Two hundred years after the last armed uprising in Scotland which followed Manchester’s Peterloo massacre, Michael Alexander discovers the key role played by Dundee in sowing the seeds of political and social reform that swept Britain.

When a series of dramatic events exploded around Glasgow, central Scotland and Ayrshire during the first week of April 1820, revolution was in the air.

Just months after Manchester’s Peterloo massacre when drunken yeomanry infamously rode into a peaceful crowd killing 15 people and wounding hundreds more, 60,000 Scottish weavers and other workers went on strike demanding similar political reform and better living and working conditions.

It was the culmination of several years of unrest, which had seen huge mass meetings in Glasgow and Paisley.

In April 1820, some Scottish Radicals marched under a flag emblazoned with the words ‘Scotland Free, or Scotland a Desart’ [sic].

Others armed themselves and set off for the Carron Ironworks, seeking cannons. Intercepted by Government soldiers, a bloody skirmish took place at Bonnymuir near Falkirk. A curfew was imposed on Glasgow and Paisley.

Aiming to free Radical prisoners, a crowd in Greenock was attacked by the Port Glasgow militia. Among the dead and wounded were a 65-year-old woman and a young boy.

In the recriminations that followed, three men were hanged and 19 were transported to Australia from Scotland.

But while much of the events 200 years ago this week was centred upon Glasgow and the Central Belt, aggrieved workers in Dundee were very much behind the demands for reform.

Author Maggie Craig, 68, who grew up in Glasgow, is no stranger to writing about history.

But the now Huntly-based writer admits that when she came to research her new book , it was a learning curve about a chapter in history she feels many Scots know very little about.

“What happened in Scotland was all part of the same unrest that happened at Peterloo in August 1819,” said the former translator and Scottish tour guide, who grew up listening to stories about the Red Clydesiders from her Labour councillor father.

“After the Napoleonic Wars there was an economic downturn and soldiers were flooding home – there weren’t enough jobs to go round and people were very poor.

“Parliament was very corrupt and only a few people were elected MPs. So people were pretty desperate and they wanted a radical reform, which is why they were called Radicals.

“You can draw comparisons with the unrest after the First World War – Bloody Friday in George Square. People think that might be when Scotland came close to revolution. But I think it was 1820.”

Maggie said the conditions for working class Dundonians including weavers were very similar to Glasgow and other industrial heartlands at the time.

Agitation had been brewing in the city since 1789 when the French Revolution began influencing Scots with its ideas of liberty, equality and fraternity.

Inspired by the French and the American Revolution before it, a group of Dundonians planted an ash sapling ‘liberty tree’ at the town cross in 1793. They decorated it with ribbons, oranges, rolls and biscuits. Then they lit a bonfire and set off fireworks.

Everyone got drunk and the story goes that when they were sleeping it off, Dundee’s Tory Lord Provost Riddoch had the tree dug up and allegedly “threw it into jail, thus achieving history as the only civic head in the world to have jailed a tree”.

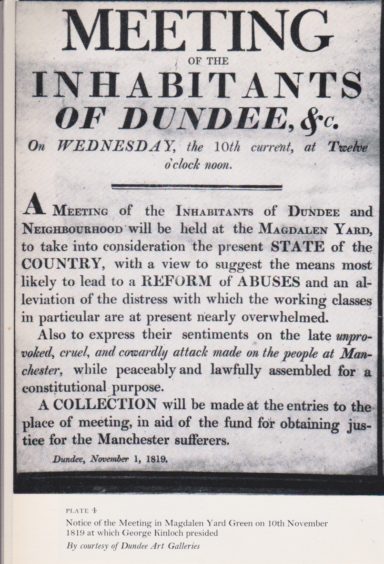

But Maggie said the revolutionary undercurrents really came to a head again in the wake of the Peterloo massacre when a pro-reform meeting was held in Dundee on November 1, 1819.

An estimated 10,000 people came to the open space of the Magdalen Yard Green to show solidarity with Manchester. The chairman of the meeting was future Dundee MP George Kinloch of Kinloch. He was a local laird and landowner, instrumental in the development of the harbour at Dundee, and very much in favour of parliamentary reform.

“The working people of Dundee collected £16 for Manchester – a sum to which George Kinloch added £10,” said Maggie.

“Concerned that the meeting should pass off peacefully, he had asked people not to bring flags and banners. Some did all the same. They carried various slogans. ‘We only want our rights in a peaceable and constitutional manner. For the sufferers at Manchester. The voice of the People is irresistible.’

“Other people carried poles from which hung broken tea pots, pieces of broken wine glasses, pipes and snuff boxes.

“They symbolised habits which some radicals believed should be rejected, both because the government taxed such products and also because the people should demonstrate they were not in thrall to such bad habits.”

Kinloch warned the crowd to be on their guard against government spies and reiterated calls for universal suffrage – at least male suffrage – annual parliaments and secret ballots.

He was arrested on a charge of sedition two weeks later and, after escaping from Edinburgh and spending time as an outlaw in France, was granted a pardon in 1822.

Ten years later Kinloch became MP for Dundee in the first parliament elected after the Great Reform Act. He died just months later and is commemorated with a statue in Dundee’s Reform Street to this day.

Maggie said it’s clear the government got a “hell of a fright” in 1820 – especially as the strike was called by a “provisional government”.

She feels that’s probably why the chapter in Scottish history has largely been “swept under the carpet” since.

*One Week In April: The Scottish Radical Rising of 1820 by Maggie Craig is out now.