After seeing Anthony Baxter take on Donald Trump, renowned Angus landscape artist James Morrison wrote the filmmaker a letter.

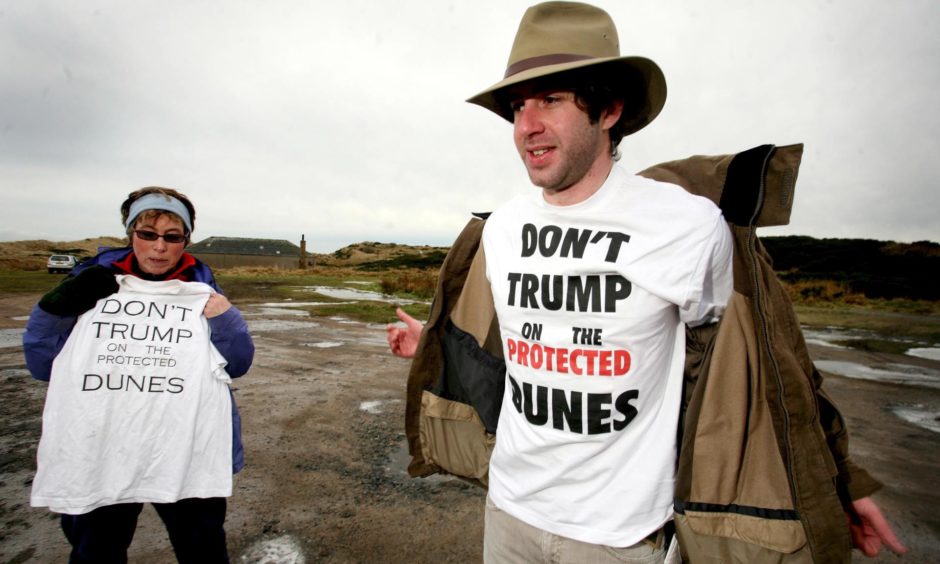

The late painter had watched Anthony’s breakthrough work You’ve Been Trumped, about tycoon Donald Trump building a controversial golf development in Aberdeenshire.

What followed was the creation of Eye of the Storm, a poignant portrait of James’s final years as he battled through ill health and failing eyesight to continue painting.

You may have heard of a Turner sky. Well, in Montrose, there is such a thing as a Morrison sky. Since 1965, the renowned landscape painter called the Angus town home.

He could regularly be seen working outside in all weathers, attempting to capture the beautiful, ever-changing countryside, skies and coastline with his paintbrushes.

Born in Glasgow in 1932, he moved to Montrose from the Aberdeenshire village of Catterline because his wife Dorothy was taking up the post of head of history at Montrose Academy.

His works feature in the collections of the British royal family and author JK Rowling, but he shied away from the limelight, much preferring to paint. He once said of his vocation: “It’s for me. It’s my argument with myself”.

Montrose-based filmmaker Anthony Baxter, 51, has lived in the town for 16 years. It was where his late mother grew up. She passed away when he was in his early 20s.

He filmed James for two years as he fought to continue doing what he loved. Sadly, James died in August 2020, aged 88, meaning Anthony never had the chance to share the finished version of Eye of the Storm with him.

Anthony still lives in the same house he remortgaged more than a decade ago to fund his 2011 documentary You’ve Been Trumped. This was a searing account of future US President Donald Trump’s golf development at the Menie Estate in Balmedie, and the residents who fought against it.

Anthony runs Montrose Pictures, an award-winning film and television production company. He has directed a number of documentaries including: You’ve Been Trumped Too (2016), A Dangerous Game (2014) and Flint (2020) a harrowing examination of the drinking-water public health crisis in the city of Flint, Michigan.

Anthony explains: “I think after 10 years of attempting to try to get to the truth in controversial subjects and holding people to account, it was refreshing to spend that time with James – and a real privilege, too.

“It came about by chance,” he goes on. “James wrote to me after seeing You’ve Been Trumped and he was really quite moved by the destruction of the landscape in Aberdeenshire by Trump’s bulldozers.

“As a painter who spent his life devoted to capturing the landscape, that seemed like a real vandalism.

“My uncle, Denis Rice – who you see in the film – was a friend of his and suggested we go out for a coffee.

“At that stage, Jim had stopped painting for a while because of his deteriorating eyesight. I think he was finding it incredibly frustrating that feeling of not being able to achieve what he wanted to technically.

“Denis had been encouraging him to get back to the painting, saying that it may be different in approach, but nonetheless poignant and important.”

Anthony asked James if he could film him, should he ever return to his easel. And so it transpired that James invited him into his studio – the door of which carries official-looking lettering on the glass that states: “WET PAINT”.

“He was very relaxed having me there,” Anthony reflects. “It was a good opportunity for me to put on record some of these moments.”

