Now that we’ve all had a few weeks of lockdown – a unique and unprecedented time of our lives – we’ve had time to get to grips with the social isolation that being stuck at home pretty much 24/7 brings.

But before you complain, spare a thought for the folk whose everyday job means they barely ever see another soul, sometimes for days on end.

Imagine, for example, being marooned in a lighthouse for weeks on end, with only the crashing of the waves and the cry of the gulls for company.

The Bell Rock lighthouse, 12 miles off the coast of Arbroath on the deadly Inchcape Reef, was a manned light for 177 years until 1988 when the last principal keeper, John Boath, retired.

Referred to as a “temporary Alcatraz” by author Michael Strachan in his book Bell Rock Lighthouse, it was a lonely and exiled existence for the keeper.

Tom Nancollas, the author of Seashaken Houses: A Lighthouse History from Eddystone to Fastnet, reveals a fascinating fact about the Bell Rock lighthouse: “It once housed the only Georgian library ever built in the North Sea, in the uppermost room of the tower, which had exquisite cabinetry, ornamentation and a domed ceiling,” he says.

“Famous poets of the day would visit and sign the visitors’ book. Sadly, this remarkable interior was lost in a later refurbishment scheme.”

Books were something of a necessity for John Boath, the last principal lighthouse keeper on the Bell Rock, as he was posted there for three or four weeks at a time.

Now in his 80s, John admits it was the last posting any keeper wanted during their service.

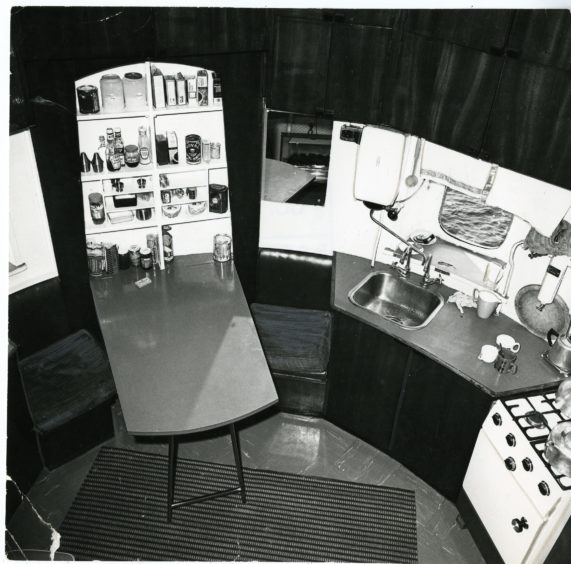

“It was like living on a vertical submarine and very basic inside as there was heating and no shower,” he recalls. “The toilet flushed with sea water pumped up to the header tank and at one stage the system broke.

“I had a single-bar electric fire to keep me warm and any power was used for navigation light, beacons, VHF and radio signals. It was quite cosy when I was tucked up in bed – it had stood there for nearly 200 years so I wasn’t worried it was going to fall apart!

“Bell Rock was the first lighthouse to have a TV but I didn’t watch it much. I used to read a lot and I was always in the workshop painting or making wee models and toys for my boys. I missed the family but I tended to close my mind to it.”

And if he was on the lighthouse at Christmas he made sure he marked the occasion.

“Once I was away for four Christmases on the trot but I put up a tree, and I was sent a cake and the usual festive cheer in the form of bottles – although I made sure I rationed them!” he says.

Switching off Bell Rock in 1988 was a moving moment for John. “I was sorry to leave but I have my memories.”

John’s memories reveal that solitude isn’t necessarily a bad thing and Professor Ewan Gillon, clinical director of First Psychology Scotland, explains why some people are drawn to isolation: “People are very different, and some of us simply prefer a quieter life,” he continues.

“Isolation can give us time and space, which can help us become more grounded and relaxed in our own lives. It can help us feel more connected to the natural world around us, as we are able to focus on this without distraction.”

But as Prof Gillon points out, isolation can become a problem.

“We can become lonely and lose perspective which can be distressing and make it hard for us to maintain relationships,” he says.

“Having a routine and structure is an important part of coping in isolation, as this will become familiar to us and generate a sense of safety and stability. This routine should include things that keep as well such as exercise, healthy eating and, of course, keeping in contact with other people even if this is online or by phone.”

Fife farmer and bestselling author James Oswald admits that he’s always been happiest keeping his own company.

