It’s many people’s dream job but few are successful at it. Jack McKeown swots up on how to become a writer

Stephen King famously gave up on writing after hundreds of rejections, only for his wife Tabitha to pull the pages of Carrie out of the bin and force him to complete it.

After writing her first novel in an Edinburgh cafe, unemployed single mother Joanne Rowling’s manuscript was rejected by 12 publishers before Bloomsbury finally gave Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone the green light.

Brandon Sanderson got a job as a hotel night clerk because his bosses didn’t care if he wrote books at work as long as he was awake. He completed a dozen novels before getting his first published and has gone on to become one of the best-selling fantasy writers of all time.

Becoming a writer isn’t easy, and even the biggest names in the industry needed tenacity and a dollop of luck to get started.

Thomasin Collins is a student of English and creative writing at Dundee University. About to go into her fourth year, she was recently awarded the PNR Prize for Creative Essaying at the university, handed out by the literary journal of the same name.

The 21-year old from Nairn won the award on the strength of her year’s essays, particularly a work called Secrets Found in the Deep. The essay describes how she falls into a reverie while viewing a painting by Scots artist Will Maclean, thinking of her mother’s gallery in Inverness and of the Iolaire, one of Scotland’s most tragic 20th Century naval disasters – the centenary of which was commemorated last year by the unveiling of a sculpture by Maclean.

“My mother has Will Maclean’s paintings in her gallery and I’ve always really liked his work,” Thomasin says. “It was around the time of the disaster’s centenary when we visited the McManus and something about that and the power of his work really affected me.”

One of Thomasin’s teachers is Dr Gail Low. The senior lecturer in English is one of the teachers on Dundee University’s creative writing degree course, along with professor Kirsty Gunn.

The course has been running for nearly 15 years and takes in more than 100 new students every year.

It offers everything from modules to degree and post-graduate qualifications and Dr Low says it’s had numerous successes over its time.

“We’ve had quite a lot of people go on to be published, whether it be poetry, criticism or prose,” she says.

“Notably, we had Sandra Ireland on our course, who has gone on to publish thrillers and enjoy commercial success.”

When it comes to how to become a better writer both Dr Low and Prof Gunn have the same piece of advice.

Gunn says: “To be a writer you need to be a reader. Reading teaches you how to write. If you’re not devoted to reading you’ll find it difficult to become a writer.”

Hamzah Hussain is another former student to have benefited from the university’s creative writing courses. The 26-year-old studied English literature and creative writing and then took a postgraduate masters in creative writing. After work experience with The Courier and Dundee Rep he was taken on for a one-year traineeship with publishing giant Hachette.

“The MLitt at Dundee had a couple of publishing modules and I enjoyed them,” Hamzah explains. “Working at Hachette I’ve loved seeing how books go from the manuscript through the editing and print process until they’re on the page.

“I really have fallen in love with publishing, though. Eventually I would love to become a senior commissioning editor with my own stable of writers.”

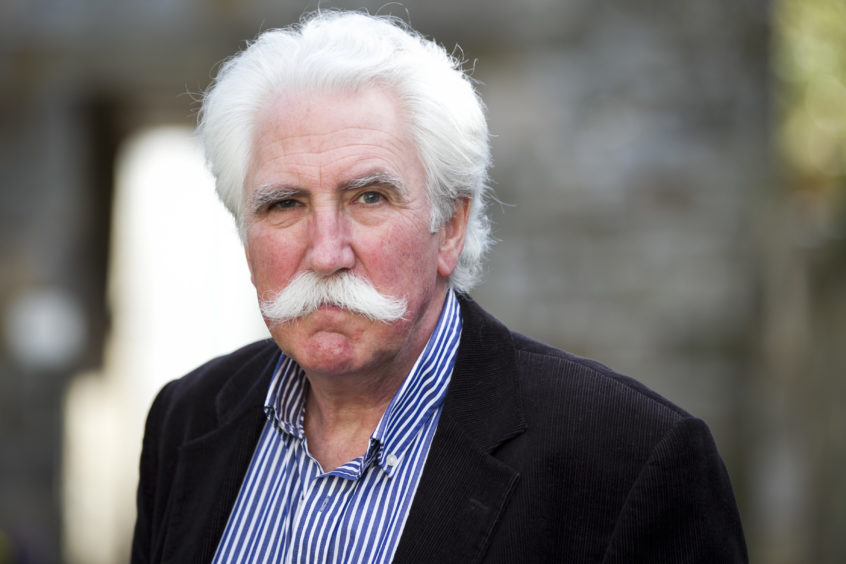

Brian Johnstone co-founded St Andrews poetry festival StAnza and was director from 2000-2010. The 69-year-old poet lives in Fife. After having some of his poetry published as a student in the late 1960s, he then settled into a teaching career before deciding to give writing another go in the mid-1980s.

“At that time my employer, Fife Council, allowed you to take up to two years off as a sabbatical and would hold your job open for you,” Brian says. “That gave me the opportunity to try my hand at writing but with a job to fall back on if it all went wrong.”

One of Brian’s most recent works, Double Exposure, is a book about his childhood, his parents, and a startling discovery after their death. It’s a work of prose but the vast majority of Brian’s writing is poetry.

“Poetry is very difficult to make a living at,” Brian explains. “Unless you’re a Seamus Heaney or a Roger McGough you’re not going to make a lot of money at it. Most poets, even very big names, supplement their income with teaching or something else.

“In my case I was fortunate enough to make a bit of money from poetry and also got work at the university teaching creative writing.”

Brian thinks there’s never been a better time to become a writer.

“When I attended my first poetry events in the 1960s and 70s it was almost exclusively older white males that dominated the scene. There’s still more improvements to be made, of course, but now it’s much more diverse.”

Does he have any advice for people who want to make a living from writing? “Publish, publish, publish. It’s never been easier to do it. All the magazines and other publishers are at the end of a Google search. Send your work to as many places as possible, get as much published as you can.”

Earlier this year Fife-based playwright and poet Rebecca Sharp won an award from the Royal Society of Literature. The £3,000 prize money will allow her to complete a poetry pamphlet called Rough Currency, about oil and fossil fuels.

Rebecca, 40, lives in north Fife and has worked as a writer since 2001. Her first play was staged at the Arches, the famous Glasgow arts venue.

“It’s definitely not like a normal job,” she says. “You don’t have a pay cheque every month or the same security. I live in a lovely spot out in the woods but I rent my house – I’ll never be able to afford to buy.

“That said, it’s a lovely way to earn a living.”

Sara Hunt runs publishing firm Saraband, which publishes numerous books by Scottish authors, including former Courier columnist Jim Crumley. She says the book market is tougher than it once was but that shouldn’t put people off.

“Discounting changed things,” she explains. “For decades the Net Book Agreement meant every book in Britain had to be sold at the price displayed on its cover. When that was abolished in the 1990s supermarket and online retailers started heavily discounting.

“This changed the book market. Instead of printing a huge range of titles publishers would pick a few books by authors with proven track records and market them hard. Only a handful of new authors who wrote really well and fitted into a trend were able to make a breakthrough.”

That may sound depressing but Sara also has positive news. “Non-fiction is much easier to get published. If you have an area of expertise there’s a ready-made audience out there for you.”