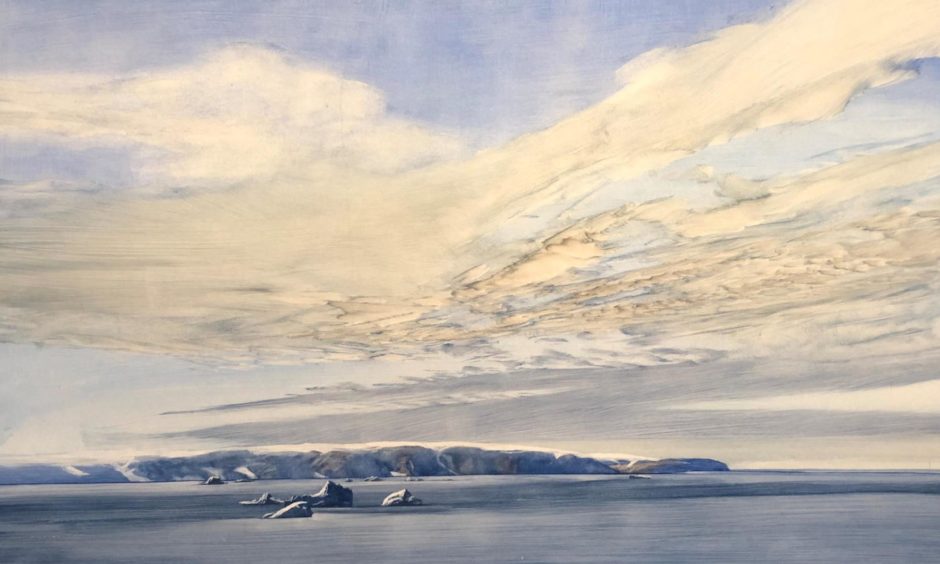

Anthony sought an outlet for the documentary and BBC Scotland commissioned an hour-long feature. Additional funding then made it possible for the film to stretch to just under 90 minutes, incorporating information about James’s painting trips to the Arctic.

Scottish animator Catriona Black came on board to bring a new dimension to James’s paintings and his memories – including a tense encounter with a polar bear while on a trip to Greenland.

Eye of the Storm brings together Anthony’s interviews with archival footage and beautiful animation against a backdrop of nature’s atmospheric sounds and songs by Scots musician Karine Polwart.

It premiered at the Glasgow Film Festival on February 28 and has been selected for other major international film festivals. It was theatrically released in the UK earlier this month and can be streamed via selected cinemas and arts organisations.

The original hour-long version will be broadcast on BBC Scotland in the spring, with the longer theatrical version being shown at a later date.

It joins James, then aged 85, as he prepares to create work for his 25th exhibition with the Scottish Gallery in Edinburgh. He had a special relationship with the gallery, showing and selling pieces there for over 60 years.

But he has been told by his GP that he cannot paint outside and his eyesight is failing to the point that he is registered as partially-sighted. James is “terrified” at the thought of no longer being able to create acceptable artworks.

The film is also interspersed with quotes, many from famous artists. Some, like James, struggled to continue creating in later life. French artist Henri Matisse famously painted with a long cane while bedridden, and Impressionist Claude Monet continued to make stunning works while suffering from terrible cataracts.

One quote from Monet reads: “I will paint almost blind, as Beethoven composed completely deaf.”

Softly spoken and seemingly introspective, James admits to Anthony that he is very self-critical. Anthony agrees he was something of a perfectionist.

“He was a lovely man. There are some artists who quite like the limelight or like to have the spotlight on them and talk about their work – he definitely wasn’t one of those,” he says.

“He was the kind of person who, on the opening of one of his exhibitions, he really didn’t enjoy that aspect of it. He was much more at home with his brushes painting outside.”

At points during the film, James can be seen watching old footage of himself, reflecting on it after all these years.

“He wasn’t a stranger to the camera himself,” says Anthony. “He had presented these old programmes for BBC Scotland called Scope.”

In Montrose, James found a subject matter that would inspire him for the rest of his artistic career. He took up a teaching post at Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art in Dundee, doing this for 22 “happy years”.

“I think that by moving to Montrose he was able to make his mark on a different landscape, which he did in an incredible way,” Anthony says.

James studied at Glasgow School of Art between 1950 and 1954 and quickly realised his style was set to differ from that of his contemporaries. His first “landscapes” were the city’s old tenements, many of which would go on to be demolished.

As well as his Scottish landscapes, James took extended painting trips to destinations such as Africa, France and Canada, including three trips to the Arctic in the 1990s.

He is also seen reflecting on a painting hanging at home called A Lady Remembered (2006). Created after the death of his beloved Dorothy, he tells Anthony: “It’s not a landscape; it’s just a portrait of grief.”

Anthony was able to film James attending his final exhibition at the Scottish Gallery in January 2020 – From Angus to the Arctic – just before the pandemic struck. In a wheelchair, his family by his side, he chatted, shook hands and learned that one of his 2019 studio paintings had sold.

“It’s sad I was never able to share the film with James,” Anthony says. “I shared it with John, his son, and Judith, his daughter, at the end of last year and they’ve been very supportive of it.”

After filming finished, James went to live in a care home and Anthony was able to visit him before Covid hit. He was still able to do some painting there.

Anthony hopes that some day in the future, Eye of the Storm can have its moment on cinema screens: “I think there will be something really magical about being able to see James’s paintings on a big screen, because nobody has ever seen that. I think they will be really powerful.

“There is something about the way we have done the sound design is for cinema so it’s a shame not to be able share it in that way.”

An audio-described version of the film has also been created. Anthony explains: “James was somebody who painted outside and he was very aware of all the sounds and atmosphere of being out in the open in the countryside. He was absorbing all of that in his work.

“We have tried with the sounds and the music and this audio descriptive version to give people who are struggling with vision the opportunity to really enjoy his work.

“It is possible to have his work described in a way that brings it to life in an audio form. I think he would have appreciated that.”

Eye of the Storm can be accessed via the Dundee Contemporary Arts home cinema portal

Click here to see the Scottish Gallery’s virtual room of James’s work.