“As a child I would more likely be in my room with my nose in a book than out playing with my two brothers and sister,” recalls James, who has penned the Inspector McLean series of Edinburgh-based detective novels, Constance Fairchild novels and the epic fantasy series The Ballad of Sir Benfro.

“We all grew up in a house out in the countryside, and were encouraged to entertain ourselves as much as possible. I’ve never really taken to city life, although I spent the best part of 10 years living in Aberdeen, and another five in Roslin and Edinburgh. I’ve worked in retail and in call centres, so face to face or on the phone all day long interacting with other people,” he continues.

“It would be wrong to say I hated every minute of it, but not far wrong. Time spent in my own head, either at the keyboard or the wheel of the tractor, is much preferable to time spent dealing with people.

“The frustration comes when I do have to deal with people. Usually this is in the form of my noticing that something is broken, needing a part to fix it, and only then realising it’s the weekend and the agricultural merchants are closed. Likewise I find Christmas a very stressful period, but for the exact opposite reason most people do.

Currently working on the eleventh Inspector McLean book, he reveals: “At this stage of the process it’s all about getting words on the page, so regardless of the situation in the outside world, I would be a bit of a recluse right now. I try to write between 1500 and 2000 words a day, seven days a week, mostly in the evenings once the farming is done.”

James is a livestock farmer, running a pedigree fold of Highland cattle over some 350 acres of north east Fife hill land, and time never hangs heavy on his hands.

“The cows will begin calving in mid-May, so at the moment they only require feeding and checking every day,” he says.

“Last year’s calves were weaned a few weeks ago, and are currently in the cattle shed.

“Everyone else is out in the fields eating grass. I am very pleased that it’s finally stopped raining for a while – parts of the farm were beginning to look like quagmires, and I’m fairly sure some of the cows have developed gills.

In the next fortnight or so the pregnant cows will be moved onto the better pasture to get them ready for calving.

“And then there are endless other maintenance jobs that need doing on the farm whenever time and weather permit.”

But he admits that spending too much time on one’s own has the potential to also allow negative thoughts to fester and grow.

“Without other people to interact with and measure your experience against, it can be all too easy to develop a feeling that you are alone and nobody is going to help,” he says.

“Farmers are a hardy lot, but often unwilling to concede defeat, admit weakness or seek help, which coupled with the often isolated nature of the job is why farming has one of the highest suicide rates of any occupation in the UK. Isolation can be a great escape from the pressures of modern life, but it can also become an intolerable pressure in its own right.”

Nonetheless happy in his own company, he reveals that it’s not isolation that’s the problem: “Mostly I need coping strategies for when people come to visit, or when I have to go out into the wide world and interact.

“I love meeting people when I do library events or at literary festivals, but the build up to them is excruciating, and I’m usually exhausted for a week or so afterwards. Working in isolation is my coping strategy!

“And you’re never alone if you’ve got a book to read.

“A well-written book encourages the reader to construct worlds and build the characters in their head. It doesn’t matter whether it’s fiction or not, and audiobooks are totally reading! I listen to audiobooks while I’m out and about on the farm, which in many ways means I’m not isolated at all.”

Spending time on his own in the countryside is something Sam Docherty thrives on. A woodland ranger for Falkland Estate, who leads lead conservation projects and outdoor education, and helps with woodland management and path maintenance, he spends days at a time on his own.

“I love being away from other people in the countryside – I suppose I chose this line of work to get away from busy towns, factory work and polluted city air,” he reveals.

“You get a great sense of space and self-dependence when you live and work in more isolated locations. The pace of your life and work can be more connected to natural rhythms such as seasons and weather, rather than clocking in on time and beating the rush hour traffic.

“People who choose to work in more isolated jobs are probably very happy with their own company and like to be organised without too many distractions. And isolated jobs are generally done by people with a sense of responsibility, they care about what they are doing and want to enjoy getting on with it,” he continues.

“I never feel isolated because I have a mobile phone. There is never an hour it doesn’t ring or a message about another task somewhere on the estate.

“But I think being able to spend time alone is a very beneficial to your mental state. It can give you time to think things out, put problems into perspective, and plan for the future. Or just read those books and do those paintings you had always wanted to get around to. And long periods of social isolation can make you really appreciate company when you do get to see people too.

“I’m not just wandering around feeling lonely – I have a place to get to, get a task done, and move to the next task. And I enjoy it. I get to see lots of beautiful sights every day.

