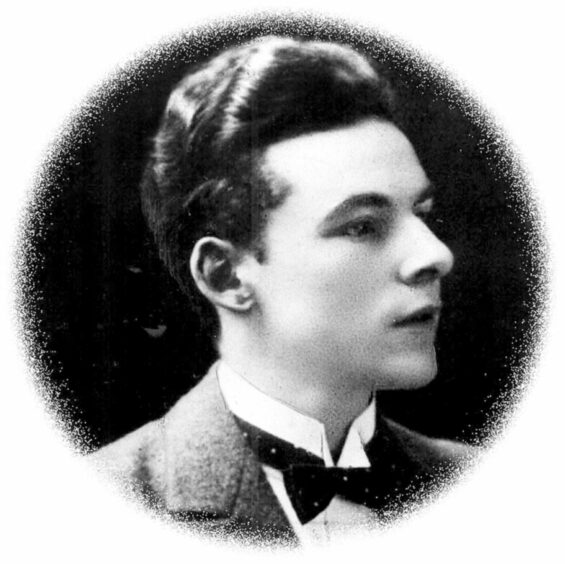

If you’ve ever pointed out a ‘wee Wullie wagtail’ or identified a ‘gowk’ calling ‘cuckoo’ on the hill, then chances are you’ve been parroting the words of Perth poet William Soutar.

But like many Scots, and speakers of Scots, you may not know much about the man himself.

Born in Perth 125 years ago to a master joiner and the daughter of a police sergeant, Soutar suffered the poet’s curse of being unable to commit to any other vocation.

After being demobilised from the Royal Navy in 1919 due to ‘troublesome legs’ – which later turned out to be spondylitis, an inflammation of the spine – Soutar held half-hearted ambitions of studying medicine.

But, a true romantic soul, he changed his mind at the last minute, pursuing a fairly poor degree in English instead.

And when his illness caught up with him so much that he was to be bed-bound within a decade, he took it as a sign to let all his sensible ambitions fall away, writing in his diary: “Now I can be a poet.”

However, despite his dedication, Soutar was not an artist appreciated in his time.

His ‘highfalutin’ writings in English left contemporary readers and critics unimpressed; but his rich Scots verses, particularly his rhymes for bairns, left a faint, yet undeniable impression on the nation’s tongue.

Now as the Scots language undergoes a major cultural renaissance, the high heidyins of literature are re-examining Perth’s overlooked poet.

And since 2013, his family home on the city’s Wilson Street has been reopened to the public on various Doors Open Days by historian Dr Nicky Small.

“Soutar’s ability to reach out to people, to draw them into his world was extraordinary,” she explains.

“While confined to bed for years he was still able to write about life, love, places and nature in both Scots and English.”

And next weekend will see writers, musicians and TV personalities from all over the nation descending on the Fair City for the fourth annual Soutar Festival of Words.

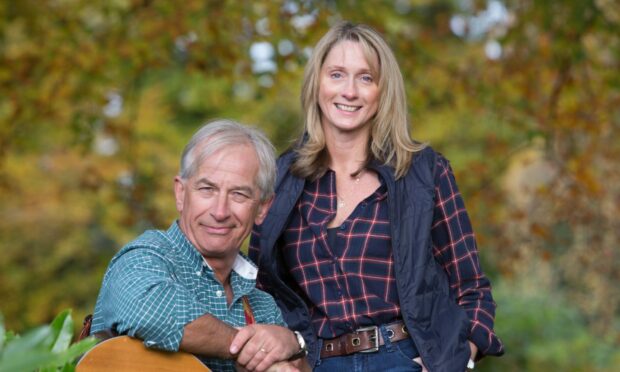

As well as being an expert in Scottish history, Dr Small makes up one half of Perthshire-based trad duo PlaidSong, who will be performing at the festival.

“Soutar’s legacy is something that is rather like the poet himself; almost unobtrusively present in his home town,” she says in anticipation of the event.

“His poems still speak of places we all know and he still lives on Wilson Street, part of the neighbourhood which might not loudly proclaim him but who never forget him.”

And ahead of the festival, I spoke to three featured writers – Alan Warner, James Robertson and Ely Percy – about what it is to be part of Scotland’s ever-changing literary landscape in 2023.

Alan Warner

West coast writer Alan Warner is best known for his 1998 Catholic school novel The Sopranos, which was later adapted into play Our Ladies of Perpetual Succour and, in 2019, hit the silver screen as Our Ladies, featuring Scottish starlet Marli Siu.

However, his latest project – and the one he’ll be bringing to the Soutar Festival – is an entirely different battleground.

Nothing Left To Fear from Hell, part of Polygon’s Darkland Tales series, takes readers inside the head of Charles Edwards Stuart – better known to us now as Bonnie Prince Charlie.

Beginning in the aftermath of the disastrous events at Culloden, and tracing Charles’ flight to across the islands to Skye, the novel is fiction; but the true events at the heart of the story allowed Alan to do what he does best – research.

“I’m staying at the Salutation Hotel when I come to Perth,” says Alan brightly.

“I don’t know if you know, but Bonnie Prince Charlie had his 25th birthday there.

“Though it was all a bit fraught, as you can imagine,” he chuckles. “When you’re on the run with an army, I guess there’s a lot of pressure!”

Alan’s enthusiasm for the everyday details is infectious; legend-level historical figures don’t often get the luxury of things as ordinary as birthday parties, or bathroom breaks, when the ballads are sung.

But it’s those things that he thinks connect the present with the past most viscerally.

“With Bonnie Prince Charlie, we all have these shortbread biscuit tin ideas of him,” he observes. “But when you get down to the nitty gritty of it, you start to get a lot of material from looking at the quotidian.”

