With plenty of time on his hands during the coronavirus lockdown, Murray Chalmers turns to his cookery books, a treasured collection gathered over a lifetime.

I have such a vast collection of cookbooks that I could open a shop and in happier times, should we ever again justify the odd frivolous purchase as essential, I will seriously consider it.

My shop will be called Gorgeous Things and will be full of stuff you don’t really need but might just WANT. Everyone who comes in will get a hug. You will be forced to stand as close to other customers as possible, hopefully without infringing any basic human rights or laws of decency. Wine will not just be offered but your agreement to vast consumption of it will be a condition of entry. Olfactory joy will be pumped into the air via a selection of vastly expensive scented candles, reminding us of the transience of existence and, on a more basic level, how Jo Malone keep discontinuing their best smells.

Northern Soul and Motown blasting out the speakers will lead to such frenzied dancing that we will have to throw the doors open and move out onto the streets. No lockdowns EVER!!

Naturally cookbooks will play a large part here, although many people were already starting to consider them unnecessary in the digital age.

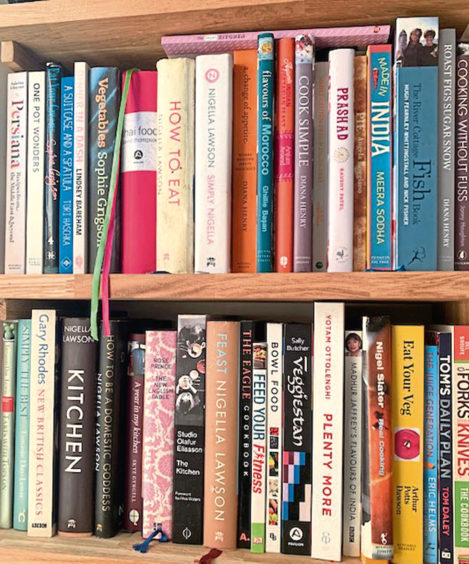

I have hundreds of the beauties and even after having special shelving made in my utility room and kitchen, many still reside in the cardboard box graveyard that is my spare bedroom.

Added to this I have a considerable library of British cookbooks in the house I co-own in France, mainly because my French isn’t good enough to use local books. My collection comes from various sources – new, old, borrowed but never sold – and together they represent a very considerable chunk of my adult life.

Confession time

However I am the least likely person to alphabeticise anything, so finding a book isn’t always so easy; confession time – sometimes I’ve had to go a bit Elton John extravagant and have two copies of the same book, albeit often in different editions.

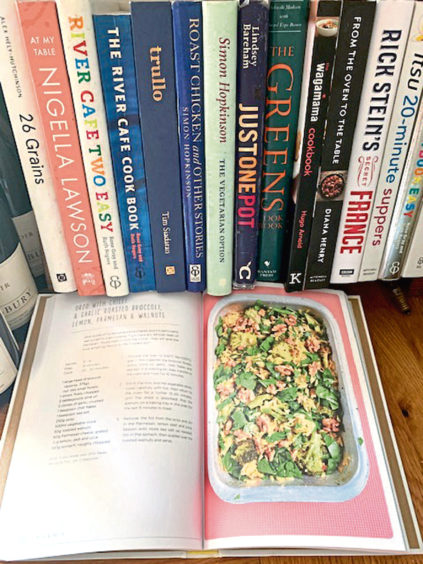

My rule/moral trade-off for this excess is that the second copy always has to come from a charity shop. So, for instance my first edition of the classic blue River Café cookbook was bought at full price at the terrifically niche Books for Cooks in London’s Notting Hill, whilst my later paperback edition was bought for 50p in a charity shop at the bottom of Leith Walk.

I’ve noticed recently that many people who had renounced cookbooks in favour of online recipes have rediscovered the joy of the physical page. I’m sure minds cleverer than mine could write theses on our responses to self-isolation/confinement but, with our monthly spend on groceries recently eclipsing even our food spend at Christmas, it’s clear that bountiful-batch home cooking has become something many of us have chosen as a way to fill the days. I’ve got a pile of books at both sides of my bed – fiction, biographies, art books mainly – and yet increasingly the books I turn to before the light goes off are old cookbooks from the 30s and 50s, times that obviously had their share of turbulence but on which nostalgia has painted a rosier hue.

A straw poll of friends online has confirmed that cookery books are having a revival. There’s a very practical reason for this; when your phone screen goes blank and you’re in the middle of making banana bread, you need to touch it quite a few times to bring the recipe back. Your screen gets covered in food and, unless you remember to clean it regularly it can only be a matter of time before the listeria moves in and claims squatters rights. Some things are ok for a revival in my book – stuff like old school house music, the artier side of Britpop, Creamola Foam and Stanley Baxter TV shows – but we don’t need to revive any more nasty diseases to remind us how vulnerable we are.

With a cookery book you find your page and you follow it. You don’t need to swipe for ingredients and you don’t need to expand the wonderful accompanying photos. You open it, you turn on Radio 4 and you get cooking.

Premier league cookbooks

In my kitchen I have a beautiful small book trough carved by the iconic Yorkshire craftsman Robert Mouseman. Within that trough are a selection of the 15 cookbooks that I reach for most often. They are the premier league, the last gang in town, the conduits to supper being served in this house. To me they are indispensable.

Three at this top table are by Simon Hopkinson, including his iconic Roast Chicken and Other Stories (1994). I love the way Hopkinson writes – a perfect mixture of supreme knowledge, wit, waspishness and wonder. He does it properly and he makes you want to do the same; in fact he doesn’t really countenance any other way. To read one of his books is to bask in the words of a man at the absolute top of his game. I think most underrated of his books is The Vegetarian Option (2009), not least because chefs of this calibre often have a problem with vegetarian food. This book has so many amazing recipes including a brilliant Chilli con Carnevale and a recipe for boiled onions with poached egg and Lancashire cheese that is life-affirmingly good. Top stuff!

