To be fair, every teenager thinks they already know everything!

“But we don’t.

“And when you think everyone around you knows everything, then to not know what you should be doing is scary. So people pretend to themselves that they do know – and that can be dangerous.”

Digital landscape allows for hidden abuse

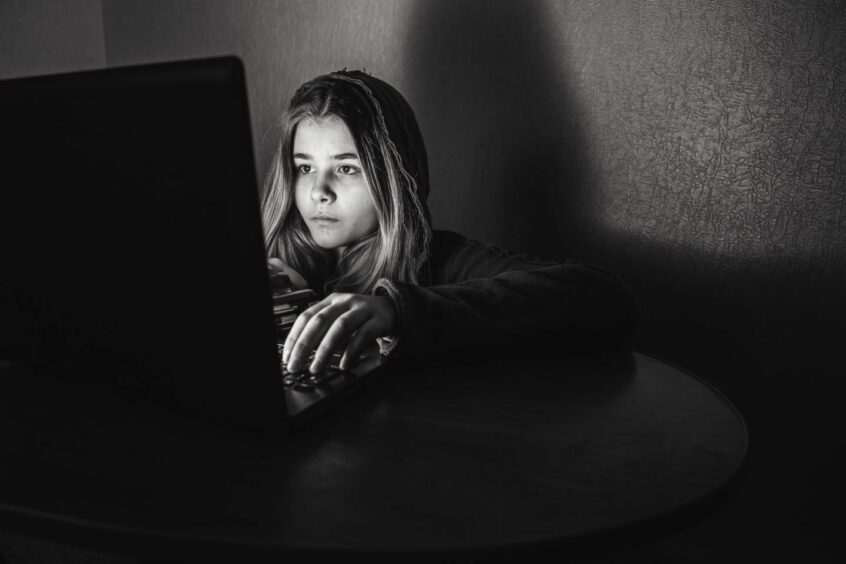

One of the more insidious facets of modern relational abuse, Ashley and Tamsyn point out, is how much takes place behind the password-encrypted ‘closed doors’ of a phone screen.

Instead of playing out in physical space where they can be overheard by friends or intercepted by chaperoning parents or school staff, arguments, threats and even sexual extortion can take place in the private digital landscape.

“There’s a lot of my friends who, I love them to pieces, but I couldn’t tell you what their intimate relationships are like,” she admits.

“And the digital age makes that divide more apparent. You can hide so much more, and still feel like you’re sharing everything.”

Navigating the ‘real’ world as a teenager is hard enough, but for young people growing up today, the digital sphere is just as big a part of reality as the physical.

With services like Childline, the digital world has already implemented readily-accessible ‘safe spaces’ for those who are worried about abuse.

But it is often anonymous, and according to the 2018 Young Women’s Movement report, 90% of pupils felt they would benefit from having a designated safe space in school too.

With that in mind, Ashley and her teammates have crafted a short film which outlines how to create a ‘safe space’ in schools; a physical room where pupils can go to seek support or advice about relationship and, specifically, peer sexual abuse.

‘Safe space’ isn’t just a buzzword

“[Speaking about intimate relationships] is obviously such a difficult conversation to have, so to have it in an open area obviously isn’t the best,” observes fellow Fierce Girl and Morgan Academy pupil Tamsyn, 17.

“So to have a space that’s more confidential and comfortable, where you feel safe speaking about whatever it is you’re going through, is quite a big thing.”

The ideal safe space, Tamsyn explains, is “a room that’s quite airy, but not big” with “a lot of natural light, bright cheerful colours, and comfortable furniture”.

And the short film emphasises that it should be attended by trained members of staff who can advise and support pupils struggling with peer abuse.

For Tamsyn, the Fierce Girls have granted a new perspective on relationships which is a world away from the culture she grew up with in South Africa.

There, she explains, unhealthy relationships are “quite normalised” so many young women like her are growing up with a warped perspective of how they should expect to be treated.

“In South Africa it’s not really focused on, mental health and specifically relationships,” she admits.

“So to be involved in something that is so big on changing that and raising awareness of it is a good thing.”

Film went down a storm at DCA premiere

The Oor Fierce Girls film was premiered at the DCA last month in an event attended guidance teachers and support staff from city schools, parents, and representatives from the partner organisations.

And the young women are already taking the campaign into schools, with several of the teachers in attendance saying they had been to workshops in school led by the Fierce Girls.

Morgan Academy guidance teacher Andrew Wallace is one of the staff members who has taken on the training. He said: “There’s more staff awareness of the need for safe spaces now.

“And we’re making young people more aware of consent. It’s important to embed it properly, not just tick a box.”

For many schools, the ‘safe space’ will be a room that already exists within the institution’s infrastructure; it simply needs a bit of organising.

Morgan’s health and wellbeing worker Justine Porter started making plans to transform her office into a safe space just minutes after watching the film.

“The animation got me thinking about how I’ve got a wellbeing room, so that’s the perfect place to start,” she noted.

“It all means more coming from the young people themselves. I’m feeling inspired to get my room ready to go.”

The city council’s executive director of children and families services, Audrey May, was also in attendance, and praised the efforts of the young women.

“You give young people their voice and you suddenly get some real, sensible answers coming back,” she said in response to the film’s suggestions.

“And some are solutions that adults just can’t see.”

Safe people make spaces safe

Indeed, the most important aspect of the safe space, according to the Fierce Girls, is that the adult manning it is a ‘safe person’.

A safe person, Tamsyn explains, is someone who is “non-judgemental, comforting and understanding” and “actually actively listening”.

Moreover, Ashley adds, the need to “take themselves out of the situation and listen to the young person”.

“Let them say how they feel and what they need, and just hear them, instead of pushing what you have been taught,” she insists.

And ‘safe people’ don’t belong just in designated ‘safe spaces’ – they can actually make a space safe, whether that’s a parent at home or a staff member at school.

But being a safe person is a full-time job, and as Justine points out, it isn’t just about how an adult interacts directly with young people; it’s about how they act around them too.

Making derogatory or discriminatory comments about others, such as characters on television or neighbours, can hugely impact how ‘safe’ you are to a child, she explains.

“The way you talk about other people in the community and on TV is what kids absorb and remember,” she says.

“Try to be non-judgemental, and show that, in order to be a safe person.”

For more information or to access the Oor Fierce Girls toolkits, visit the Young Women’s Movement website or social media pages.

Conversation