Particularly fascinating – and challenging – for Alan was capturing authentic-sounding dialogue when we have no indication of how Bonnie Prince Charlie’s accent or dialect would have sounded.

“The thousands of conversations lost in time, forever,” sighs the 59-year-old author. “What did they look like? What did they sound like? There’s no photos, no recordings. It’s all got to be invention.”

However, one solid fact of the story is the land upon which it took place – a land, Alan points out, that remains largely the same as it was when Charles travelled across it.

“When you go to the parts of the Highlands Bonnie Prince Charlie was in, often there’s no buildings, no high-rises, no motorways. The landscape is pretty much unchanged from 1746, so it’s interesting thinking that what you’re looking at is pretty much what they would’ve looked at.”

Plus, no matter how noble the myth, or how grand the escape, there’s one Scottish curse even Bonnie Prince Charlie was ordinary enough to endure.

“We know the midges drove him mad!” laughs Alan. “There’s plenty mention of them in his letters.

“Though he spelled it ‘mitches’ – maybe that’s how they said it?”

James Robertson

James Robertson grew up surrounded by rhymes about birds and animals; gifted to him in Scots by his granny and his auntie, they live on in muscle memory.

But for the Walter Scott Prize-winning author, Scots is a language of the future, not the past.

And as co-founder of Scots children’s book publishing house Itchy Coo, Angus-based Robertson is putting his money where his mouth is.

In his anticipated Soutar Lecture, he’ll talk about the connection between the Perth poet’s Bairns Rhymes of a century past, and the current Scots stories that Itchy Coo are publishing.

“I want to look at the connections between what he was doing in the 1930s and what we’ve been doing in the last 20 years,” he explains.

“Growing up as he did, as a child in Perth in the early part of the 20th century, his childhood was totally different from the childhood experienced by children in Scotland 100 years later.

“Childhood has changed, and so how have the poems changed, and in what ways do they still say the same things?”

As well as delivering his lecture, James will perform a reading of Julia Donaldson’s The Gruffalo, which was one of the first books Itchy Coo translated into Scots.

It’s important to him that the next generation know there’s nothing low-brow about their native tongue.

“An awful lot of children in Scotland still use a lot of Scots on a daily basis when they’re at home and then they quite often come to school and don’t get exposed to it as much,” he says.

“At that age, around 7-9, children are so open to the possibilities of any language. There’s this whole wealth of literature out there written in the Scots language, and I think they should be able to have access to it.

“And that’s really why we wanted to do the books – to say look, this comes from this country, this is where this language thrived and we should look after it.”

But James, 65, wants children to embrace the language not just because it’s culturally significant – but also because it’s just fun to speak it.

“A lot of Scots words are very onomatopoeic,” he smiles. “If you ask a classroom of kids: ‘What’s the Scots word for a frog or a toad?’ they might not know.

“But as soon as you tell them it’s a ‘puddock’, they get it, because it sounds like the kind of noise that a frog makes!”

Ely Percy

Many writers will claim writing saved their life, but for Ely Percy, it’s true.

The Renfrew native, whose episodic novel Duck Feet was named Scottish Book of the Year 2021, rebuilt their life through creative writing after a traumatic brain injury at 15 left them with no childhood memories and an uncertain future.

Sent to an adolescent psychiatric hospital after their injury “because there was literally nowhere else for me to go”, Ely passed the endless hours by writing letters to friends and, most voraciously, to “Victor Bogoff’s letter’s page” in Big magazine.

“It was the 90s, you didn’t have the internet or a mobile phone,” says Ely frankly. “I was away in this hospital, away from my pals and my family. I had no one to speak to, I was bored out my skull.

“And I was ragin’, because I didn’t want to be there.”

It was one of their “ragin'” letters being selected by Victor that set Ely on the path to publication.

And after finding their own voice, something extraordinary happened – Ely found another voice; that of Kirsty Campbell, the narrator of Duck Feet, all thanks to a writing competition centred on the theme of feet.

“I was sitting in the living room writing down all the types of shoes you can get – brogues, high heels, trainers. And my dad walks in carrying a basin of water for his feet,” recalls Ely.

“And all of a sudden I just heard this voice going ‘My da’s got bad feet’. So I wrote that down, and then I just didn’t stop writing!

“This had never happened to me, beforehand, and it’s never happened again – I just heard this wee girl’s voice, it was like tuning a radio.”

Duck Feet is written in Renfrewshire dialect, but for Ely, the choice to write in Scots wasn’t about making a point about class or culture – it was simply the way her character talked.

“I’d had a shot at writing in Scots before but it didn’t quite flow. But with Duck Feet, it just felt so easy,” they explain. “It was like I was listening to her as she was dictating the story to me.

“I love writing in Scots. I find it much easier. But I think it depends on the narrator.”

When Ely appears at this year’s Soutar Festival, they’ll be interviewed by a panel of LGBTQIA+ youth.

Again, although their books are packed with queer characters, they weren’t never in pursuit of some grand mission of representation.

“When I was writing Duck Feet, it was just writing the people I know,” they say candidly. “I guess over the last nearly 30 years, I have been writing about queer lives, working class lives.”

Although now, Ely admits, they are aware of their power to represent the underrepresented, and strive to use their platform to shine a light on Scottish voices that have gone unheard in literary spaces.

“I said about two years ago that I was going to make more of an effort to write about neurodivergent and disabled characters,” they explain.

“And let’s face it, they’ll probably be queer!”

The Soutar Festival of Words 2023 will take place at various venues in Perth from April 28-30. For more information and to book tickets, see the festival’s website.

Conversation