“I spend many days alone routinely, and I fill my spare time with my many hobbies, music, gardening, woodwork, art, games, movies, books, homebrewing, so much to do and so many ways to entertain myself,” he smiles.

Although dairy farmer Ross Logan lives on the family farm in Stirlingshire with his parents, wife and children for company, he often spends hours each day on his own in the tractor once the cows have been attended to.

“I enjoy my time in the tractor – it gives me the opportunity and space to think about things, which can be good or a bad thing!” he says.

“It gives me a chance to catch up on the phone with people on the phone.

““I guess there are people drawn to isolation but I don’t think I would like spending lots more time on my own. I’m lucky that my job means I am out in the fresh air and can break up my day talking to the cows and my family. The cows are great listeners and they don’t talk back!” he chuckles.

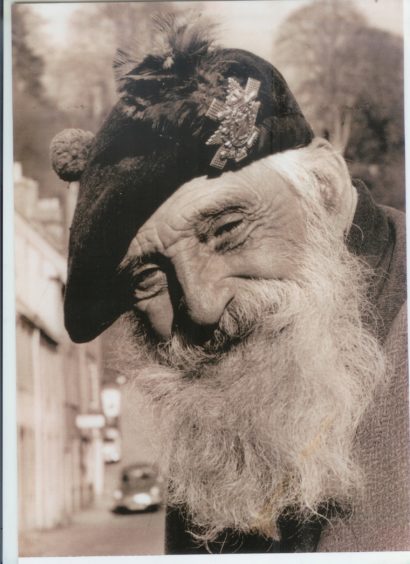

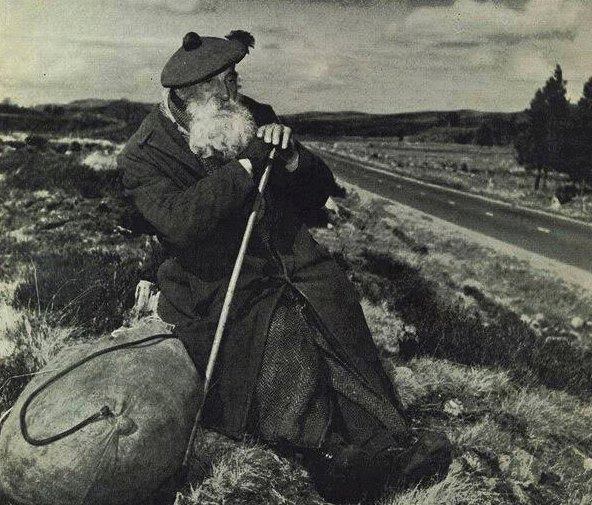

Scottish Traveller, author and storyteller Jess Smith recalls a Traveller who deliberately sought solitude and isolation – tramp man Sandy Stewart.

“With his flowing white beard, his Black Watch bunnet and heavy army coat, Sandy was every inch a ‘free man,’ says Jess.

“He had no address, no regular contacts, and seldom spent time in conversation apart from a wave of the hand to whoever should acknowledge his presence.

“He certainly didn’t tolerate strangers and, with his ever-ready cromack to hand, held them suspiciously at length. I suppose, given the coronavirus, the two-metre stand could have applied to Sandy.

“Another lone fox I remember had no name but was known as the Tinsmith. I loved him for his mystery – he could transport you in his old tales of the Fairy folk but seldom spoke apart from ‘go and find a wee drappy tin cans for me lassie.’ He paid me two pennies regardless of how many I presented him with.

“He had a small mobile forge and all his usual tools. You could see him clanking away doing his job, no government interference, no bank account, no roof above his head. Most important was his ‘oneness’ – his lonely existence seemed to suit him down to a T.

“He offered a day of rummaging in grass verges, raking middens, beach combing, running along railway banks searching for the important tin.

“My maternal granddad ended his days as a lone tramp of the roads; he was a cobbler and kept his tools in a brown leather doctor’s bag.

“Tramp men of my youth cherished freedom more than anything and I wonder how they would have fitted into today’s world within a pandemic prison. People desperate to reach out to others, offering help but restricted on all fronts. “There must be many like my loners, whose very existence depends on an outside living. I wonder what their thoughts are regards the future?

“My most powerful vision is sitting as a lass, with Tinsmith hammering away and speaking, not to me but to the Fairy folk who cannot be chained in the memory of a child and remain free.”