I also have three River Café books within reach, the best being the classic debut game-changing tome which famously stated that Rose Gray and Ruth Rogers were returning a lot of Italian family recipes from their restaurant to the domestic kitchen.

I’m a sucker for the River Café which, in former years, was always my treat place in London. The food here somehow tastes even more of itself than you’d think possible and although the restaurant prices are very high (like Mary Quant hemlines they started high and went higher) with this book and a few good suppliers you can cook a mean Ossobuco in Bianco with gremolata and Risotto Milanese that will transport you to the Italy we all loved to visit in happier times, albeit via Hammersmith in London.

Vegetarian delight

Next up is The Greens Cookbook (1987), another classic, although this time from San Francisco. Throughout much of the 1980s I was vegetarian, and not just because of The Smiths’ Meat is Murder. But, at a time when many people were turning to vegetarianism, the standard of food just wasn’t great. Books like this were a godsend if you got sick of the Cranks school of crocheted lentil burgers (I loved Cranks but sometimes the lack of variety made you feel a bit war-torn without there being an actual war).

Greens was different. It was vibrant and new and fresh – and sometimes bloody complicated to make! It relied on things we didn’t really have here at the time – farmers markets, beetroot that wasn’t pickled in a jar, and an exotic thing called arugula which at that point was far from ubiquitous (of course we can get it in the Co-op for £1 now). Greens’ food largely required lots of cooking and often before the cooking there would be hellish pre-soaking of pulses. I remember spending two days creating a feast from this book only for a snooty friend of mine to push it around her plate with the comment “Eugh, this is positively VEGAN!”, a remark that was anything but positive that night or any other for a good few decades. I remember when I finally got to San Francisco and ate at Greens I thought there should be a plaque on the wall celebrating all they had done.

Greatest love

Now comes the book that I use most of all, so much that it’s starting to fall apart. For eight years Lindsey Bareham wrote a brilliant daily after-work recipe for the Evening Standard and then The Times. She has published many excellent books and co-authored Roast Chicken and Other Stories and The Prawn Cocktail Years (2006) with Simon Hopkinson.

But, for me, her best book is Just One Pot (2004) which was written while she was having a new kitchen installed and only had one cookery ring at her disposal. This is the equivalent of her after-work columns; the book is full of great things to eat but most of them with ingredients you could get from the corner shop.

In its way the cooking is just as rigorous as Simon Hopkinson but with more allowances for the pace of modern life, and less reproach for shortcuts. The page with the recipe for jambalaya is so food-stained that it can’t be opened but I’ve cooked this failsafe dish so many times I could make it in my sleep. This is the book for all those times you think you can’t be bothered and, in a way, there is no higher praise than that.

Last but not least

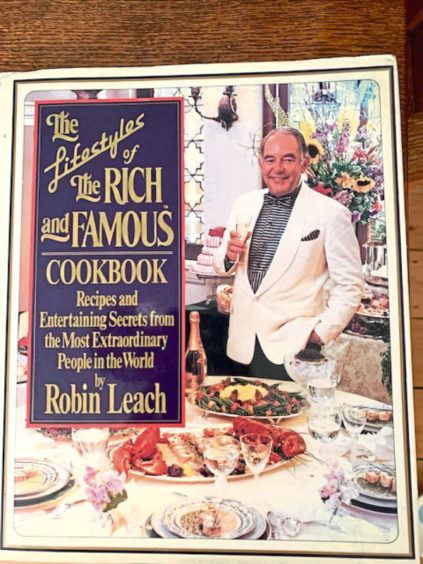

The last book isn’t on any shelf of mine but I discovered it at the bottom of a box with a whole load of old cables and leads – yes it was deemed THAT crucial to my life. However I have to say that in these dark days The Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous cookbook has brightened the hours in a way that only The Windsors on TV can, and for much the same reasons. Princess Michael’s priceless quote about us civilians is worth the price of admission alone.

“The people of New Orleans may well tell their children one day of the time they met a real Princess and Prince” she beams, talking about a lavish fundraising charity ball she attended. “I want to let in a little chink of light, a little compassion wherever I can”. Who said the rich have no compassion?!

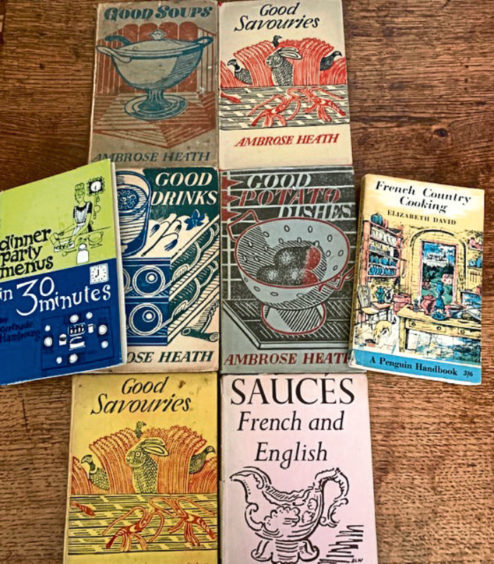

My second tip re cookery books is a bit more egalitarian; try to search out the beauties written by Ambrose Heath in the 1930s and published by Faber. Although uncredited in some volumes they feature the most wonderful “decorations” by Edward Bawden. I picked them up years ago for £3 each and they are beautiful little works of art. Have I cooked from them? Are you mad?!